LONDON (RNS) — Two weeks before Christmas is normally one of the busiest times of the year for the Archbishop of Canterbury, spent preparing his sermon for Canterbury Cathedral’s Christmas morning service that makes the news on British television on Dec. 25.

But this is not a normal Christmas season for outgoing Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby, who has entered an unaccustomed period of silence after first stepping down because of the Church of England’s handling of one of its worst abuse scandals, followed by his disastrous valedictory address in the House of Lords last week.

It seems we will hear no more from Welby before he officially leaves his post on Jan. 6 — besides giving up his Christmas sermon, he will not deliver his usual televised New Year’s Day message, the BBC has confirmed. Instead, officials at Lambeth Palace said, this year he will spend the holidays privately with his family.

Welby’s reputation was badly tarnished by the Makin Review, an independent investigation of the church’s response to allegations of abuse against John Smyth, a prominent layman who ran summer camps in England and Zimbabwe. After the report appeared in early November, confirming that Welby had been slow to isolate a suspected abuser, Welby announced he would resign his post a year before he turned 70, when Archbishops of Canterbury traditionally quit.

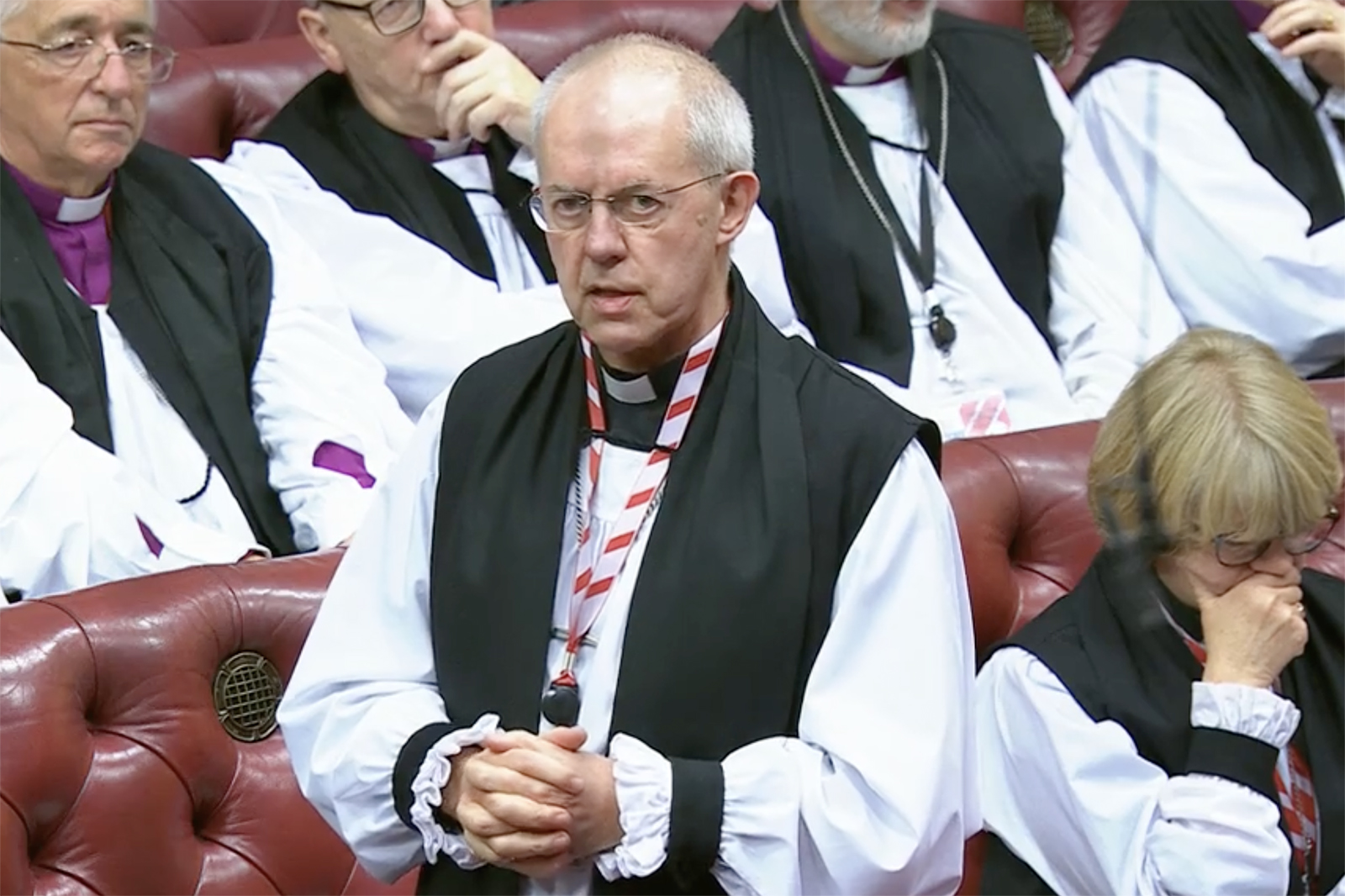

An ex officio member of the British Parliament’s House of Lords, Welby rose to make his farewell remarks Thursday (Dec. 5) during a debate on housing and homelessness — issues on which he has commented many times during his episcopacy.

His speech did eventually address those topics, but not initially. Instead, Welby began by seeming to make light of his resignation and the serious safeguarding failures detailed in the Makin Review. After joking about a 14th-century predecessor who was beheaded, Welby suggested, “If you pity anyone, pity my poor diary secretary, who has seen weeks and months of work disappear in a puff of a resignation announcement.” He went on to thank fellow members of the Lords for their supportive messages over the past few weeks.

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby, center, addresses the British Parliament’s House of Lords, Dec. 5, 2024. (Video screen grab)

While some peers and the fellow Church of England bishops seated behind Welby on the parliamentary benches appeared to be amused, the bishop of London, Dame Sarah Mullally, appeared to be mortified, holding her hand across her face. The squirm of embarrassment was also felt by viewers at home and by commentators.

One of Smyth’s victims told The Guardian that he was appalled by Welby’s speech, saying, “I have never come across anyone so tone-deaf.”

The bishops who oversee anti-abuse efforts — Joanne Grenfell, Julie Conalty and Robert Springett — released a letter sent to survivors and their advocates the day after the speech, responding to a rash of emails expressing anger about Welby’s speech.

“Both in content and delivery, the speech was utterly insensitive, lacked any focus on victims and survivors of abuse, especially those affected by John Smyth, and made light of the events surrounding the Archbishop’s resignation,” they wrote. “It was mistaken and wrong. We acknowledge and deeply regret that this has caused further harm to you in an already distressing situation.”

Welby issued a mea culpa the same day, expressing regret at sins of commission and omission. “I understand that my words – the things that I said, and those I omitted to say – have caused further distress for those who were traumatised, and continue to be harmed, by John Smyth’s heinous abuse and by the far-reaching effects of other perpetrators of abuse,” he said in a statement.

“It did not intend to overlook the experience of survivors or to make light of the situation – and I am very sorry for having done so. It remains the case that I take both personal and institutional responsibility for the long and retraumatizing period after 2013, and the harm that this has caused survivors.

“I continue to feel a profound sense of shame at the Church of England’s historic safeguarding failures.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury has sat in the House of Lords dating back to the 14th century. Since 1847, 25 fellow bishops have been granted seats in Parliament’s upper chamber, known as the Lords Spiritual: the archbishops of Canterbury and York, and the bishops of Durham, London and Winchester, plus the 21 longest-serving bishops in other dioceses.

The Lords Spiritual can vote, speak in debates and scrutinize legislation, but their position in Parliament is chiefly a reminder that the Church of England remains fully entwined with the establishment: Welby, as Archbishop of Canterbury, crowned King Charles III at his 2023 coronation.

Welby’s final speech may well boost the cause of those who wish to see bishops removed from the House of Lords, and while it has become a convention for the outgoing Archbishop of Canterbury to be given a peerage, enabling them to continue to sit in the Lords after retirement, it seems unlikely that Welby will be given the honor.

Meanwhile, the Church of England and the wider Anglican Communion are focused on the search for Welby’s successor. A protracted process, likely to take at least six months, begins with the Crown Nominations Commission, which makes a recommendation to the prime minister, who then passes it to the king, who makes the actual appointment as both head of state and Supreme Governor of the established Church of England.

The Anglican bishops attending the Lambeth Conference prepare for their group photograph during the 2022 Lambeth Conference at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England, July 29, 2022. (Photo by Neil Turner for the Lambeth Conference)

The CNC consists of the archbishop of York, another senior bishop, six members of the church’s ruling body, the General Synod, three representatives of the diocese of Canterbury and five members chosen from the global Anglican Communion.

Concerns have arisen in the past year about the functioning of the CNC, which also assesses candidates for all Church of England bishoprics. Two-thirds of CNC members must support any nominee, giving outsized power to a minority opposing a candidate’s views on, for instance, blessings on same-sex relationships.

Earlier this year the CNC failed to reach consensus on candidates for the next bishop of Ely, putting the decision off until spring. Last December, a similar problem arose with the appointment of the new bishop of Carlisle, and the see remains vacant.

Lack of consensus could be a particular risk in the nomination of a candidate for Archbishop of Canterbury, especially since Welby gave representatives of the wider, generally more conservative Anglican Communion a bigger presence on the CNC.

Among likely candidates are Martyn Snow, 56, bishop of Leicester, lead bishop for the highly contested issue of sexuality; Graham Usher, 54, bishop of Norwich, keen on environmental issues; and the conservative evangelical candidate, Paul Williams, 56, bishop of Southwell and Nottingham.

Two women are also thought to be in the running: the highly respected Guli Francis-Dehqani, 58, bishop of Chelmsford, an Iranian refugee whose core issue is housing and who has none of Welby’s corporate style, and Rachel Treweek, 61, bishop of Gloucester and the first woman bishop to sit in the Lords.

Stephen Cottrell, the popular archbishop of York who will keep the Anglican ship afloat from now until the appointment of Welby’s successor, is not considered a likely candidate because he is already 66 and would be too close to retirement age at the time of appointment.

Also now being mentioned for Canterbury is the bishop of Newcastle, Helen-Ann Hartley, the only bishop to call publicly for Welby’s resignation last month. A petition is now doing the rounds in England, calling for her to be appointed.