LOS ANGELES (RNS) — The Los Angeles metro area is home to the second largest Jewish community in the United States, yet to Caroline Luce, associate director of the UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies, much of American Jewish history is dominated by a New York-centric perspective.

A new digital exhibit documenting Jewish life in the Eastside of Los Angeles aims to amplify the nuances of Jews who settled in the neighborhood of Boyle Heights. It’s a neighborhood where about 40% of its population was Jewish through the 1920s and ’30s, but it’s also where many Japanese, Armenian, Italian, Mexican, Russian and African American families settled throughout the years.

“There’s very little historical scholarship on Jewish LA,” said Luce, the exhibit’s chief curator. “We’re looking for both the influences LA had on Jewish communities … and in turn, the way those Jewish community cultural traditions influenced LA.”

The virtual exhibit, “Jewish Histories in Multiethnic Boyle Heights,” launched by the Leve Center explores the Jewish institutions that made up the landscape of this Eastside community. Its May launch coincides with Jewish American Heritage Month.

RELATED: In this Latino LA neighborhood, Jews commemorate an ancient biblical holiday

It interactively maps the synagogues, charitable institutions, schools, community centers and Jewish-owned businesses that were once located in what is now a largely working-class Latino neighborhood. It also features a timeline of Jewish history in the community. Boyle Heights is now recognized for its Chicano and Mexican identity and culture.

This exhibit builds on the Mapping Jewish Los Angeles project, developed in collaboration with the UCLA Library, that places Jews in and on LA maps “as a way of viewing their ‘place’ in the past and the ‘presence’ in events that altered the region, its residents, and its future,” according to the project. A physical exhibition, “From Brooklyn Avenue to Cesar Chavez: Jewish Histories in Multiethnic Boyle Heights,” is also housed at the Boyle Heights History Studios and Tours cultural space.

Shmuel Gonzales, a Mexican American and Jewish community historian, contributed to this exhibit by putting together background stories of the different Jewish people in the neighborhood. He explored the Hasidic history of East LA and how Jewish education came to be in the area.

To Gonzales, this online exhibit helps tell the multi-Jewish histories of LA, instead of talking about it “as a one lump kind of history.”

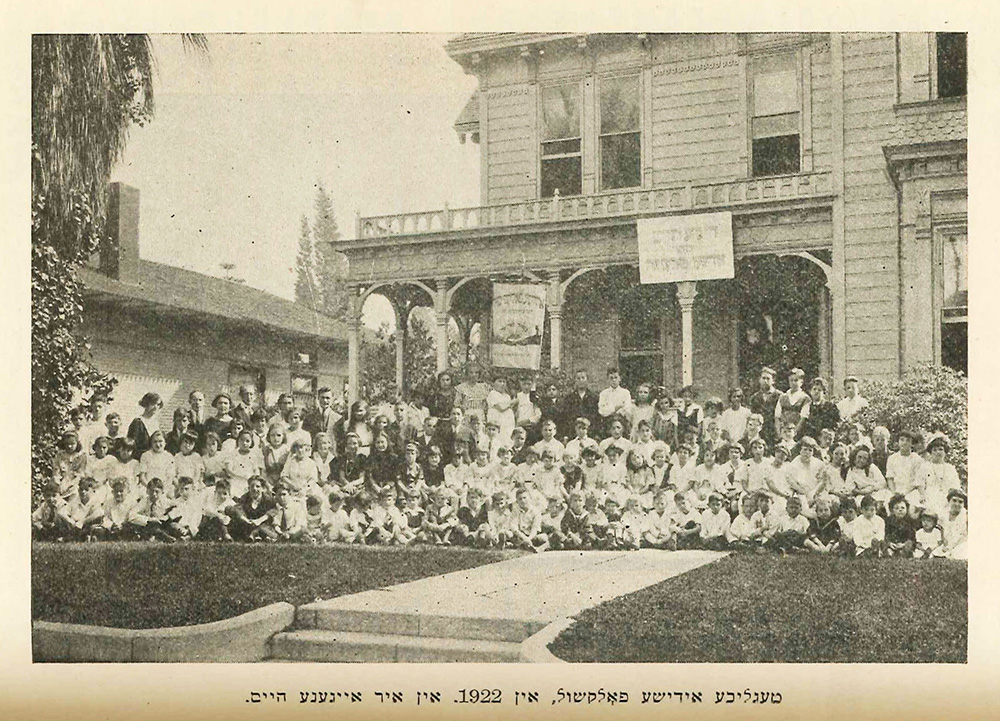

The original building at 420 N. Soto St. that housed the folkshul, in 1922. Photo courtesy of UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies

Using Google maps, the exhibit features spaces like “the folkshul,” a house in Boyle Heights that was used as a Yiddish school as well as a Yiddish cultural center and organizing space. The house also hosted meetings of local Jewish unions and labor Zionist groups, fundraisers and reading circles, according to the exhibit.

The exhibit documents how ideological conflicts arose in the space, with some parents saying that courses were “tainted by religion” and “overemphasized Jewish nationalism at the expense of cultivating internationalist working-class solidarity.” The center eventually fractured into separate communities that opened their own spaces.

The map also highlights places such as the Community Service Organization, a Mexican American civil rights organization founded in Boyle Heights in 1947, as well as the former Japanese Hospital building that served the local Japanese American community.

“Even at the moment when Boyle Heights was its most Jewish … there were just as many Mexican Americans living in the neighborhood, Japanese Americans, African Americans,” Luce said. “That’s the LA here, it’s this incredibly multiethnic context.”

Memory preservation work surrounding the Jewish history of Boyle Heights gained traction in the ’90s, after the 1987 Whittier Narrows earthquake that damaged the Breed Street Shul, the last of the Eastside synagogues that stayed open in the decades after the population shifts of the postwar era.

The Boyle Heights Victory House at the corner of Brooklyn and Soto, where various neighborhood organizations raised money to support the American war effort by selling war bonds. In 1942, the residents of Boyle Heights purchased so many war bonds that the American military named a plane in their honor, calling it “The Spirit of Boyle Heights.” Photo courtesy of Western States Jewish History/UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies

RELATED: In Los Angeles, a synagogue opens its parking lot to people living in cars

Jews in LA have a deep attachment to the neighborhood, Luce said.

But what can be problematic, she noted, is that some of this nostalgia has created a narrative of how Boyle Heights “used to be Jewish,” a “narrative of ethnic succession.”

Luce said this project aims highlight that there is not one single Jewish story, but that “there are many Jewish histories.”

For example, Luce said, there are Jews who have a deep connection to Breed Street Shul because that’s where their families attended. The synagogue’s membership reached more than 400 families with a large portion living miles away from Boyle Heights, according to the exhibit.

For other Jews, who were maybe more leftist, the synagogue represented an image of an “impenetrable” and “austere” place where the fancy people would go, Luce said. Meanwhile, other congregations, whose pattern of worship was different, may have regarded Breed Street Shul “as doing it wrong.” Then there are secular Jews, who may have not had a connection to the synagogue.

Luce said she hopes this exhibit showcases “the many Jewish histories that converged in Boyle Heights and the many different patterns of community formation, community organization, religious life that converged in this one space.”