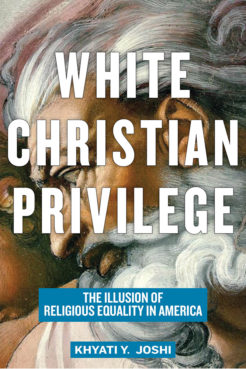

(RNS) — The image of President Donald Trump standing in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church holding up a Bible perfectly encapsulates the point of Khyati Y. Joshi’s new book, “White Christian Privilege: The Illusion of Religious Equality in America.”

In the United States, one religion is more equal than others.

Joshi, professor of education at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Teaneck, New Jersey, argues that while America offers religious freedom, true religious equality is a myth.

In every way, Christianity, especially of the white Protestant variety, undergirds the nation’s institutions and practices. Other faiths are seen as abnormal or unusual.

Christian privilege, she argues, led to “In God We Trust” being printed on every dollar bill since the 1950s. It allowed the Supreme Court in the 2014 case of Town of Greece v. Galloway, to permit volunteer chaplains to open public meetings with sectarian prayer. And it inspired the president to stand before a church and hold the Bible in his right hand for a photo op, moments after the area was cleared of protesters demanding racial justice.

Joshi, who is Hindu and grew up in Atlanta as the daughter of Indian immigrants, has spent her life studying different faiths. She earned a master’s degree in theological studies from Emory University’s Candler School of Theology and did postgraduate work at Hebrew University in Jerusalem before earning a doctorate in education from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Khyati Y. Joshi. Courtesy photo

One chapter in her book explores the historical effects of the 16th-century papal document “The Doctrine of Discovery.” That decree authorized Christian monarchs to claim any land not owned by Christians — a doctrine she argues was used to justify the conquest of Indigenous people in the United States. And she argues slaveholders spread a version of Christianity designed to make slaves more docile and loyal.

Joshi’s book weaves together stories of Supreme Court cases throughout American history that privileged Christianity with her own personal stories of harassment and discrimination. By doing so, she shows how religious tolerance and racial equality are more aspirational than real.

She points to treatment of Muslims and Sikhs post 9/11, when anyone with brown skin, beards, hijabs or turbans was targeted for heightened security screening at airports, if not outright violence. She mentions the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where white supremacists shouted “Jews will not replace us,” as another example.

But white Christian privilege is also more subtle, as when public schools don’t recognize the religious holidays of its minority students, or when sports coaches pray to Jesus before athletic competitions regardless of the faith of team players.

Religion News Service spoke to Joshi from the New Jersey home she shares with her husband, John Bartlett, and their teenaged son. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

What was it like to grow up as a Hindu in Atlanta?

It was both about being Hindu and brown. It’s hard to separate. White people didn’t know what to do with me. I faced a fair amount of harassment and bullying in middle school and high school around my racial and religious identity.

I know the stereotypes that developed from National Geographic were why students asked, “Oh, do you have your own pet elephant?” The sad thing is, teachers didn’t intervene. You can draw a straight line from those experiences to why I’m in teacher education for 20 years. I do workshops in the real world with teachers and administrators. Folks need to understand our biases and privileges because it impacts kids’ education.

How did the idea for this book develop and who is it for?

“White Christian Privilege: The Illusion of Religious Equality in America” by Khyati Y. Joshi. Courtesy image

For the last 10 years, I’ve been doing a lot of public talks on the intersection of race and religion. Whenever I started sharing these ideas, people were really interested. I talk about Christianity’s role in the construction of whiteness and white supremacy in the United States. Folks were engaged. There’s a burgeoning literature about whiteness in the last seven, eight years. But Christianity’s role in that construction wasn’t given the importance it should. And when Christianity and whiteness was talked about, it was only vis-a-vis racism in the church. It was a black-white conversation. Asian-American Christians and Hispanic Christians are left out of that conversation.

The book is intended for multiple audiences. It’s for Christians, as a way of giving them some language to see what’s going on. It’s for religious minorities to also give them language to articulate their experience.

You write about the idea that there is equal religious freedom in the United States as an optical illusion. Explain that a little.

An optical illusion prevents you from seeing what’s in front of you but it also distorts what you’re looking at. It appears to be something else. A lot of people think, because we have freedom of religion enshrined in our First Amendment, we’re good to go.

All religions have freedom of religion equally.

That’s not true.

Once freedom of religion is in people’s minds, it almost becomes invisible and the focus falls on race. But Christianity has been right there all along. That’s the optical illusion we get. We are not able to fully see Christianity’s role in the construction of whiteness and the impact of race and religion have together in society.

Isn’t it inevitable that Christianity has shaped America’s laws, customs and habits? How could it be otherwise?

Yes, but we have to be able to see that’s what’s going on, instead of having the illusion that we’re a religion-neutral society. That’s the myth I’m trying to bust. It’s not about framing what’s good or bad. It’s about seeing what’s there and working for justice.

That’s the thing about Christian privilege and Christian hegemony. It’s not going to always be very obvious to folks. Once you can see it, you’ll see it in many different places.

The courts will talk about being facially neutral. But they’re not neutral.

How do we as a society make things fairer for minority faiths?

First and foremost is making the invisible, visible. It’s really about seeing things in a different light.

My whole life I got questions like, “What’s your Bible?” “What’s your Christmas?” And I’m like, I don’t have one scripture. Are you asking what’s the most significant Hindu holiday? Reframing questions that don’t work from a Christian norm.

If you understand institutional racism and institutional religious oppression, then you understand privilege much better. If we get people to understand that, they’ll bristle less.

I’m in an interfaith marriage. We’ve raised our son to be both Hindu and Episcopalian. We have lived our lives in a very interfaith way. When I’m fasting for Shivaratri, which is the birthday of the Lord Shiva, John fasts for Shivaratri. We do everything together.

A couple of years ago, our church had a feast for Thanksgiving. I signed up. One of our local Hindu temples was having its Diwali dinner on the same Sunday night. My husband is a county commissioner. The local temple reached out to John. He agreed to do that. That Sunday the Hindu went to church, and the Christian went to the Hindu temple for Diwali celebration. That’s symbolic of our lives.