WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass. (RNS) — Having lost the First World War, Germany had also “lost the peace” — the treaty signed in Versailles in 1919 awarded the Allies billions in reparations and forced Germany to cede territory that had fed its rise to power and prosperity. The fledgling Weimar Republic was faced with rebuilding even as the once mighty Reich was mired in debt and economic depression.

Out of this bleak reality Paul Goesch, a German expressionist, architect and spiritualist, joined with a group of like-minded colleagues to imagine a new future. Goesch’s designs are simultaneously monumental and childlike — and deeply religious, with traditional triumphal arches and Gothic facades rendered in organic lines and decorated with angels and visionary images.

Now, Goesch’s work is being shown in its own dedicated exhibition for the first time outside of Europe.

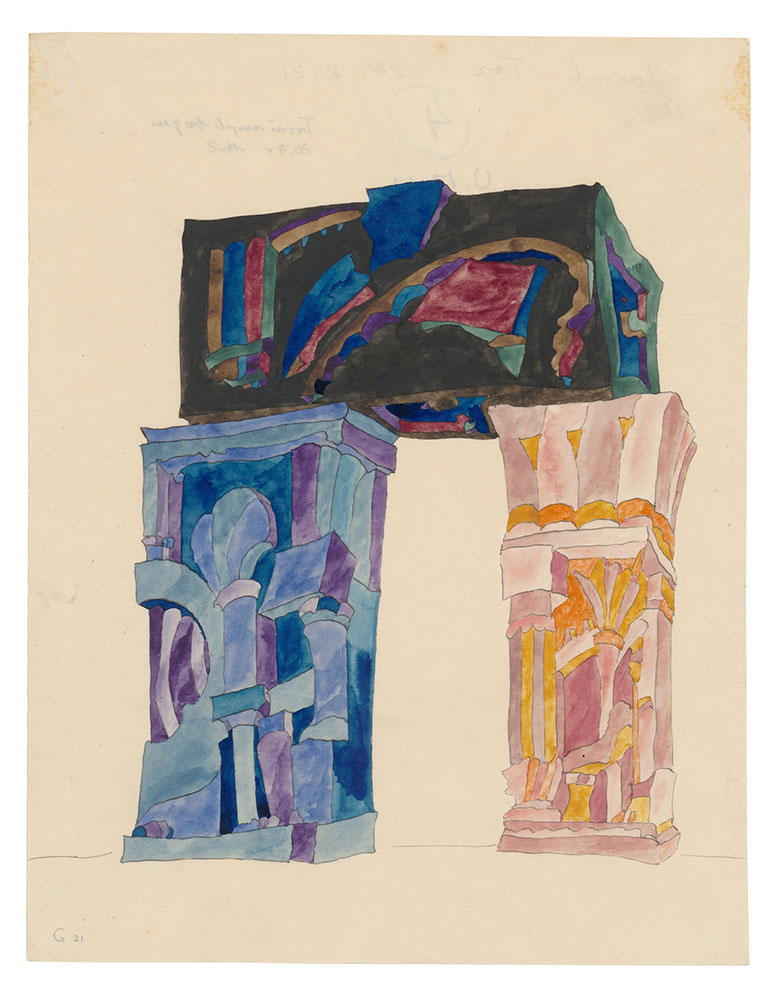

Paul Goesch, “Architectural composition (Triumphal arch) or Visionary design for a gateway,” c. 1920–21, graphite and gouache on watercolor paper. Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, DR1988:0241

The exhibit, titled “Portals” after Goesch’s fascination with doorways and facades, is at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, through June 11. On display are a little more than 30 of the almost 250 Goesch pieces made in just two years, between 1920 and 1921, all of them owned by the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

The intimacy of Goesch’s work grew out of the immense and collective spiritual trauma suffered by the Germans, whose collective psyche had been crushed by war. Robert Wiesenberger, curator of contemporary projects at the Clark, described it as “a moment of rebuilding in every sense.” Goesch was just one of a community of architects reevaluating how architecture represented ideas about war, spirituality and social values.

This community Goesch belonged to was known as the Glass Chain, named after the favored material of their works, which were in large part fantasies, not plans for real constructions. “This group of architects who were imagining what the future of architecture should look like, especially at a moment when no one could build because of material shortages and hyperinflation and lack of commissions, so everything was so-called paper architecture,” Wiesenberger said.

Paul Goesch, c.1920. Collection: Freundeskreis Paul Goesch e.V., Cologne.

While inspired by the experimentation of contemporary architects — they pored over the new work of international innovators such as Antoni Gaudí and Frank Lloyd Wright — the Glass Chain architects were freed by their inability to realize their designs and strove to create new and inventive forms for buildings.

“They were all dreaming, dreaming big and thinking about what it would mean to rebuild and imagine a new society, a new human,” said Wiesenberger.

At the same time, Goesch’s facades used the visual language of Germany’s ancient Gothic cathedrals to connect with his culture’s spiritual past and revive it. “There’s definitely a fascination with the medieval and the Gothic and the forms of the cathedral as much in terms of form as in terms of metaphor and the idea of a spiritual reawakening — and the power of architecture to represent this kind of utopian possibility,” Wiesenberger said.

The cathedrals and churches that shaped the skylines of medieval cities were imposing structures, which marked the center of city life, both spiritual and secular. While the spires signaled a Christian faith, “the idea that architecture has this kind of organizing, central, highly visible, communal function sort of transcends religion,” said Wiesenberger.

Born into a Lutheran family in 1885, Goesch converted to Catholicism while still in his youth but was drawn to a spiritualist movement of the 20th century known as anthroposophy, a blending of Eastern religion, pre-Christian European mythology and humanist philosophy.

From this amalgam of beliefs come the unique visions of Goesch’s work. An angel sits in a small throne atop a column adorned with fish and flowers, symbols of natural bounty. A temple styled like a Dagoba is surrounded by structures resembling crucifixes. A domed chapel uses the likeness of faces and heads to adorn its walls in lieu of sacred imagery.

Goesh’s visionary designs, combined with his playful and irreverent use of color and ornamentation, give a glimpse of religion and spirituality that is not repressive, but instead celebrates humanity.

“Even if the pointed arch appears in many of his drawings — and that’s a Gothic form — there’s a great intimacy in the drawings,” said Wiesenberger. “Even though scale is not really clear whether they’re miniature or massive, they generally seem to be on the more intimate side.”

Paul Goesch, “Architectural composition (Triumphal arch) or Visionary design for a freestanding gateway,” 1921, watercolor and gouache over pen and black ink on tracing paper. Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, DR1988:0242

The exhibition explores Goesch not only as a spiritually attuned visionary, but also as a neurodivergent one. “I think part of the word ‘visionary’ refers both to things that are unbuilt or unbuildable, and also the idea of having visions, which, as a schizophrenic person, (Goesch) did,” said Wiesenberger. Goesch’s portals and entryways, symbolic of the passage between this world and the next, may also be read as doorways to the altered perceptions of a schizophrenic.

After 1921, Goesch would spend much of the rest of his life institutionalized, and he died as a ward of the state shortly before his 55th birthday. According to the Clark’s history accompanying the exhibition, “After years of institutionalization, in 1940, Nazi doctors murdered Goesch in the former Brandenburg prison as part of the ‘Aktion T4’ involuntary euthanization program.”

Though his life and artistic vision were cut short by persecution, Goesch’s ideas and expression thereof live on to inspire others to this day to rise above material limitations and imagine what utopia could be.

Paul Goesch, “Visionary design for an arch,” c. 1920–21, graphite and gouache. Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, DR1988:0254