(RNS) — Sylvia Weinstein, a 70-year-old Jewish woman from the Bronx, hears that there is a guru in the Himalayas who has unique access to the Truth.

She books a flight to India, then takes a train, and then a bus, then hires a few sherpas to carry her up a mountain. She gets to the summit and makes her way to a cave.

There, she encounters the guru. He is sitting in a long white robe, with long hair and a beard, fervently meditating.

“Sheldon! You come home this minute!”

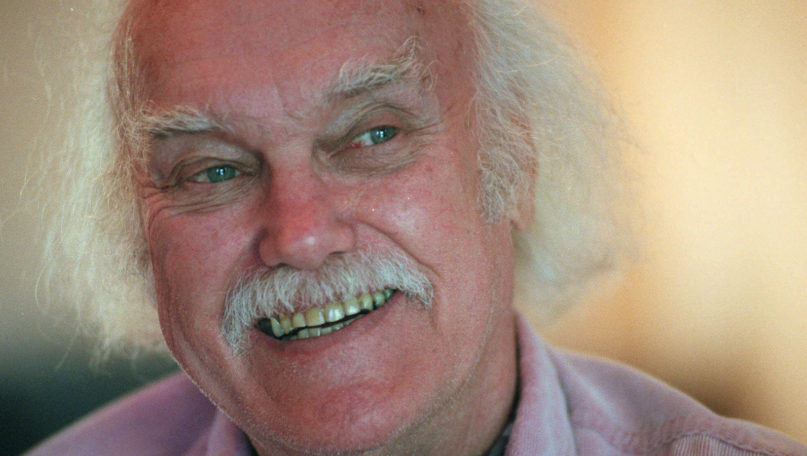

I thought of that joke this morning when I heard that Baba Ram Dass, an author and guru of Eastern enlightenment, New Age religion and LSD who had been a compatriot of Timothy Leary, had died at the age of 88.

Baba Ram Dass. That’s a name that will take many of us back in time — especially my fellow boomers, who had copies of his bestseller, “Be Here Now,” lying around their dorm rooms.

And, yes — while Ram Dass was not the Sheldon Weinstein of the old joke, he did start life as Richard Alpert, the son of a wealthy Boston Jewish family.

Young Alpert made a pilgrimage — from privilege, to a Ph.D. from Stanford, to faculty appointments in psychology and education at Harvard — to hallucinogens, the inner life and enlightenment in a thick soup of Hinduism, transcendental meditation with the maharishi and general New Age musings.

He hung out with Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who shared his dabbling with hallucinogens.

There is much to admire in the life of Ram Dass, as well as a few unsettling aspects as well.

But, this spiritual obituary is not for Ram Dass.

It is for Richard Alpert.

Why did Richard Alpert have to become Ram Dass?

Let’s ask him.

Here he is, talking to Arthur Magida in his wonderful book on rites of passage. He was reminiscing about his bar mitzvah ceremony.

What I mostly remember about my bar mitzvah was that it was an empty ritual. It was flat. Absolutely flat. There was a disappointing hollowness to the moment. There was nothing, nothing, nothing in it for my heart. And I had no idea it could be otherwise. … None of us had the courage, the chutzpah, to question it. You did it, and you got a fountain pen and a dictionary and a party, and that was it.

Go back in time, to the late 1940s and 1950s. Jewish veterans came home. They moved to suburbia. They built synagogues and Jewish community centers.

That should have/could have been a great time for American Judaism. In fact, it wasn’t. It was good for the Jews, but not for Judaism. To have been “religious” in the 1950s was often a function of sociology, belonging and conformity rather than theological conviction or that which might touch the inner life.

American Judaism had become a bland, conformist version of the American civil religion. Writing in the 1990s, Rabbi Wayne Dosick characterized the Judaism of the past generation:

While Judaism got caught up … in the myth that building communal institutions and grand buildings meant the same thing as building Jewish hearts and souls, most Jews began to feel the ache of spiritual emptiness. When Jews came to Judaism seeking God, most often all we found were sign-up sheets for the Hebrew school carpool and pledge cards for the building fund.

Jewish institutions had grown.

But Judaism had shrunken into a pediatric instrument, into life cycle and holiday observances, not touching the core of life.

When you consider how dry suburban Judaism had become, it was easy to see how this could have led to a small revolution. That unfolded in various forms: the havurah movement, and the Jewish flirtation and even integration with New Age religion – which became the Jewish Renewal movement.

There is a Zen parable about a man who is crawling on the floor, looking for a coin that he had lost.

A friend asks him: “What are you looking for?”

“I lost a coin.”

“Where did you lose it?”

“Over there.”

“Then why are you looking over here?”

“Because the light is better over here.”

Jews started to suspect that the “light” was better in different places — and they started to look there. They integrated Buddhism into their lifestyles and philosophy – the JuBu phenomenon. They flirted with Hinduism and Sufism (Islamic mysticism) as well.

Speaking of his experiences praying with Trappists, Native Americans and Sufi mystics, Reb Zalman once said: “I see myself as a Jewish practitioner of generic religion.”

Back to Ram Dass — or, Richard Alpert.

There were many Richard Alperts who wanted a deeper Judaism — a new Judaism — a more inward, nonrational, mystical Judaism.

It turned out that spiritual seekers could find whatever they were looking for in Jewish texts and practices. It was “here all along” (as Sara Hurwitz wrote) in Hasidism — which has led to a vigorous reclamation and recycling of its teachings as neo-Hasidism (see “A New Hasidism,” edited by Arthur Green and Ariel Evan Mayse).

Some years ago, Ram Dass was invited to give a speech on Jewish spirituality.

As a result:

I began to see the heartfelt beauty of being a person who truly loves God in a Jewish way, how it relates to lineage and community, how the mitzvot are all techniques for remembering God, how halacha is a support system.

Which reminds me of Ram Dass’ best line. “Treat everyone you meet like God in drag.”

- See the Divine Image in everyone.

- Realize that we are all pixels in the face of the Shechinah (the feminine presence of God).

- See everyone as if he or she is the Messiah.

- Any person can be a divine messenger.

That works. That totally works.

Welcome home, Richard.