(RNS) — Visceral. Provocative. Challenging. Offensive. Sacrilegious.

All these words have been used — in praise and criticism — to describe the newly released video for rapper Lil Nas X’s single “Montero (Call Me by Your Name)” since it first aired Friday (March 26).

Beginning in the Garden of Eden, the video depicts Lil Nas X (real name: Montero Lamar Hill) as fallen angel being tempted by demons and judged in heaven. He then descends to hell on a seemingly endless stripper pole, where he greets Satan with a lap dance, before snapping the devil’s neck, taking his “crown” and growing angelic wings.

The video is both social commentary and an artistic statement on the rapper’s identity and sexuality.

RELATED: Conspiracy theories and the ‘American Madness’ that gripped the Capitol

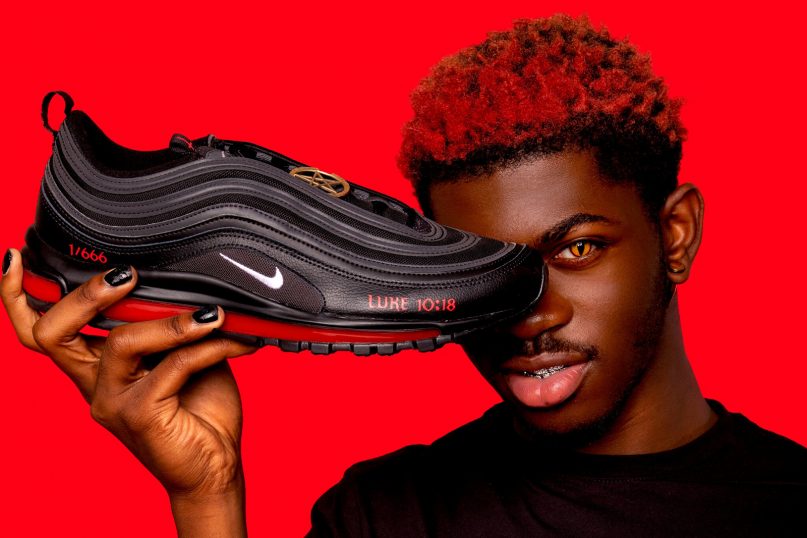

In conjunction with the song’s release, the Brooklyn, New York, art collective MSCHF modified 666 pairs of Nike Airs with pentacles and injected them with a red liquid reported to contain a drop of human blood, dubbing them “Satan Shoes.” In 2019, the same collective released “Jesus Shoes,” allegedly injected with holy water.

Nike has since disavowed any connection to the Satan Shoes and is suing MSCHF, alleging trademark infringement.

The cultural backlash was as immediate. Conservative author and talk show host Candace Owens, in a tweet Sunday, suggested that Lil Nas X was being used by corporations to “destroy our youth.”

South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem tweeted: “We are in a fight for the soul of our nation. We need to fight hard. And we need to fight smart. We have to win.”

Others, including the singer’s fans and many in the LGBTQ+ community, felt the video was daring. The sneakers reportedly sold out in one minute. One pair went to Miley Ray Cyrus, who tweeted a picture of herself wearing them, saying, “Can you see Satan?”

The Church of Satan, an organization founded in 1966 by Anton LaVey, approved as well. “The video is a visceral and powerful work clearly celebrating freedom, individualality, and man’s carnal nature. You deserve all the paise you’ve been receiving,” read the church’s tweet.

The Satanic Temple, a different organization based in Massachusetts, did not respond to the video, but its co-founder Lucien Greaves did tell Religion News Service that he frankly does not understand why the video has garnered so much attention. “I do not feel that it is my place to comment on the artist’s intent.” He said that he personally is neither offended by nor is he endorsing the work.

But he noted that Lil Nas X has “drawn from culturally prevalent material.”

Translation: Satanic imagery is nothing new to contemporary culture. Nor is satanic-based moral outrage.

Still from Lil Nas X’s “Montero (Call Me by Your Name)” video, directed by Lil Nas X and Tanu Muino. Video screengrab

However, true satanic panics are not typically triggered by simple things like music and shoes as with the Lil Nas X controversy. The first modern-day satanic panic, which began in the 1980s and lasted well into the 1990s, was based on unsubstantiated but widespread fears that day care workers were engaged in ritual child abuse. Pentacles were allegedly found on children’s bodies and, under pressure, children admitted involvement.

The most public day care case focused on a preschool run by the McMartin family in Manhattan Beach, California. The investigation and trial ran from 1983 to 1990, ending in acquittal. No evidence of ritual abuse was found.

But by then, the so-called satanic panic was in full swing. Stories of ritual abuse and cult activity crowded daytime television and viewer imaginations. Talk show host Geraldo Rivera is famed for his 1988 coverage of the subject. In 1991, ABC broadcast a television movie called “To Save a Child,” about a satanic cult that steals babies.

Fearful adults took aim at a variety of cultural products, attempting to “cancel,” so to speak, everything from Dungeons & Dragons to heavy metal music. Satan was seen lurking everywhere.

In 1992, FBI agent Kenneth V. Lanning released a detailed paper declaring that there was no evidence of ritual child abuse or a national satanic threat. In 1995, Rivera issued his own apology.

But while Lanning’s statement marked an official end to the panic, the moral outrage carried on, targeting Pokemon and the “Harry Potter” book series. As recently as 2019, a Catholic school banned the Potter books, alleging that the spells in the books “risk conjuring evil spirits.”

Moral panics come in a variety of forms, which are as American as conspiracy theories and anxieties about vaccines. The very first American instance resulted in the infamous Salem witch trials. Those proceedings, similar to the trials of the ’80s panic, also eventually cleared the accused of any wrongdoing, but only after 20 people had been killed.

That panic found an echo in the Red Scare of the 1950s, when fears of ungodly communism infiltrating the U.S. led to the McCarthy hearings, the addition of the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and the institution of the motto “In God We Trust.”

It was then, in 1953, that Arthur Miller penned his famous Salem-themed play “The Crucible.” A hit on Broadway, the play was, not coincidentally, only first made into a film during the satanic panic of the 1990s. After the film’s release, a New York Times reporter asked Miller about the connection between his film and the nationwide “rash of child molestation trials.”

Miller said, “I have had immense confidence in the applicability of the play to almost any time, the reason being it’s dealing with a paranoid situation.”

Would Miller say we’re experiencing another satanic panic? Before the “Montero” video, there was the QAnon conspiracy, which has been warning of a satanic cabal since its inception.

Mat Auryn, a popular witchcraft blogger and author of the book “Psychic Witch: A Metaphysical Guide to Meditation, Magick & Manifestation,” told RNS that he doesn’t believe the first satanic panic ever ended.

But Auryn, who identifies as a “queer occultist” and witch, sent his own string of tweets Saturday divorcing the “Montero” video from any accusations of satanic practice. “This isn’t some sort of QAnon illuminati conspiracy theory homage to worshipping Satan,” he wrote. “In fact, it’s the opposite — healing damage done to queer people by the Church and State.”

Still from Lil Nas X’s “Montero (Call Me by Your Name)” video, directed by Lil Nas X and Tanu Muino. Video screengrab

In Auryn’s telling, Lil Nas X’s story is an allegory of one man’s journey into his own psyche to confront his own “demons,” a spiritual practice called “shadow work.” “When he says ‘Welcome to Montero,’ that’s his name. He’s welcoming you to his mind and heart and soul. It’s significant that everyone in the video is him,” Auryn noted.

RELATED: Pagan sues Panera Bread Company alleging religious discrimination

Kenya Coviak, a modern witch in Detroit, agreed, calling this Lil Nas X’s “Lemonade” moment, referring to Beyoncé’s groundbreaking 2016 studio album. Like Auryn, Coviak adamantly held that the “Montero” video has nothing to do with satanism or any form of occult practice, for that matter.

“It was about affirming himself,” Coviak said. “It was about exposing the reality of being authentic to himself in the face of cultural condemnation.”

Coviak added that the video “is flipping off the ‘Illuminati panic’ culture of the Black Church and its view of the music industry and the existence of Black gay love being valid.”

“It is all these and so much more.”