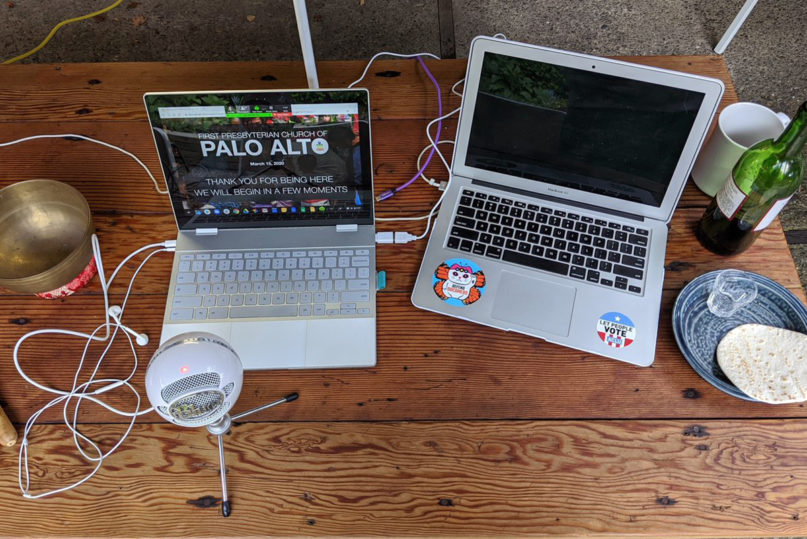

(RNS) — On Sunday (March 15), the Rev. Bruce Reyes-Chow, a Presbyterian minister, began the Christian celebration of Communion as he always has: by reciting prayers over the breaking of bread, recalling a covenant sealed in blood, and invoking the forgiveness of sins.

Except instead of standing at an altar before a congregation seated in pews, he spoke directly into his computer, where members of First Presbyterian Church of Palo Alto, California, stared back at him from a neatly arranged grid of square tiles produced by video chat application Zoom. And instead of taking the consecrated bread directly from their pastor, the attendees of the virtual worship service each held their own supply.

When the minister finished the Communion prayer, the worshippers — some individuals, others families huddled around laptop screens — all lifted their bread to their respective cameras and broke it together.

“We never talked about canceling services, we just talked about doing community differently,” Reyes-Chow said. “We had more people online than we usually have in person this past Sunday.”

With many houses of worship deciding or ordered not to meet in person to avoid spreading COVID-19, whose circulation has reached pandemic levels, many clergy scrambled to shift their services online this weekend using Zoom, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and other digital platforms.

Some religious communities, especially diocesan cathedrals or evangelical megachurches, fell back on technologies they have used for years. On Sunday, President Donald Trump tweeted that he was observing the livestream of a service at Free Chapel, a megachurch based in Gainesville, Georgia, led by Jentezen Franklin, a longtime adviser to the president.

“I am watching a great and beautiful service by Pastor Jentezen Franklin. Thank you!” Trump tweeted.

But even for those accustomed to livestreaming normally well-attended services, adaptations were made for suddenly empty churches. Roughly 25,000 viewers — about 10 times the normal online audience — tuned in to watch the livestream of services at the Washington National Cathedral, where a smattering of clerics officiated worship before a cavernous hall filled with empty chairs. Instead of a shot of the pulpit that captures the sermon most weeks, the cathedral’s digital service cut away to a prerecorded video of Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde speaking directly into a camera from what appeared to be a sofa.

It was not only that there was no congregration to speak to: Budde explained that she could not appear in person next to other clergy because she was in self-quarantine after coming in contact with someone who had tested positive for COVID-19.

Digital or analog, the bishop said, “We are still the church.”

She was followed by the Rev. Michael Curry, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, who also delivered a sermon via video.

“We will fight this particular contagion and all of our preexisting social contagions and divisions by the disciplined labor of love, love working through medical folk, love working through leaders, love working through each one of us who can help and heal — maybe in small ways but add them up and they make a profound difference,” Curry declared.

“Maybe even something as small as voluntarily worshipping God online instead of in person, especially if that would help somebody else,” Curry added.

Betty Matthews and her granddaughter watch a livestreamed worship service of First United Presbyterian Church of Dale City, Virginia, on March 15, 2020. Courtesy photo

While houses of worship have been increasingly using technology to reach more people or simply to bring the folks in the back pews closer, some faith leaders found themselves relying on digital platforms in ways that felt completely new.

“This is a very different Shabbat than we’ve ever had before,” said Rabbi Sharon Brous of Los Angeles-based Jewish community IKAR after opening a Facebook Live session on Friday to “offer some words of Torah.” Brous closed by reciting the kaddish, or prayer of mourning, and encouraged those watching to participate “because I know that there are many mourners among us.”

Members of the community tapped out responses in the comments section as she spoke, such as “Shabbat Shalom.”

Several Buddhist centers are now taking their programs online, and the Buddhist magazine Tricycle has announced a series of free livestreamed meditation sessions “in response to this time of heightened anxiety and isolation.”

The urgent move to digital has required other adjustments. One License, which manages copyrights to many popular religious songs, offered free licenses to use the company’s members’ music during livestream services for at least the next month.

Loosed from having to design in-person liturgy, some churches have abandoned livestreaming in favor of prerecorded services. The Delaware-Maryland Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America called upon professional videographers to film worship services ahead of time that could be streamed by several churches at once.

“We’re delighted you’re able to join us in these challenging times in a way that might be unfamiliar to many of us,” the Rev. Bill Gohl, bishop of the synod, said at the opening of the 30-minute video.

Many houses of worship realized that they had to up their digital game or explore the possibilities of virtual services, sometimes cobbling together a hodgepodge of digital platforms to try out new approaches to liturgy.

At Park Avenue Christian Church in New York City, observers submitted virtual prayer requests during Sunday’s livestreamed service. Preston Hollow Presbyterian Church in Dallas encouraged members watching the livestream to participate in a virtual “passing of the peace” by texting a loved one. And at Urban Village Church in Chicago, leaders are urging members to help craft a digital “liturgy of the hours” by posting prayers and meditations to Facebook and Instagram at set times throughout the week.

Others offered their expertise to newbies: On Monday, City Church in Tallahassee, Florida, posted a form for local churches that lack the resources to film and publish a sermon to sign up and use its video equipment.

Even tech-savvy groups can find a complete shift to digital uncomfortable, however. At Roots, an Islamic “community space” in Irving, Texas, about 200 Muslim young professionals who gather on Monday evenings for coffee and religious lessons strained a bit while trying to replicate the feel of physical togetherness.

“I had to teach it last night to an empty room — it was the weirdest thing,” said Imam AbdelRahman Murphy, the group’s founding ustadh, or teacher. For this week’s children’s activity, Roots is inviting parents to pick up prepackaged arts-and-crafts kits — “prepared with masks and gloves,” he stressed — to use while a leader reads a story during a livestream.

“We see this as a huge blessing,” Murphy said. “(Technology) in this world can be really distracting, but hopefully we’re going to use it for a better purpose.”

When faith leaders ran low on ideas, they turned to digital sources for inspiration. More than 3,000 have joined a private “Clergy and Spiritual Responses to COVID-19” group on Facebook where, in addition to sharing words of encouragement and jokes (“Interfaith Memes for Quarantined Teens”), members spent the weekend peppering one another with questions that ranged from the technological (“What Zoom package to purchase?”) to the liturgical (“Anyone have a prayer for a blessing of the hands of health care workers?”).

One member who self-identified as a “geeky” rabbi offered to serve as tech support for any leader who required it.

For those wary of newer technology, worship organizers worked to make their services accessible. Several included the option to simply call into the service by phone, and Reyes-Chow’s First Presbyterian enlisted “tech deacons” to shepherd less internet-savvy members through the process of logging on.

Denominations pitched in to help clergy pool their resources as well. The ELCA Synod of Metro Washington, D.C., created a database tracking different virtual approaches used by congregations, which ranged from simply posting footage of a service to interactive Bible studies conducted via Zoom.

The Greater Presbytery of Atlanta published a similar database for its member churches and even crafted a COVID-19-specific website replete with helpful links.

Among those links is a training session for pastors on how to officiate a Zoom worship service, led by Reyes-Chow, who is also a former national moderator of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

He hopes to convince his fellow faith leaders that online worship isn’t a facsimile of holy community, but rather simply another way of encountering the divine.

“We’re still worshipping together; it just happens to be taking place in another space,” he said.

Naturally, he hosts the meetings using Zoom, which has forced him to admit that digital connection does have its limits: The service only lets him speak to 100 pastors at a time without paying an additional fee, but he had more than 200 register for Monday’s session.

Adelle Banks contributing reporting for this story.