(RNS) — Even before the Museum of the Bible opened nearly a year ago, many Americans knew of its evangelical founders, the billionaire Green family.

In 2014, the Greens’ company, the arts-and-crafts giant Hobby Lobby, had successfully sued the Obama administration, in a case decided by the Supreme Court, to free Hobby Lobby from an Obamacare mandate to provide employees free access to birth control.

Some said the case confirmed their suspicions that the museum, located just south of the National Mall, was intended to advance the evangelical view that American government should be based on biblical foundations.

Not all of the criticism was political. As the opening approached, Hobby Lobby faced questions about the problematic origins of some of the company’s antiquities, including a $3 million federal court settlement over its purchase of clay artifacts from present-day Iraq.

Most persistently, critics said the museum privileged the Protestant Bible over other versions, particularly the Hebrew Bible.

But much has changed in a year at the $500 million museum, still chaired and largely supported by Steve Green. As its first anniversary approaches, it has announced the appointment of a new chief executive, a new chief operating officer and a new chief curatorial officer.

Rena Opert is the new director of exhibits at Museum of the Bible in Washington. Photo courtesy of Rena Opert

And two months ago, it quietly hired a director of exhibits — a Jewish woman who was recruited away from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where she was in charge of traveling exhibitions.

Neither a curator nor a Judaica expert, Rena Opert will work on strategic planning — scheduling temporary exhibitions and directing them from concept to completion.

Still, her hiring, which has yet to be announced on the website, is symbolic of the direction the museum says it is committed to: presenting an inclusive view of the Bible, communicated through cutting-edge technology that accurately represents the multitude of ways the Bible has affected civilization.

“I know there are a lot of assumptions about what this is about,” said Opert, 39, referring to the museum. “But I do think they really want to be open and invite everybody to come and engage with the Bible and have diverse audiences. I haven’t seen evidence of an agenda.”

Opert points to a number of exciting exhibits on the horizon: a joint exhibit with the National Museum of African American History and Culture around a “Slave Bible” owned by the historically black Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn.; an exhibit of German artist Willy Wiedmann’s illustrated Bible in an accordionlike format that stretches a mile long; a spring exhibit of Passover Haggadahs, the Jewish text that recounts the Exodus story, from medieval Amsterdam.

Though she has spent her entire career in Jewish institutions — prior to working at the Holocaust Museum, she worked at Chicago’s Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership — Opert said she was recruited because of her interest in cultural property, the laws governing who owns art and antiquities.

For several years she co-taught a class at the George Washington University with Thomas R. Kline, a lawyer and authority on Holocaust-related art claims. The Museum of the Bible retained Kline last year as a consultant to help ensure that it properly reviews the provenance, or origins, of the items in its collection. (This summer, the museum announced it was returning a medieval New Testament manuscript to the University of Athens after learning it had been stolen.)

It was Kline who introduced Opert to Jeffrey Kloha, who was hired earlier this year as chief curatorial officer. In an email statement, Kloha said Opert has already “refined and strengthened our procedures and policies and helped with long-term planning for exhibits.”

For Opert, who described her position as her “dream job,” the opportunity was tantalizing.

“They’re not just looking for people from one perspective,” Opert said. “They’re really looking to diversify and bring in museum professionals and people from different backgrounds. People have been incredibly respectful and open to that and wanting to hear these voices.”

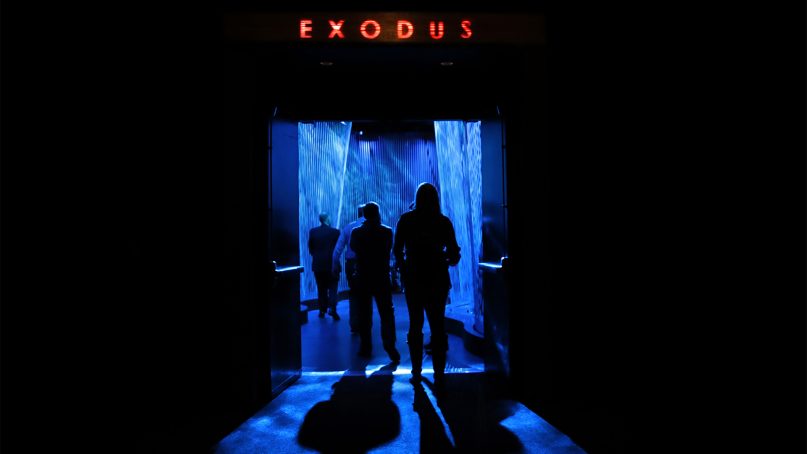

Visitors explore the Museum of the Bible, in Washington, in late 2017. Photo by Alan Karchmer/Museum of The Bible

Still, within the Jewish community and among a group of biblical scholars, the museum continues to get mixed reviews. Scholars Candida Moss and Joel Baden wrote a book, “Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby,” in which they concluded that the Green family that founded the museum brings a “fundamentally anti-intellectual orientation” to the endeavor, one rooted in the family’s evangelical understanding that the Bible is true and without error.

More recently, Moss, a theology professor at the University of Birmingham in England, and Baden, a professor of Hebrew Bible at Yale Divinity School, suggested the museum is exploiting Jewish tradition by buying thousands of mostly decommissioned Torah scrolls, restoring them and then donating them to charitable institutions and reaping a huge tax write-off.

“I’m not impressed by who is hired or who is named,” said Baden. “I want to see what they’re actually saying and doing. It’s unclear to me that they have made changes or are even interested in making changes or even recognizing the problems that are relatively straightforward and require changes.”

To Moss, Baden and other scholars, such as Jill Hicks-Keeton of the University of Oklahoma, the museum presents Judaism as a steppingstone for Christianity rather than a religion in its own right; it laid the groundwork for the true and more complete faith — Christianity — to emerge.

The Jewish members of the museum’s own advisory board, some of whom have signed agreements not to criticize the museum, dispute this. They say they are working diligently to fix errors or inaccuracies in the presentation of Jewish material and are now helping guide museum docents to be more inclusive and open toward the Hebrew Bible and the Jewish faith.

“The advisers are constantly coming up with better ways to do things,” said Lawrence Schiffman, professor of Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University. “But the point I’m making is, this is a healthy kind of discussion that people have to have in refining a museum, which took upon itself a very difficult task.”

Schiffman, who, like the rest of the advisory board, is paid, flatly denies accusations that the museum’s presentation of Jewish issues is “supersessionist,” referring to the traditional Christian belief that Christianity is the fulfillment of biblical Judaism.

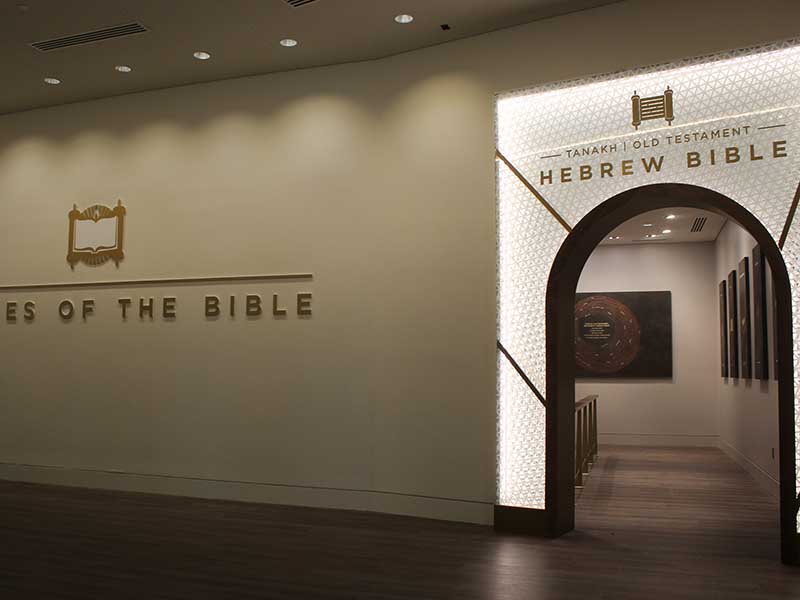

He and others point to multiple exhibits of Jewish material in the eight-story, 430,000-square-foot museum, including a mammoth exhibit of artifacts contributed by Israel’s Antiquities Authority. The semipermanent exhibit is expected to last 10 years, though the items on display may be rotated.

The museum also has an immersive Hebrew Bible exhibit complete with a special-effects burning bush. It hired a Jewish scribe to write a Torah scroll on site at the museum. Rabbi Eliezer Adam engages with visitors about his work as he writes his parchment scroll. The museum even has some kosher food in its terrace sixth-floor restaurant, Manna.

Rena Opert, the new director of exhibits at Museum of the Bible, poses with pallets as temporary exhibits are switched in Washington. Photo courtesy of Rena Opert

And while some of the Jewish press pilloried the museum — The Forward’s review “We Went To The Museum Of The Bible — So You Don’t Have To,” a case in point — others have been mostly positive.

“Washington’s new museum makes an invaluable contribution to American (and Jewish) cultural literacy,” wrote Diana Muir Appelbaum in the Jewish magazine Mosaic.

Eric Meyers, professor emeritus of Judaic studies at Duke University and an adviser to the museum, said he would like to see the museum undertake a research project into the hundreds of Torah scrolls rolled up and stacked horizontally behind a large glass wall in the museum. Once they are fixed, he’d like to see some donated to Jewish communities that need them.

“That’s a major discussion that’s ongoing and needs some kind of positive resolution,” he said. “That’s a sore spot with me and I’ve been upfront about it.”

But he sees the hiring of Opert as a positive step forward in making the museum more pluralistic and open to people of all faiths.

Opert, who defines her faith as “traditional” and said she attends synagogue but is not Orthodox, said her experience so far has been very encouraging.

“There’s a lot going on here,” she said. “The talk is about ‘What can we do to make this place great? What exhibitions do we want to bring in? How are we going to work on that?’ There are people here from a variety of backgrounds. Nobody is proselytizing to me. Nobody’s asked me even about my religion.”

Entrance to a section about the Hebrew Bible at Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 1, 2017. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks