(Matthew Streib is traveling across the country on his bicycle exploring religious sites that are inspiring and uniquely American. You can read more about his travels at www.americanpilgrimage.com.)

JOHNSTOWN, Pa. _ Inside a small log cabin, 20 people are singing at the top of their lungs – but it sounds like a hundred. At the Friends General Conference Gathering, they are reviving in an almost-forgotten form of American spiritual folk song, shape note singing, that many would rather forget.

With four-part harmony and a cacophony of notes, it’s reminiscent of many stereo systems playing at the same time, some miscued and some warped. A common phrase about the art is “Some people will walk 10 miles to sing shape note, but other will walk 100 miles not to hear it.”

But at least that shows that some people love it, and often this is due to the art’s honest, stark, and explicitly Christian themes.

“It’s not pretty music,” says Linda Selph of Berkeley, Calif.., who has sung shape note for four years. “But it’s beautiful music. It’s not pretty, and it’s not polite, and that’s what I like about it. It is full soul music.”

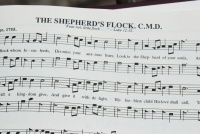

Shape note singing gets its name from its unique songbooks, which replace standard musical noted with symbols for easier comprehension by the laity. Once America’s prevailing religious music, it fell out of fashion after the Civil War. In the mid-1900s, many thought it was gone, until researchers were surprised to find it hanging on in the rural Deep South.

Now, it’s in revival, especially in Baptist and Church of Christ congregation in the South. But Quakers in the rest of the country are also doing their part, and shape note events have been an increasingly popular pastime at the last five yearly gatherings.

“This is music that is rooted in the earth and the people, not in somebody’s intellectual idea of what music ought to be like,” says Paul Landskroener of Minneapolis. “Many of us come into it for the music, but it ends up in our soul and it has changed our lives spiritually.”

But why would Quakers, who value silence so much, espouse a musical style which is boisterous and untamed?

For Landskroener, it’s the raw emotion. He says that the early settlers experienced life in a way that modern American can’t reach, especially in their intimidate knowledge of the circle of life. “That’s a gift that those of us in the privileged classes are deprived of is that level of life and vitality over the whole range of life. They give us hope, strength, courage, and they help us to love each other better.”