At the end of his Social Contract, Rousseau argues for a civil religion that requires all citizens to be uber-tolerant of religions not their own: “Anyone who ventures to say: ‘Outside the Church is no salvation’ should be driven from the state,” he wrote.

That’s the position the Russian Supreme Court took Thursday in banning the Jehovah’s Witnesses and seizing their property under the Russian Federation’s 2006 anti-extremism law. The law prohibits the dissemination of “propaganda” that promotes religious “supremacy.”

Along with being pacifists, opposing blood transfusions, and generally abstaining from civic life, the Witnesses do indeed promote the idea that theirs is the only true religion. As their Russian spokesman told NPR, “This is the nature of any religion, otherwise, why are you following a false religion?”

But in Putin’s Russia, religious liberty must bow before the Rousseauian imperative of state solidarity.

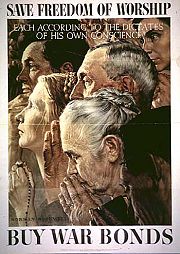

Most Americans don’t see things that way. We may disapprove of those who go around proclaiming that Heaven is exclusively reserved for members of their church. We don’t consider them enemies of the state.

But that doesn’t mean we’ve got religious freedom all sorted out in the U.S. of A. To the contrary, we find ourselves in a particularly unsettled time, free-exercise-wise.

For the past several years, we’ve been consumed with debates over the extent to which religious claims should be allowed to supersede anti-discrimination laws and healthcare mandates. On both sides, partisans have dug in, seeing threats to civilization in even the smallest calls for compromise.

Last year, in the Supreme Court, it was Zubik v. Burwell — the so-called “Little Sisters” case, whereby some religious non-profits insisted that it would violate their religious freedom simply to file for an exemption from the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that they provide free contraceptive coverage to their female employees. Because that would “trigger” the provision of such coverage by another party.

This year, it’s Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, which concerns the exclusion of a religious preschool from a Missouri program giving grants to non-profits to resurface their playground with recycled tires. Missouri’s Constitution prohibits provision of public funds “in aid of any church, sect or denomination of religion.”

The question before the Supreme Court is whether the prohibition, at least in the case of that exclusion, violates the U.S. Constitution.

In an amicus brief, the American Jewish Committee, which supported the government’s position in Zubik, took Trinity Lutheran’s side, arguing reasonably that where a “program or activity at issue is inherently secular in nature and would be perceived by the public as such” religious organizations should be entitled to apply for public funds “on the same terms as secular organizations.”

As it happens, Missouri’s newly elected Republican governor recently rescinded the exclusion, thereby conceivably rendering the question moot. But just before oral argument Wednesday, both sides urged the justices to go ahead and decide the case on the merits — something the justices seemed inclined to do, and in favor of Trinity Lutheran at that.

What has made this case so neuralgic for strict separationists and so exciting for accommodationists is that, as Emma Green makes clear over at the Atlantic, the facts of the case are so religiously innocuous. “On its surface,” writes Green, “Trinity Lutheran seems like it’s just about keeping kids’ knees from getting scraped.”

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the jurisprudence of the religion clauses was sufficiently settled that the Court could be depended on to render a decision that would do no more than move the boundary between the constitutional guarantees of free exercise and establishment a little one way or another.

Nowadays — and with a new accommodationist justice on the Court — all bets are off. In the name of religious freedom, religious organizations could well be made eligible for all sorts of public funding.

To be sure, nothing comparable to Russia’s liquidation of the Jehovah’s Witnesses is in the offing. But the stakes are big enough.