(RNS) — Masculinity in America is an exercise in proving oneself.

In measuring up.

But to what?

In America, there is no standardized assessment to measure when (or whether) one has completed the transition from boy to man. Is manhood reached when one gets their driver’s license? After one has their first full-time job? Achieves an athletic milestone? Gets married? Has a kid? Opens a Roth IRA?

We joke about men losing their “man card.” Is that really possible?

And what if whatever scale one measures themselves against shifts with the currents of culture?

Undergirding most celebrations of hyper-masculine characteristics is a chronic anxiety about whether one is strong enough, successful enough, rich enough, or powerful enough. Because there is not a static definition of manhood, men are left wondering if they’ve achieved the necessary accolades to establish themselves as a man in the eyes of others — particularly other men.

For Christians, of course, there is an ideal man — who invites us to follow his teachings and example. But that doesn’t alleviate the cultural anxiety around masculinity Christian men feel. In fact, following the life of Jesus and his teachings may move Christian men farther from the dominant cultural ideals of our day. Rather than traveling this narrow way, some take on extraordinary mental gymnastics to fit Jesus into our modern molds.

Take, for example, Owen Strachan’s recent tweet gone viral, “Men today are often soft, weak, passive, unprotective. But physical discipline is key for men. Hear Paul: “I batter my body and make it my slave” (1 Cor 9:27). Christic manhood is protective, sharp, watchful. The man who is willfully soft physically is often soft spiritually.”

Men today are often soft, weak, passive, unprotective.

But physical discipline is key for men. Hear Paul: “I batter my body and make it my slave” (1 Cor 9:27).

Christic manhood is protective, sharp, watchful.

The man who is willfully soft physically is often soft spiritually.

— Owen Strachan (@ostrachan) February 18, 2020

Fear is at the heart of these sentiments.

A man who is physically soft and weak is a man unprepared for battle and, thus, easily conquered by others. A man who is passive is easily dominated. A man who is unprotective is a man who will have what is his stolen from him — including his masculinity.

This understanding of masculinity goes back to the founding of America.

As America sought to define itself apart from mother England, American men sought to define themselves in new ways. Whereas men were once defined by the genteel landowner, the new world gave rise to the new ideal: the self-made man. This was a man free from the old world social hierarchies. A new world meant new beginnings; he was now free to determine his own lot in life. Most importantly, he was independent, free from being dominated by another.

But not free from the fear of being dominated by another.

This fear of being dominated by another has necessitated shifts in Americans’ understanding of manhood. In the mid-nineteenth century, a real man was a cowboy fleeing the dehumanization of industry. During WWI and WWII, the ideal man was a soldier fighting Nazis and fascists. Post war, it was the guy with dirty hands carrying a lunch box and a welding torch confident in his ability to shape the world. In the 1990s it was Gordon Gekko in Wall Street insulating himself with financial security.

Pompeo Batoni’s 1767 Sacred Heart of Jesus painting. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

It’s worth noting how everyone of these examples is embodied by predominately white men. It’s no coincidence that black men were denigrated by being called “boy.”

Manhood is a game of winners and losers. And those who are winning make sure the game remains one they can win.

Every time the definition of manhood shifted, it created a crisis within men because the ideal they worked so hard to embody drifted away from them. Where once others saw them as men, this new ideal created the possibility they could lose their place in society to someone else. Rather than lose status and influence, they doubled down on what gave them power.

Strachan’s tweet appears to follow this familiar impulse.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Billy Sunday shared the same fears as Strachan. Men, in his mind, were becoming too feminized. And so he prayed, “Lord, save us from off-handed, flabby-cheeked, brittle-boned, weak-kneed, thin-skinned, pliable, plastic, spineless, effeminate, ossified, three-karate Christianity.” Sunday’s fear about sissified Christian men was happening at a point in American history when women were gaining the right to vote, the androgynous behavior of flappers was all the rage, and technology continued to shift men’s place in the workforce.

In his book “Manhood in America,” Michael Kimmel says, “These crisis points in the meaning of manhood were also crisis points in economic, political, and social life — moments when men’s relationships to their work, to their country, to their families, to their visions, were transformed.”

By a number of indicators, we are at another point in history when our understanding of manhood is in crisis.

It’s likely my generation will be the first generation to earn less than our parents. It’s no wonder men my age are basing less of their identity on earning power, climbing the ladder or even being the primary breadwinner.

Due to egalitarian and economic impulses, the number of women working outside the home has increased. This has forced yet another shift in how men traditionally define themselves.

The #metoo movement accelerated a shift that was already minimizing the role of sexual conquest in proving manhood.

Last but not least, social expectations of men as parents has changed. Rather than busy at work or aloof, men are expected to be engaged and present with their children.

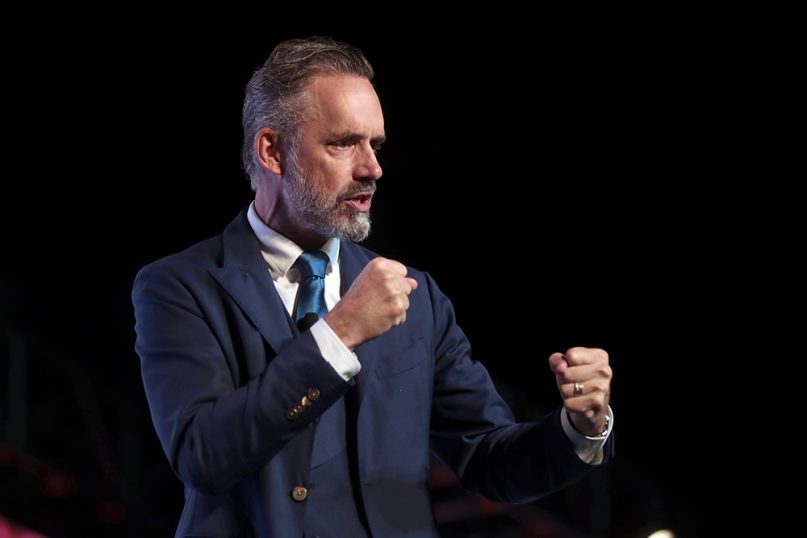

Jordan Peterson addresses the 2018 Student Action Summit in West Palm Beach, Florida, in December 2018. Photo by Gage Skidmore/Creative Commons

We live in a moment when the cultural ideals surrounding manhood are changing. As with any change, there are those who resist it. From secular gurus like Jordan Peterson to deeply religious leaders like Owen Strachan and the Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, those who have benefited from old ideals are pushing back against the change — often using religion to make their case.

The Christian ideal for men is not a construct of the culture. It never has been. Esau would have been more of a man in our culture than Jacob, who liked to hang around the tents and cook. But it was Jacob whom God loved. Paul exhorted men to embody the fruit of the Spirit like gentleness and kindness. Jesus promised that the meek will inherit the earth.

Manhood is rooted in the new man, Jesus. Not American Jesus who has been retro-fitted with certain social ideals. Recasting Jesus in such a way that he affirms our favorite cultural depiction of men neuters the radical nature of his humanity. Jesus was a man who at times was firm, but other times gentle. Was seemingly passive, while actively in control. Was controlled in his anger, and open with his tears. Jesus was strong enough to bear the weight of the cross, and weak enough to be crushed by it.

Jesus is the image of imitation for every man — every human. And he will challenge every ideal.

The gospel of Jesus is not a gospel of proving yourself or measuring up. It’s a gospel of acceptance. Proving yourself is unnecessary. Before you can make your case that you belong, the Father places his signet ring on your finger and calls you “son.” Your title, your place, your identity has been secured by an act of love. Not a show of strength.

Go, and do likewise. You have nothing to prove.

(Nate Pyle is an author, blogger and ordained pastor in the Reformed Church of America. Nate has written two books: Man Enough: How Jesus Redefines Manhood, and More Than You Can Handle: When Life’s Overwhelming Pain Meets God’s Overcoming Grace. Currently, Nate serves as the pastor of Christ’s Community Church in Fishers, Indiana, where he lives with his wife and three children. He tweets at @natepyle79. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)