(RNS) — On Feb. 16, 2021, longtime fans of gospel and contemporary Christian music mourned the death of Carmelo Domenic Licciardello, known to his fans as “Carman.”

Christianity Today, Religion News Service and Relevant described Carman as a show-stopping misfit in the contemporary Christian music world. Indeed, in terms of his musical style, the niche Carman occupied on Christian radio was small; it consisted of himself.

Carman may have stood out from his CCM peers, but his over-the-top glitz and glam were right at home in Pentecostal televangelism. And, as a troubadour of the Pentecostal celebrity set, he made an enduring impression on the evangelical landscape.

RELATED: Carman, Christian music icon and Gospel Music Hall of Famer, dies at 65

Carman’s initial dreams of stardom were in musical theater, and Pentecostalism was a form of Christianity that allowed his penchant for theatrical storytelling to flourish. As historian Arlene M. Sánchez-Walsh has noted, “Pentecostals tell great stories.” Accounts of wayward daughters and sons on the road to perdition meeting God and experiencing a “come-to-Jesus” moment are the crux of Pentecostal revival preaching, teaching and music.

As he told his own conversion story, for Carman, the road to revival was long and winding, full of thrills and chills. It included a fledgling music career in New Jersey casinos that brought him uncomfortably close to a crime family linked to extortion and racketeering. Carman’s story also included a pivotal moment at Disneyland, where he heard the music of Andraé Crouch, a Black Pentecostal reared in the Church of God in Christ. That day, at the “happiest place on earth,” Carman resolved the cosmic question about his soul’s final destination and began to create a distinct form of music and art that, like him, defied neat categorization.

Carman performs in an undated photo. Photo courtesy of Hoganson Media Relations

Throughout his career, Carman was a Pentecostal showman. While other CCM artists in the 1980s and 1990s imitated the sights and sounds of rock bands and pop icons, Carman’s performances resembled those of popular televangelist preachers like Jimmy Swaggart and Bishop Carlton Pearson.

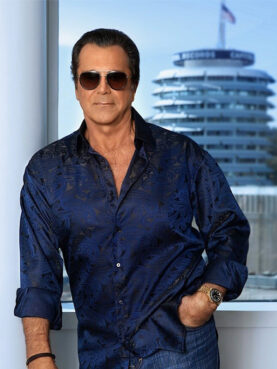

Carman embodied a stage persona that adopted and subsequently adapted a particular Pentecostal aesthetic and embraced Disney levels of cartoonish imagination. He relished his role as a broadly stereotypical Italian American and playfully nodded to the gentleman’s swagger of the 1950s Rat Pack and the contemporary masculinity demonstrated by cinematic characters like Rocky Balboa.

Carman may be best described as a Frank Sinatra-like figure who came to know Jesus through the music ministry of Andraé Crouch and rose to popularity in the interwoven thicket of televangelist Jan Crouch’s perfectly coiffed pink tresses and Paul Crouch’s garish television sets.

Nothing characterized Carman’s Pentecostal identity more than his hit song and music video “Revival in the Land.” Dressed impeccably in a pinstripe suit, Carman narrated a supernatural story to a packed audience. In it, Satan talked with a recently maimed imp (in an elaborate costume and voiced by Carman) during a prerecorded video aired during a live concert event. The dialogue, set in hell, was a flash survey of 1990s Christian ethics from a fundamentalist perspective (anti-abortion, pro-prayer in public schools, anti-New Age religion, etc.).

RELATED: Cancer diagnosis gives second life to Carman’s music career

Carman’s Pentecostal proclivities then came to the fore as Satan and his minion began to tremble. Satan may have won a few battles, Carman rap-sings to the crowd, but through the prayers of the “sanctified, tried blood-bought, spirit-filled, saints of God actually presently on their knees in prayer” the saints of God were destined to win the war. Carman’s revved-up audience — identified by Satan’s minion as “holy terrors” who bind and cast out demons, do the “charismatic jig,” quote Scriptures and pray for revival — were the source of demonic fear.

Carman’s consistent presence as a top-seller in CCM charts demonstrated that his militaristic and triumphant depiction of American Christians as a “sleeping giant called the church (to) rise up with power” was welcome in evangelical circles. Indeed, evangelicals formed by the heaven-and-hell dualisms of the likes of Billy Sunday and Billy Graham loved the spiritual warfare elements of Carman’s music arguably as much as their Pentecostal counterparts.

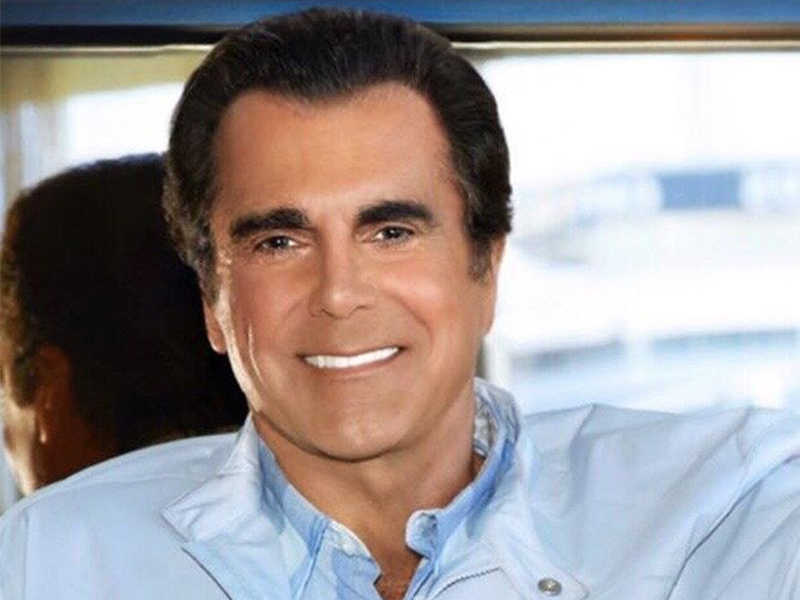

Carman died Feb. 16, 2021, at the age of 65. Photo by Mario Barberio, courtesy of Conduit Media Solutions

Through the art of Pentecostal storytelling, Carman cast the church (evangelical and Pentecostal teens especially) as warriors battling against darkness and messengers proclaiming light, truth and divine retribution. Capitalizing on the fear and fervor of the “satanic panic” of the 1980s and 1990s, Carman’s cinematic stylings were a call to arms, and evangelicals responded with enthusiasm.

“A Witch’s Invitation,” clearly indebted to Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” warned anxious evangelicals to fight with prayer the metaphysical evil that lurked behind material objects like pentagrams, horoscope signs, ouija boards and Dungeons & Dragons games.

Part of what made Carman seem so weird was that he didn’t try at all to make Pentecostal flamboyance palatable to his audience. Throughout the 1990s, Carman was a regular guest and host on Trinity Broadcasting Network‘s flagship program, “Praise the Lord.” TBN was founded by Paul and Jan Crouch, two Assemblies of God media moguls who trafficked in an unapologetically ostentatious Pentecostal aesthetic.

Carman’s friendship with the Crouch family afforded him production opportunities that included music videos, full-length concerts and a film called “Carman: The Champion.” Over the years, TBN welcomed a who’s who of American charismatic and Pentecostal celebrity subculture, including Juanita Bynum, Jesse Duplantis, Creflo Dollar, Kenneth Copeland and Paula White. Carman was at home among these media makers who made sure every hair was in place, their sartorial choices loud but impeccable, their skin tanned or contoured to perfection.

Carman’s Pentecostal celebrity glam and televangelist flair did not put off his youngest fans. Indeed, his imaginative spiritual battles were embraced most heartily by children whose parents may have forbidden Dungeons & Dragons, but were fine with the demon-slayer Carman. He was eulogized poignantly and humorously on Twitter by nostalgic youth group alumni who had grown up with his music played in the lock-ins, jamborees and revivals of the 1980s and 1990s. For many of them, Carman’s free (pay by donation) concert was their first live show.

“Tried to explain Carman to someone who didn’t grow up in the church,” tweeted one fan of Carman’s one-of-a-kind status, “and it felt like I was a member of Q-Anon for the duration of that conversation.”

“It was hard to hear that my childhood hero, Carman, passed away,” wrote another. “Like every youth group with any credibility we toured churches with our performance of his masterpiece, ‘The Champion.'”

In the end, Carman’s lasting contribution may have been introducing a fantastical and triumphant Pentecostal world to a generation of young evangelicals. His songs were playful and magical. Scary, yes, but Disney scary. The demons were sure to be vanquished by the end of a novelty song. His productions were horrific and grotesque but ultimately had a triumphant conclusion.

“It might feel like Friday night,” he sang famously, “but Sunday’s on the way.”

(Leah Payne is associate professor of American religious history at Portland Seminary. She is writing a book on how CCM shaped evangelicalism in the U.S. and is collecting surveys from listeners on the CCM Survey. Dara Coleby Delgado is a theologian and historian of American religion. She is assistant professor of religious studies and Black studies at Allegheny College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)