(RNS) — As COVID-19 has resulted in bans on religious gatherings in many houses of worship, donations have collapsed. Many churches will be forced to reduce overhead, and some will close. Congregations that are rethinking their finances right now need to know that it’s possible to have a bright future with a part-time pastor.

I’m not suggesting that churches regard the pastor’s salary as the first place to make a cut; other, less consequential economies may be enough to keep most churches in business. But if salary cuts are needed to keep the doors open, I am here to give churches hope.

Some will resist, fearing that part-time clergy portends less effective ministry and only more decline. But my research for my new book on part-time ministry shows that a pastor whom a small church can afford — coupled with laity who go from being religious consumers to well-coached practitioners — can mean more vitality, not less.

Take, for example, Christ Episcopal Church in Bethel, Vermont. In the 1990s, Christ Church had a full-time priest, but its members knew they faced some tough choices. With just a couple dozen attending worship most Sundays, the congregation struggled to muster a full-time compensation package. Further, Christ Church maintains not one but two houses of worship — one in downtown Bethel and a predecessor, six miles away, that dates to the 19th century. Though the congregation only meets at “Old Christ Church” in the summer, parting with this historic legacy was more than members could stomach.

Christ Church found revival, both financially and spiritually, by switching to part-time ministry. After first sharing a priest with another congregation, Christ Church moved to unpaid part-time clergy when a parishioner got ordained while keeping her day job as an insurance agent. Freed from the strain of funding salary, insurance premiums and retirement benefits, the church has been able to do much-needed building renovations while kicking in about $1,000 annually to the Bethel Food Shelf, an anti-hunger ministry the church couldn’t afford to participate in before, according to the church’s senior warden, Nancy Wuttke.

Christ Episcopal Church in Bethel, Vermont, maintains two houses of worship, meeting in “Old Christ Church” during the summer. Photo via EpiscopalChurch.org

Every congregant has taken on at least one area of ministry responsibility, meaning everyone is more engaged than ever.

“It’s up to us to keep the church alive,” says Katie Runde, an artist and musician in her 30s who joined the church a few years ago and is now in training to become another unpaid priest at Christ Church. “In some ways, it’s more alive because every member is active.”

What happened in Bethel points to what’s possible for a giant, growing and underappreciated swath of the American religious landscape. A whopping 43% of U.S. mainline Protestant congregations have no full-time clergy to call their own, according to preliminary data from the not-yet-released 2018-19 National Congregations Study. That’s more than 26,000 local churches.

Christ Church Bethel was helped by Episcopal tradition, which allows for empowering laypeople from a church’s own ranks for effective ministry. Its first unpaid part-time priest, the Rev. Shelie Richardson, traveled a custom education path with guidance from the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont’s Commission on Ministry.

In 2017, the congregation raised up another laywoman, Kathy Hartman, to help carry the load, but even before Hartman was ordained, the congregation mobilized to share pastoral duties to make sure no one got burned out. For example, rather than require the clergy to prepare a sermon every week, half the congregation comprises a de facto preaching corps and members take turns in the pulpit.

Other work is also shared. Members have put their talents to work rebuilding stairs and doing other construction projects. Those with a flair for decorating gave the parish hall a makeover, adorning walls with spirited, uplifting art in formerly sterile spaces. Most say they would have been too shy to show such initiative with the presence of a full-time priest.

Now, at meetings of the church’s governing board, or vestry in Episcopal parlance, the atmosphere is joyful. Meaningful decisions and open discussion are led by a positive, high energy lay leader. Laypeople have taken a large measure of control and are not looking back.

“If we were given some big chunk of money now, we would do more repairs on Old Christ Church,” Wuttke says. “I don’t think it would even occur to us to say, ‘Oh, you know what, we could probably afford a priest now.’ Having a paid priest would probably free us up to do other things, but I don’t know that we want to be freed up. We kind of enjoy feeling like we’re needed and supporting each other.”

If Christ Church can do it with unpaid clergy, imagine what’s possible for the thousands that are able to pay pastors for 10, 20 or 30 hours a week.

One key to making a part-time pastorate like this work is to be upfront about the parameters of the job and sticking to them. It does not mean finding a clergyperson who’s independently wealthy and treats the ministry as a meaningful hobby. Nor should a congregation exploit one who is willing, perhaps due to weak boundary-setting skills or an inability to say no, to put in full-time hours for part-time pay. Such arrangements too frequently lead to burnout and resentment.

A congregation that ignores limits on a part-time pastor’s time or winks dismissively at the idea of ministry being part time disrespects the pastor’s capacity to earn outside income or pursue other priorities.

Instead, the door to vitality opens when laypeople say: “We can do this. We can rethink the pastorate and take on pivotal ministries that used to be our pastor’s job.” As congregants imagine that future and live into it, they channel grace and impact lives visibly, including their own.

Planning can make a big difference. Most congregations sort of fall into part-time ministry after pivoting — or panicking — when the money gets tight and a new model is urgently needed. This is understandable: Ailing congregations are often bombarded with warnings to keep their full-time pastor at all costs. They don’t map out how the congregation’s priorities will be sustained in a new organizational structure. They avoid hard decisions about what will be discontinued to make way for the new. The congregation instead scrambles to fill gaps, even if the process doesn’t make much strategic sense.

Congregations that thrive in part-time ministry often dare to think differently. They start by believing, based on biblical revelation and empirical evidence, that part-time ministry doesn’t have to be their downfall. Rather, they see how it might usher in a new slate of opportunities for maturity and growth.

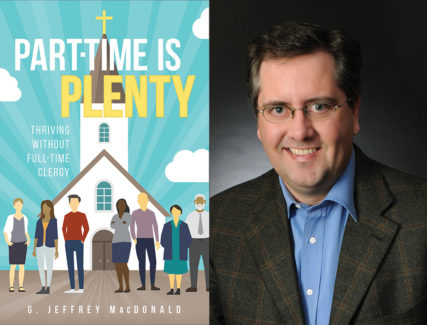

“Part-Time Is Plenty: Thriving Without Full-Time Clergy” and author G. Jeffrey MacDonald. Courtesy images

Once they’ve decided to go part time, they give themselves a good 18 months to fine-tune game plans and lay groundwork. That provides time for congregational discussion on how best to use the pastor’s time, how pastoral responsibilities will reduce or be reallocated and how expectations – both in the parish and in the wider community – can be calibrated to support success. This foresight gives a congregation a sense of control over its destiny.

For those that have already waited beyond an ideal transition point: Fear not. Congregations that delay might need to pare the pastorate more substantially or mobilize laity more assertively, but none of that is inherently fatal. They can still tap fresh lifeblood if they rise to the occasion by opening their minds to the new thing God is doing in their midst and hop on board.

(G. Jeffrey MacDonald is a religion reporter and a part-time United Church of Christ pastor. This commentary is adapted from his book “Part-Time Is Plenty: Thriving Without Full-Time Clergy.” The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)