(RNS) — Holocaust survivors are generally valorized for their courage and held up as exemplars of endurance and grit in the face of unimaginable pain, suffering and loss. Less understood — especially as those survivors die off — are the ways their trauma has reverberated onto their children.

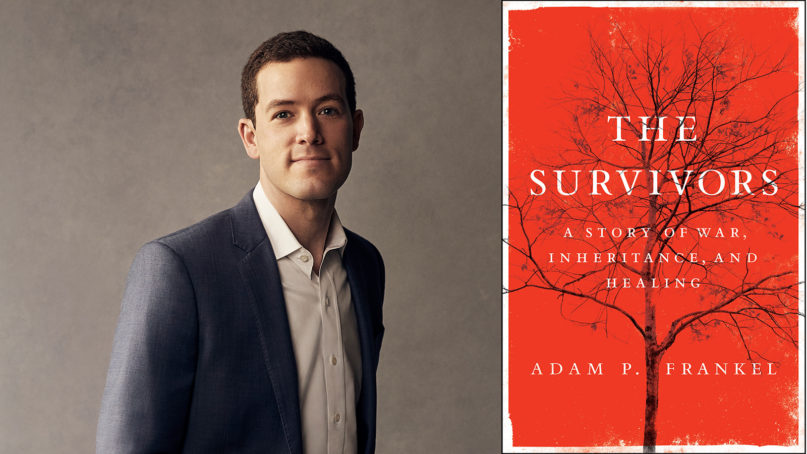

Adam Frankel’s new book “The Survivors: A Story of War, Inheritance and Healing,” explores some of those psychic wounds as they played out in his own personal history.

A former speechwriter for Barack Obama, Frankel was known in the Obama administration for writing stirring eulogies. And in “The Survivors,” he has written a heart-wrenching memoir in clear, succinct prose.

The book also offers a peek at two starkly different American Jewish experiences.

Frankel’s maternal grandfather, a watchmaker, survived the Dachau concentration camp as a forced laborer for the Reich’s wartime construction projects, which included building massive underground bunkers for military aircraft. His maternal grandmother spent the war hiding in the forests of Lithuania. Many of their family members died.

When the war ended, the two met in a displaced persons camp in Germany, married, and in 1950 set off for New Haven, Connecticut. There, they started life anew, opened a small jewelry and watch repair shop and raised four children. The second, Ellen, is Frankel’s mother, whom he describes as mentally unstable, depressed and possibly suffering from borderline personality disorder.

Frankel suggests his mother’s troubles may be partly due to growing up in a family of Holocaust survivors and learning coping strategies from them that, while useful in a time of war, may be emotionally damaging during peacetime.

In contrast, Frankel’s father and his parents, all U.S. born, were the picture of American Jewish wholesomeness: successful, civic-minded, loving and generous. His paternal grandfather fought in the Pacific during the war and later became a speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy, George McGovern and Adlai Stevenson.

Frankel, whose parents divorced when he was 5, loved both sets of grandparents but saw his paternal grandfather as his polestar.

The story might have ended there, except that at the age of 25 — spoiler alert — Frankel found out his mother had a long-term affair during her marriage and that he is not his father’s biological son.

The news plunged Frankel into an existential identity crisis for which this book is part examination, part therapy.

Along with his job — he is senior adviser at the Emerson Collective, a social change organization, as well as at Fenway Strategies, a communication firm founded by Obama’s former speechwriters — Frankel has worked to confront the secrets of his past, forgive his mother and move on.

In the book, he tells his wife, “The trauma stops with me.” But he adds, “It was as much conviction as prayer.”

Religion News Service spoke to Frankel, now 38 and living in New York City, about family trauma, his identity crisis and writing as therapy. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

Did writing the book help you resolve your identity crisis?

Writing the book was not the only part of my journey but it was a major part of it. I certainly do feel better and more grounded. For the first time in my life, frankly, I know who I am in a very real way. My core identity was shaken and there was such a jumble of information and emotions that I was unable to process. Writing the book helped me process it. There’s a lot of pretty rigorous and widely accepted research on the benefits of expressive writing pioneered by James Pennebaker at the University of Texas at Austin about the way writing about feelings and thoughts weighing on us can have physical health benefits. I’ve certainly found that to be the case.

Are you convinced that science has proved the intergenerational transmission of trauma?

I’m convinced that trauma can reverberate across generations. There is evidence of epigenetic impact of trauma from one generation to the next, but we don’t know how it’s transmitted. We know children of Holocaust survivors may be more likely to develop mental health issues based on the ways their parents responded to their Holocaust experiences. But the science doesn’t bear out that trauma can be directly inherited from one generation to the next.

You write about your mother’s family’s penchant for secrets. Was it a survival mechanism learned during the Holocaust or just a cultural habit?

It’s not just our Jewish families that have a penchant for secrets. But I do believe the Holocaust experience deepened the commitment to secrets and the culture of secrecy. It was a survival skill. In our family, there were lessons about not trusting anyone outside your immediate family, not even cousins. You could really only trust your parents or your siblings. One of the larger themes I observed in my family is the way these survival skills my grandparents deployed so effectively during the war to make it through each day became problematic in a different, newer, peaceful, safe setting of the United States.

In conversations with my mother, she acknowledged that it predisposed her and made her feel comfortable with secrets and it probably made it that much more familiar — the process of keeping the secret of my own identity.

What other coping mechanisms became problematic in the U.S.?

In the camps, any display of weakness was to be avoided at all costs. Survival depended on strength and projecting strength in every moment. One of the harmful ways that was manifested after the war in the United States was the denial and stigma surrounding my mother’s depression and mental health issues and an unwillingness to talk about it or grapple with it openly. That sort of stigma is common in many other families as well and many other contexts. But in our family that contributed to it.

It’s ironic that your dad and his family, to whom you are not biologically related, ultimately shaped you, perhaps as much as your mother and her family. Are you a test case for nurture over nature?

I do think I benefited immensely from being raised by the Frankel family, which I consider my family. I feel that very profoundly and I feel their love to this day. I believe they knew I was not their biological grandson but it didn’t make any difference to them. One of the larger lessons, as I began to piece the story together, is that families really are built on love and not biology.

Would you describe your journey in a spiritual way?

A spiritual quest is about understanding who we are and our place here and trying to find our way through some of those big questions. Going back through my family’s history has deepened my awe for my grandparents and has given me a broader, more complex understanding of their experience. It has also deepened my awe for them for what they endured, purely on account of their faith and what all of us in my family owe to them and the obligation that falls on each of us to uphold that heritage going forward.

Are you part of any survivors network or support groups?

Years ago in D.C., I attended a third-generation Holocaust survivor network. My hope in writing the book is that if we can understand the ways trauma reverberates across the generations, it can help us move forward. It’s an experience we all share. At a time when we’re made to feel apart from one another and divided by faith or ethnicity or any number of other things, understanding that common link is one way of seeing ourselves in one another. I think that’s important.