(RNS) — Gerette Buglion did not know she was getting involved with a cult. Perhaps no one ever does.

But after nearly two decades following one man’s teachings — a man she calls “Doug” in her new book, “An Everyday Cult” — Buglion realized that somewhere along the way she had become disconnected from her own values.

“An Everyday Cult” tells the story of falling under cultic mind control and then, eventually, snapping out of it.

Since Buglion found her way out in 2014, she has had a fierce drive to share her story and help other survivors share theirs. “I feel that I am more alive,” she said. “I lost years of my contribution to society. I lost 18 years of my life to something that was allowing a cult leader to gain more traction, instead of my own light shining in the world.”

Last October, she helped co-found the #iGotOut project, which aims to inspire survivors of cultic abuse to tell their stories.

Since the site launched, it has received traffic from 74 countries and six continents. The #iGotOut hashtag has topped 11,000 mentions on social media, and others have begun using #IGotOut to spread the word.

“As a survivor, somebody who spent 15 years of my life healing from the experience of having been born and raised in a group,” said Jen Kiaba, who grew up in the Unification Church, “I’ve experienced a lot of stigma and a lot of shame that comes from larger societal misunderstandings of what people think happens to people in a cult,” she said.

When she was leaving the Unification Church, she felt no one else had been through anything similar. Now she hopes to let younger survivors know they are not alone.

Kiaba said that connecting people through their stories helps them deconstruct their experience and heal, no matter which cult they’ve escaped. She calls coercive control “almost like a cult leader’s playbook. They use the same tactics in various groups.”

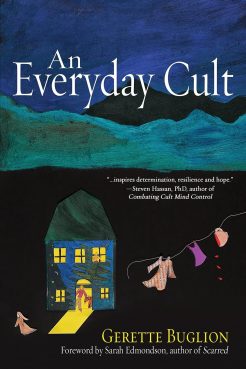

“An Everyday Cult” by Gerette Buglion. Courtesy image

Buglion’s experience started when she was a 33-year-old new mother and teacher. Her friends had begun doing what was called “the work” with Doug, and she saw an intimacy among them that she envied.

“An Everyday Cult” refers to her cult as the Center for Transformational Learning or CTL — not its actual name. Individuals’ names and locations have also been changed.

Its leader, Doug, taught that the unconscious is revealed through one’s dreams and promised spiritual growth and unrivaled insight.

At first, she said she and her husband just flirted with CTL. “I was feeling the potential and the depth of it, but I had a young child and was living my life in the world,” she said.

Buglion calls this the “falling stage” of cult involvement, noting it is similar to both falling in love or falling asleep.

It is followed, she writes, by four stages: drifting (psychological meandering), asleep, snapping awake and waking up again and again.

After falling, which she said for her spanned a five-year period, she became increasingly attached. “That doctrine was starting to replace my own personal values, my own sense of morality, my own understanding of life itself — one little chunk at a time,” she explained.

She said CTL began to take priority over her family. She remembers leaving her two children home alone so she could do CTL work.

Eventually she began paying for personal sessions with Doug. Then she abandoned her teaching career and started a cleaning business at his prompting and hired members of the group as employees. She paid Doug for business consultations. She and her husband began paying for couples’ sessions. They attended expensive CTL retreats and paid to do CTL coursework, spending so much they eventually declared bankruptcy.

“Even though I ran my own business, I was dependent on Doug, my teacher, to guide me,” Buglion said. “I was gradually becoming more and more unhinged. Then the door fell off, and the only thing that flooded in was ‘the work.’ The only thing that could help me was ‘the work.’ It became my everything.”

Gerette Buglion. Courtesy photo

Her husband pushed back, however, and after 16 years, got out. For Buglion, it took hearing about how another member of the group had been verbally abused by Doug for her to have “a sudden snapping out.”

It was the reverse of her entry into the group. “For me, it was very slow drifting into indoctrination, but also a sudden snapping out, bringing me back into alignment with my own values, my own sense of self,” she said.

Over a five-day period, she let go of something else from the group. “With each shedding, I didn’t know what a weighted cloak I was releasing, so of course I could stand up taller when I took it off,” Buglion said. “It was very profoundly empowering for me.”

She had been in the cult for 18 years, four months and 28 days.

“How can you be that far gone for that long and then so quickly snap out of it? The answer is, I don’t know,” Buglion said. “What I do know after studying cult recovery these past seven years is that it’s way less common. So far I have not met others who have that sudden end experience.”

She said that in her final years at CTL, Doug had given her more responsibilities, which in a way built up her self-confidence. In time she began to notice that although more was asked of her, leaders in the group never showed appreciation. After her husband left, followed by friends, her trust slowly split until she broke free.

Her husband’s response — “I’ve been waiting for this moment” — “is a sentence I don’t think I’ll ever forget,” she said.

Her husband then helped her begin the healing process, as did others who had left the group. They met to share their stories and insights into what they had experienced.

Having that support network, she said, was helpful but not enough. She sought out a therapist familiar with the work of Dan Siegel, a professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine and a co-founder of the Mindsight Institute, whose teaching on spiritual abuse she had listened to. In their personal sessions, the therapist was able to break down her trauma in an understandable way.

Buglion also turned to reiki massage, which she said has helped her “rewire” her brain and body.

Now, she said, she’s giving it her all to make sure cult survivors are seen and heard. She and her husband, now a licensed mental health counselor, co-facilitate a cult-recovery support group.

For the #iGotOut project, she leads a free weekly writing class called “Writing to Reckon” for those who are processing their cultic abuse through the written word. #iGotOut also promotes visual storytelling and anonymous activism, because not all cult survivors are able to publicly use their names.

Buglion and the individuals who co-founded #iGotOut, including an anonymous activist named Lisa who manages the daily website and social media, agree that bringing cult survivors together to share their stories can educate society and prevent cultic involvement.

“We all lose when others are held under by someone else’s ideas,” Buglion said. “We all lose because our creativity, our authenticity is what makes the world a beautiful place.”