(RNS) — No one doubted that the Rev. Emil Kapaun, an American Catholic priest from Kansas, had lived a life worth imitating — certainly not the fellow prisoners of war he had almost single-handedly kept alive in North Korea’s Camp No. 5 during the Korean War.

They were so devoted to the military chaplain that they campaigned for nearly 60 years for the Medal of Honor that the priest was finally awarded in 2013.

They were still deeply moved by how Kapaun handled himself as he was led to death at the Death House, a Buddhist monastery on the hill above them where the prisoners in the worst conditions were sent to die.

He had a fever and was delirious — pneumonia was settling in when Comrade Sun, the prison camp’s commandant, burst into the hut with a handful of armed guards and a stretcher. He shot his gun into the air. Then he pointed at the priest.

“He goes,” Comrade Sun said.

“No, he stays with us,” said Lt. William Funchess.

“Leave him,” said Lt. Ralph Nardella.

“Leave him,” cried others, crowding the guards.

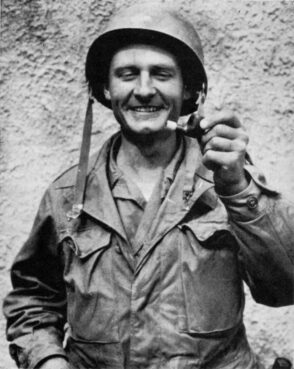

The Rev. Emil Kapaun in his trademark garrison hat that he wore on his rounds in Camp No. 5, a brutal prison in the waterfront town of Pyoktong, North Korea. He died there at the age of 35. Photo courtesy of the Father Kapaun Guild

The doctors, Sidney Esensten and Clarence Anderson, pleaded with Comrade Sun to leave the priest alone. He was recovering. They would get him better. That is exactly what Comrade Sun was afraid of.

“We’ll take care of him,” Comrade Sun said. “He’ll do better with us.”

Soon, men were gathering outside the hut, pushing their way in. They were like ghosts — emaciated and moving in slow motion. They started shoving the guards. The guards shoved back with their rifles. They were scared and about to take aim.

“I’ll go,” came a whisper.

“I’ll go,” Kapaun repeated a little louder. “Don’t get in any trouble over me.”

He handed his gold ciborium over to another officer, William Mayo.

“Tell them I died a happy death,” he said.

He found his voice and told a story from the Old Testament book of Maccabees about how a king threatened to kill a mother and her seven sons unless they all swore off God. She encouraged her boys to “Keep the faith” and watched each of her boys tortured and killed. Then she was killed.

Kapaun nodded to Nardella and handed him the missal: “You know the prayers, Ralph. Keep holding the services. Don’t let them make you stop.”

Phil Peterson touched the priest on the arm: “I’m terribly sorry.”

“You’re sorry for me,” he said. “I am going to be with Jesus Christ. And that is what I have worked for all my life. And you’re sorry for me? You should be happy for me.”

The priest singled out another prisoner.

“When you get back to Jersey, you get that marriage straightened out. Or I’ll come down from heaven and kick you in the ass.”

Lt. Mike Dowe was sobbing.

“Don’t take it hard, Mike,” said Kapaun. “I’m going where I always wanted to go. And when I get there, I’ll say a prayer for all of you.”

Nardella and Bob Wood, who was captured with Kapaun at Unsan, put the priest on the stretcher as their fellow prisoners snapped to attention and formed an honor guard.

The Rev. Emil Kapaun was known for rescuing wounded soldiers on the battlefield. He also made it a point to write to the families of every single soldier who died in combat. Photo courtesy of the Father Kapaun Guild

Anderson looked the priest over once more. The doctor, who knew how much pain Kapaun was in, watched as Kapaun smiled and waved at his men from the stretcher. As the priest passed, tears streaked down the prisoners’ faces.

“To Allah who is my God, I will say a prayer for you,” said Fezi Bey, a Muslim soldier from Turkey.

When Nardella and Wood reached the Death House, they watched as Kapaun made the sign of the cross and blessed the guards. Then the priest looked at the Chinese officers awaiting his arrival.

“Forgive them,” he said, echoing Jesus’ words on the cross. “For they know not what they do.”

He then looked the officer in charge in the eye.

“Forgive me?” Kapaun asked of the officer.

In the years since, Chase Kear, the college pole vaulter, and Avery Gerleman, the youth soccer player, believe that they were miraculously brought back from the brink of death because their families, their communities, even strangers prayed for Kapaun to intercede.

Soon, however, I discovered there was more to becoming a saint than leading a virtuous life and answering intercessory prayers.

Monsignor Robert Sarno is America’s man in the Congregation for the Causes of Saints and had a well-rehearsed explanation for how the saint-making process works.

When I visited his office in Rome, Sarno told me that the Lord, only for reasons he knows, chooses some people in certain moments of history and bestows gifts on them. These gifts are witnessed by the people in his or her community at the time and are interpreted as “signposts” on a road, and they lay out a path to follow in life or for how to get to heaven.

When I visited his office in Rome, Sarno told me that the Lord, only for reasons he knows, chooses some people in certain moments of history and bestows gifts on them. These gifts are witnessed by the people in his or her community at the time and are interpreted as “signposts” on a road, and they lay out a path to follow in life or for how to get to heaven.

In saints, Sarno explained, word of these gifts spreads beyond the community and is handed down for generations. At some point, these gifts become widely known. People start praying for this gifted and holy person to help them.

If the person possesses the stuff of saints, miracles occur — people come out of comas or diseases suddenly disappear without medical explanation.

“I like to say that a saint has two I’s,” he said, warming up. “The ‘I’ for imitation and the ‘I’ for intercession. Once a bishop has determined that the faithful is convinced of this ‘imitatableness,’ if you will, and then has the confirmation that prayers have been answered through the intercession of these individuals, he can start a process, the cause.”

I asked about the importance of lobbying, politics and even “star power.” After all, Pope John Paul II, a man whom Sarno had worked for, was canonized in 2014, just nine years after dying. On the day of the funeral hundreds of thousands overstuffed St. Peter’s Square and chanted “Santo, subito” or “Sainthood, now!”

Soon after, Pope Benedict XVI waived the five-year waiting period after a person’s death to begin canonization. John Paul II had previously curtailed the waiting period from 50 years to five.

Sarno was not biting. And what about the “cold causes,” in saint-making parlance, or the candidacies that go dormant for generations or die altogether?

He got up from behind his desk. My time was up.

“You have to find the miracles they are responsible for,” he said. “The way you do that is with more prayer.”

In truth, it takes more than a miracle to become a saint. Enterprise and organization by a candidate’s supporters are assets. Money and power go a long way, as does luck. How Catholics play in the general culture as well as how they see themselves is vital.

The cause of Kapaun ticked most of those boxes, some stronger than others. His candidacy had to overcome two formidable obstacles, as I eventually found out.

First, he was an American priest at a time when, long after his death, the sexual abuse scandal, specifically prominent in the United States, had brought shame on the church. Being a military man in a time when the world was tired of endless wars and suspicious of Americans didn’t help, either.

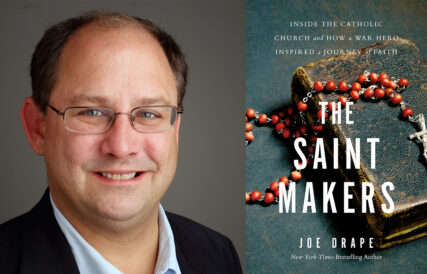

Author Joe Drape and “The Saint Makers.” Photo by Lars Klove for The New York Times

It is hard enough for an American to become a saint — there are only seven of them, after all — and, in the current climate, the cause for Kapaun faced difficult headwinds.

(Joe Drape is a sports writer for The New York Times. This column is adapted from his book “The Saint Makers: Inside the Catholic Church and How a War Hero Inspired a Journey of Faith.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)