CARY, N.C. (RNS) — At a Bible study on a weekday evening, Lutheran minister Daniel Pugh paced before a group of 50 church members in cargo shorts and a plaid button-down shirt talking about Adam and Eve.

Clutching a hand-held remote he clicked through a PowerPoint presentation, telling members of Christ the King Lutheran Church that one way to interpret the story of Adam and Eve is as a coming-of-age allegory about a pair of carefree teens caught red-handed having sex.

Christ the King Lutheran Church in Cary, N.C. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron.

In this, alternative reading of The Fall, the “forbidden fruit” offered to Eve in Chapter 3 may be a metaphor for sex, he said, and the “serpent” may be a metaphor for a penis.

Lutherans have certainly come a long way since their namesake, Martin Luther, nailed his 95 theses to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg, Germany, 500 years ago this month, sparking the Protestant Reformation.

These days, the largest U.S. denomination to trace its heritage to the great reformer, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, is struggling to reverse a decline in membership among its 9,252 churches.

The traditional sanctuary at Christ the King Lutheran Church in Cary, N.C. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Its successful churches, such as Christ the King, located in a bedroom community of Raleigh, are pushing forward with a new vision, one that has less to do with upholding the purity of Luther’s theology and more with the spirit of Luther’s reform agenda.

That spirit of reform is evident in the casual clothes sans-collar Pugh wears for Bible study, in his embrace of technology and audio-visual enhancements — the Bible study is posted to the church’s YouTube channel — and in his theological exploration that brings recent academic scholarship into the pews and challenges members’ understanding of their faith.

[ad number=“1”]

“This is a look at the Adam and Eve story in a way I’m sure you’ve never heard a pastor talk about before,” Pugh, 34, told his listeners at the outset, cautioning them: “This Bible study is going to be more adult than you’re used to. This Bible study will talk about sex and morality.”

Christ the King Lutheran Church wants to move beyond the hidebound traditions of American Protestantism, take risks, attract younger people and make Christianity more relevant to the 21st century.

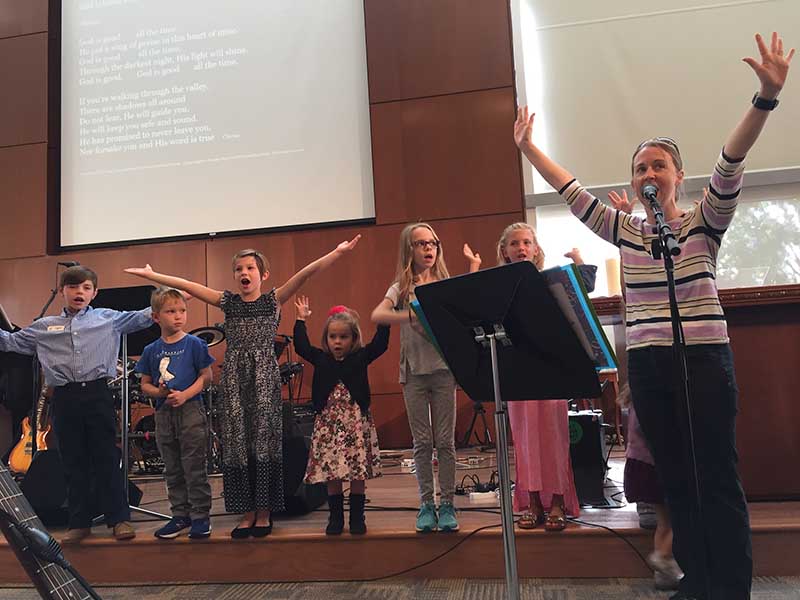

Julie Schmidt, right, leads a children’s sing-along before Sunday school at Christ the King Lutheran Church in Cary, N.C. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

“A lot of times churches are trying to preserve the legacy of who founded the congregations founded long ago,” said Elizabeth Eaton, the presiding bishop of the ELCA. “When you try to hold on to something so tightly, you strangle it. Taking a risk while being faithful to the core message of grace is my advice.”

Luther famously broke with the Roman Catholic Church over his conviction that faith alone leads to salvation in heaven and that the Bible is the sole source of legitimate authority for Christian believers. But those theological controversies have receded in significance.

More important to many Lutherans today, is Luther’s emphasis on freedom that comes from divine grace, on offering worship in the language and culture of the day and making it relevant to a new generation.

The share of Americans who identify with mainline Protestantism has been shrinking significantly. A recent Pew Center study found that just shy of 15 percent of Americans affiliate with the mainline. (Among millennials born since 1981, only 11 percent identify as mainline Protestants).

The ELCA saw its membership decline to 3.5 million members in 2016, down from 5.2 million in 1988 when the denomination was formed as a merger of three other smaller Lutheran groups. Today, 40 percent of its churches have between 50 and 100 worshippers each Sunday.

Christ the King, with 1,420 members, is determined to change that trajectory.

[ad number=“2”]

Evangelism in a parking lot

Like many older mainline churches across the country, Christ the King went through a period of stagnation.

Morale flagged. Conflict escalated. Clergy burned out. Members left.

The church was started in 1964 when Cary was still a sleepy suburb with fewer than 5,000 residents. But the church benefitted from the town’s explosive growth — now about 162,000 residents — as more people flocked to the South in search of better jobs and safe, family-friendly neighborhoods.

At its peak, Christ the King had 2,000 members. But when the church hired the Rev. Wolfgang Herz-Lane — who, like Luther, was born in what is now Germany — as senior pastor a year ago, only about 400 were attending Sunday services.

“It became really clear that what was happening here is what happens in so many of our churches: People were faithfully managing their decline,” said Herz-Lane.

Senior Pastor Wolfgang Herz-Lane gives a Martin Luther toy to a child during a church service. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

As the membership and offerings declined, church leaders cut staff and programs — accommodating the decline and managing it rather than trying to reverse it.

Herz-Lane, who served previously as bishop of the Delaware-Maryland Synod of the ELCA, had ideas about what could be done.

Herz-Lane first came to the U.S. to work in a poor, inner-city church in Camden, N.J., as part of an overseas service program. He quickly learned about dislocation, malaise and social injustice.

RNS graphic by Chris Mathews

Though Christ the King’s problems were of a different order — its members are mostly affluent and white — he saw a challenge. When he was defeated for his second term as bishop, he took the job of senior pastor in Cary hoping to turn the church around.

At its core, his plan consisted of extending an invitation and building relationships.

“Lutheran churches are terrible about evangelism,” he said. “They think religion is a private matter. But Jesus is clear: Go and make disciples.”

MaryJane Selgrade, a longtime member who chairs the church’s outreach board, points to the church’s next-door neighbor, Cary High School, as an example of Herz-Lane’s new emphasis on building relationships.

For years, parents have been driving through the church’s parking lot each morning to drop off and pick up students. This was one of the first things Herz-Lane noticed.

“He said, ‘God is bringing 150 people to our parking lot every morning and what are we doing about it?’” Selgrade said.

As the school year started, church members began offering pencils and doughnuts to drivers and passengers. On Ash Wednesday, they offered “ashes to go” as they pulled through the parking lot, smudging foreheads with ashes — the sign of Christian repentance.

These and other welcoming initiatives have begun to make a difference. In June, Herz-Lane reported that attendance at Sunday services was averaging 529 people — up 27 percent — on Sunday. To beef up the worship experience, he hired Pugh as associate pastor and a 20-something director of contemporary music.

Now he is launching a capital campaign to upgrade the church’s traditional and contemporary worship spaces with state-of-the-art audio-visual technology to accommodate the needs of a younger generation.

“People are pretty enthusiastic,” Selgrade said. “Change is always tough. And there have been some bumps in the road, but things are going pretty well.”

[ad number=“3”]

‘It’s not just about feeding hungry people’

While outreach and invitation may help the church grow, other parts of Herz-Lane’s vision may be more difficult to implement.

In September, Herz-Lane notified the church council that he planned to officiate at a same-sex marriage in Charlotte. Pugh, an associate pastor, performed one such marriage before coming on board.

Herz-Lane now wants the church to declare itself a “reconciling” congregation, meaning that it is welcoming and accepting of LGBTQ people.

Some 762 ELCA churches, seminaries and campus ministries — about 8 percent of its institutions — have formally adopted a welcome statement, and another 434 are in the process, according to Reconciling Works, a Lutheran advocacy group.

Herz-Lane said he expects such a measure to pass since the denomination already allows LGBTQ people to serve as clergy, and in 2015 ruled that congregations may decide for themselves whether to marry gay and lesbian couples.

Nathan Sliwa, the newly appointed minister for contemporary music, and a gay man, is banking on it.

“Before I took the job, I went to the pastors who were hiring me and asked them, ‘Are you ready for whatever potential backlash may happen from me being hired?’” he said. “They reassured me they would go to bat for me if anything happened.”

Perhaps more controversial, church leaders want the congregation to take on more of an advocacy role. For years it has had an active social ministry, providing food, clothing, housing, and other forms of assistance to those in need, in Cary and across the world.

Now they want to start a local chapter of a national community-organizing network, the Industrial Areas Foundation, which could advocate for such things as health care, green energy, criminal justice or immigrant rights.

“It’s not just about feeding hungry people and collecting food for the food pantry, as important as that is,” said Herz-Lane. “It’s also important to look at systemic injustice so people aren’t hungry in the first place.”

But so far, the church has tended to shy away from taking stands that could be construed as political. After President Trump issued a travel ban in his first days in office, Herz-Lane, posted a statement to Facebook saying, “What happened to this country I fell in love with 40 years ago?” Some people bristled and told him he was being political.

But the biggest challenge may be attracting diverse and multicultural young adults without alienating older ones.

Like many mainline churches, membership at Christ the King skews older. Most church members are 50 and up, and the percentage of millennials is tiny.

“We’ve neglected young adults and anybody from the age range of 18 to 32, especially if you’re not married and don’t have kids,” said Sliwa, who at 24 is one of just 20 younger members.

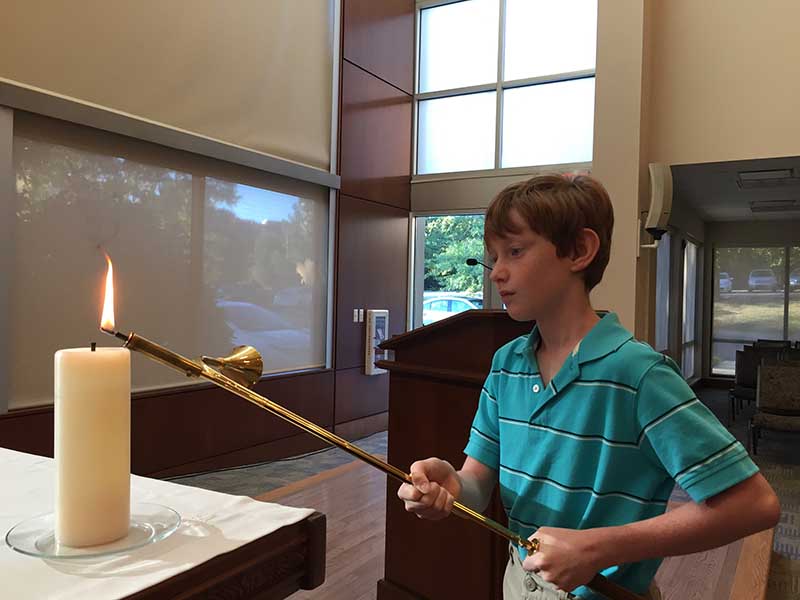

Zachary Shultz, 10, lights the candle on the altar at the beginning of church services at Christ the King Lutheran Church in Cary, N.C. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Earlier this month, church leaders were invited to attend a workshop at Fuller Theological Seminary’s Youth Institute in Pasadena, Calif., on strategies for better engaging teens and emerging adults. After trying some new approaches, they will return to Fuller in March to talk about what worked.

Meanwhile, the church is concluding a yearlong series of events tied to the anniversary of the Reformation. It includes watching a documentary, reading a book and participating in a joint worship with the bishop of the local Catholic diocese.

Herz-Lane hopes members gain a deeper appreciation for Luther’s willingness to break the mold and try new things.

“We’re here for the sake of the world, not to preserve some silly tradition,” he said. “A lot of churches don’t get that.”