I well remember the 1980s, when I was growing up. My generation saw scandal after scandal with “name it and claim it” preachers whose own lavish lifestyles held out the promise that God could and would make followers rich. Preachers like Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker were proponents of prosperity theology, an offshoot of Pentecostalism that envisions faith as a spiritual power to unleash wealth and health.

I well remember the 1980s, when I was growing up. My generation saw scandal after scandal with “name it and claim it” preachers whose own lavish lifestyles held out the promise that God could and would make followers rich. Preachers like Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker were proponents of prosperity theology, an offshoot of Pentecostalism that envisions faith as a spiritual power to unleash wealth and health.

Some scandals are still going on—late last month, for instance, David Yonggi Cho, the pastor of the world’s largest prosperity church, was convicted of tax evasion and fraud, and Joyce Meyer and others are still under investigation in the U.S. But overall, we’ve transitioned from the “hard prosperity gospel” of the 1980s to what Duke historian Kate Bowler identifies as a therapeutic softer sell offered by Joyce Meyer, Joel Osteen, and others.

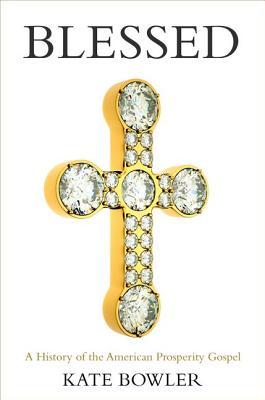

I talked with Bowler, the author of the outstanding Oxford book Blessed, to find out more about the growth of the prosperity gospel’s softer side. — JKR

RNS: How did we move from the excesses of Jim and Tammy Faye to something like Joel Osteen’s gentler approach?

Bowler: I think the prosperity preachers took their cues from culture. People were fed up with the hard sell and the kind of “greed is good, more is always more” culture. We became much more accustomed to a kind of darker postmodernism that said that people could not always be trusted.

The main difference was having accepted therapeutic idioms as being the primary language of prosperity. They have now moved into the realm of feelings as the primary spiritual battleground that Christians need to use to wage war against demonic forces. It allows for a gentler “I’m here to help you” approach, saying, “I’m not here to sell you products, but to offer you tools.”

In the 1980s there was this carnival atmosphere, emphasizing all the stuff, all the material wealth that God could get you. It was the triumph of the power suit, and anything that glittered. We saw heavy gold watches and jewelry, [and] power suits put through a pastel machine.

That would not play so well now. In the 1990s, you started seeing casual dress, with less of a difference between the leaders and the followers. They started looking more like sports motivational figures.

RNS: Is the movement changing in other ways?

Bowler: I think the most exciting frontier for the prosperity gospel is white evangelicalism. The trickiest thing for the “soft” preachers is that their message looks a lot like ordinary optimism. White evangelicals love an optimistic, practical, culturally sensitive approach, and the prosperity gospel offers really good tools to help them make that kind of expansion.

For example, there’s a new evangelical prosperity gospel church in North Carolina [Elevation Church in Charlotte] that gave away iPods at their opening. Their pastor, Steve Furtick, has a very robust prosperity gospel and is taking the evangelical world by storm. Steve Furtick looks exactly like a culture-savvy evangelical, but actually has the theological apparatus of the prosperity gospel behind him.

I find it fascinating that some white evangelicals are taking a page from the playbook of Pentecostals, offering parishioners more. They want to get more out of this life before life is over.

RNS: In your book you tell some stories about people you interviewed who had not gotten the healings they prayed for. Sometimes, when people continue in illness or addiction or debt, they just disappear in shame.

Bowler: A hard prosperity gospel will emphasize the once-and-for-all character of these kinds of blessings. There is a sense in which your life really should demonstrate the power of your faith.

There are a few options open to someone who has prayed but not been healed. Sometimes they’re told there is a season, and their season is not yet. It’s a ritualized waiting; waiting is a huge part of what they do. They can also take more aggressive measures, like in the annual cycle of revivals. At revivals, people can ask for the big things, and will also take on bigger sacrifices, like making a larger donation or doing a fast. It’s a more herculean effort. Lastly, they can take a break or just leave. That’s something you see when people feel they’re not able to live up to the standards of their churches.

RNS: Thank you!