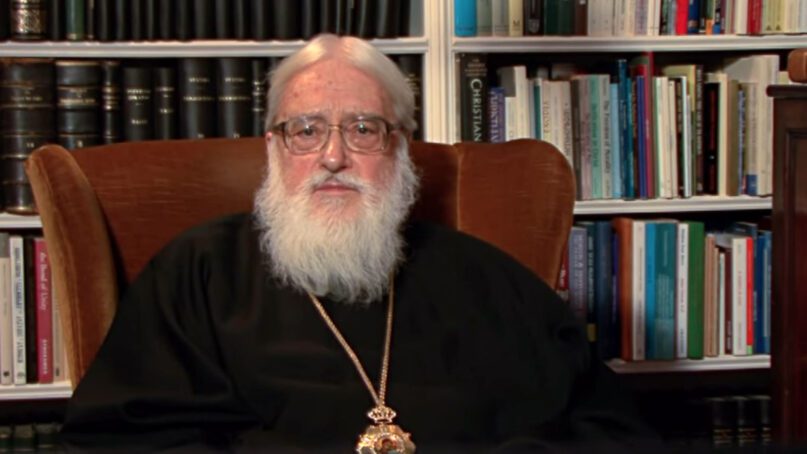

(RNS) — Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, without a doubt the most renowned and popular Orthodox Christian theologian of recent decades, died on Wednesday (Aug. 24) at 87. A convert to Orthodox faith, he became bishop of the see of Diokleia and was considered the most prolific and proficient communicator of patristic theology and Orthodox spirituality in our generation.

For more than 30 years until retiring in 2001, he taught at Oxford University in England (where I studied with him for three years) and was known as an assiduous scholar, punctilious lecturer and conscientious adviser. He also served as parish priest at the Oxford Orthodox community that housed the Greek and Russian congregations. Indeed, what drew many, including me, to Oxford was his rare combination of the scholarly and spiritual, academia and asceticism, of patristic literature and profound liturgy — of Orthodox Christianity as a living and life-changing tradition.

Born Timothy Ware in 1934, he came to Oxford to study classics and theology. He was received into the Orthodox faith in 1958, and after some years spent in monasteries in Canada and at the Monastery of St. John the Theologian on the island of Patmos, where the Book of Revelation was written, he was ordained a priest in 1966. He was elected to the rank of bishop in 1982, and later metropolitan, a title of higher distinction in the Eastern Orthodox Church. For the rest of his life he was an avid researcher, prolific writer, brilliant exponent and desired speaker.

He was a punctilious and measured man. The day we first met, in September 1980, we had lunch at his academic home, Oxford’s Pembroke College. Ware brought along a stack of books for me, proposed an essay title and said he’d see me again in three weeks. Otherwise we talked about the menu of the dining hall. The next time we met at his parental home. Ware served me tea and a banana on a plate, with cutlery. He neatly peeled and sliced his banana; I obliged him by drinking the tea, but told him I preferred to take the fruit back to my room. For a young student accustomed to more casual ways in my native Australia and in Greece, it was a brusque awakening.

The world will remember Ware as the author of “The Orthodox Church,” still the quintessential introduction to the Orthodox Church, and its companion, “The Orthodox Way.” But for me he will always be first and foremost the translator, with Mother Mary of the Orthodox Monastery of the Holy Veil in France, of “The Festal Menaion” and “The Lenten Triodion,” the core liturgical books of the Orthodox Church, completed in 1969 and 1977 respectively.

With Gerald Palmer and Philip Sherrard, he edited the complete text of “The Philokalia,” a collection of writings by early church and Orthodox mystics. In 1995, Denise Sherrard wrote to tell me that her husband completed the draft of the translation only weeks prior to his repose. Ware, for his part, finished with the final proofs of the fifth and final volume just weeks before he died, attending to its index until his last breath.

Ware’s unique and provocative combination of scholarship and spirituality was a powerful influence. Comfortable serving as a priest at Holy Trinity Church as he was researching in the Bodleian Library and chairing the faculty of theology, he spent countless hours visiting patients in hospitals and parishioners in restaurants or businesses. He was as much on fire delivering a lecture on the desert fathers or the Palamite controversy as he was delivering a sermon on a solemn Holy Week service or a regular Sunday liturgy — all with a distinctive and ingenious wit.

In his first sermon as bishop, in June of 1982, he suggested that the diverse lives of the saints reveal that each of us is a unique way of, and to, salvation. In his weekly sermons, he emphasized the power of the name of Jesus, the call to self-awareness, the expectation of trials and the primacy of thanksgiving. He underlined prayer as offering glory, instead of listing complaints, and interpreted liturgy as the occasion for the Lord to act rather than an opportunity for us to worship.

He kept track of these sermons: He once admitted that he was repeating a sermon from five years earlier, shrewdly observing that it was all right to repeat a sermon, so long as it wasn’t a bad one the first time around.

But it is as a father confessor and spiritual guide that he may have made his most lasting mark. Arguably the most vivid image I have of Ware is the endless line of parishioners approaching the upper left corner of the nave at Holy Trinity at Great Vespers on Saturday Vigil. They came from many backgrounds, education levels and cultures, all there to offer a word of confession and receive a word of consolation.

Ware would exhort you to pay attention to little things: the icon you venerated, the person you encountered, the gift of the present. He was convinced of Christianity’s constant surprise and limitless wonder; it could never be contained or constricted to a stagnant past and stereotypical tradition. It found you where you are: To Ware, it made perfect sense that reorganizing one’s index cards and filing system could be used as a prudent and beneficial Lenten discipline for the soul.

Ware will be remembered far beyond Oxford, or even Orthodoxy. He was as confident debating with Anglican and Catholic clerics or theologians as he was among Greek, Russian, Serbian or Romanian Orthodox thinkers. He was longtime editor (with George Every and John Saward) of the pioneering journal Eastern Churches Review and lifelong advocate (with the likes of the Rev. Lev Gillet) for the Anglican-Orthodox Ecumenical Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius. He served as joint president of the international commissions for Orthodox-Anglican and Orthodox-Roman Catholic dialogue, and despite concerns and reservations he promoted and participated in the Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church in 2016.

Thoroughly ecumenical, he was an English gentleman through and through. Orthodox to the bone, he nevertheless considered himself a perennial apprentice of the faith, once stating how he looked forward to browsing through heaven’s library.

He never imagined himself contorting the Orthodox faith to personal conventions or apprehensions, but ever perceived himself as willing to be shaped, perhaps surprised by its newness. It is not coincidental that his personal memoir, “Journey to the Orthodox Church,” appeared only a decade ago, when, as a mature critical thinker, he could discern how the church had changed over his lifetime. He emphasized the struggle to espouse the heart of the Orthodox faith as well as to embrace its paradoxes, antitheses and polarities.

In this way, he was capable of both informing and criticizing developments in the Orthodox Church, Greek and Russian alike. He was also humble enough to recognize his limitations and miscalculations. He admitted that the 2007 Document of Ravenna “on communion, conciliarity and authority,“ which concerned some theologians because it highlighted the authenticity of a universal primacy, was in fact sound. He encouraged discussion of women’s ordination along with dispassionate conversation on gender and sexuality — both of course to the rancorous disapproval of the usual suspects. He endorsed an Orthodox ecological doctrine as fundamentally and essentially rooted in the dogma of creation and incarnation.

I never stopped being his student. He was supportive at every new dimension and turn of my ministry and teaching. He guided and read everything that I wrote over the last 30 years, which included preparing — when he was already quite ill — the foreword to my latest publication on the fifth-century elders from Gaza, Barsanuphius and John, whose letters he introduced me to as his student.

I was delighted to dedicate this book to him; and I was elated that he held it in his hands only days before surrendering his spirit to the Lord. I can imagine him right now waiting for the grandfather clock to strike with precision for the moment when he will open the door to his book-strewn heavenly library.

(John Chryssavgis, the author of more than 40 books on Orthodox theology and spirituality, is archdeacon of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and special theological adviser to the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)