LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Since protesters began toppling statues of Father Junipero Serra up and down California last summer, Catholic Church leaders have often defended the missionary, who helped to spread Catholicism and colonize the state’s Indigenous people, as a “complex character.”

Complex is also the word for the debate about what to do with the sites laid bare in the demonstrations that targeted memorials to the 18th-century Franciscan priest, who, while credited with spreading the faith on the West Coast, is also seen as part of an imperial conquest that enslaved Native Americans.

The public scrutiny of Serra — the founder of what would become 21 missions along the California coast — began as Black Lives Matter protests, denouncing institutional racism and police brutality, broke out across the country in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota last year.

Toppling of monuments honoring Confederate leaders, mostly in Southern cities, parallels demonstrations last June and July that cost San Francisco, Los Angeles and Sacramento their Serra statues. Since then, political, religious and Indigenous leaders have tried to come up with equitable solutions for their replacements.

On Sept. 24, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law to replace the Serra statue that stood on the grounds of the California Capitol since 1967 with a memorial for the state’s Native Americans.

The bill’s author, Assemblyman James Ramos, a Democrat and a member of the Serrano/Cahuilla tribe, said in a Sept. 25 statement that his goal was to replace the statue with a memorial for Native Americans in the Sacramento area. While “we do not condone the vandalism,” he said, referring to his assembly colleagues, “a more complete and accurate telling of Native history occurred” in hearings and public discussions for the bill.

RELATED: Who is Junipero Serra and why are California protesters toppling statues of this saint?

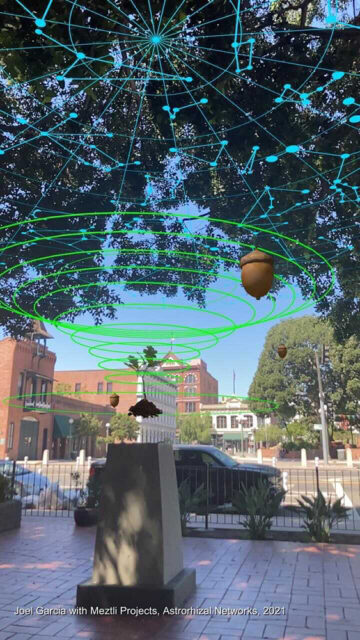

A group of people view the virtual monument through an app at the site where the Junipero Serra statue used to stand before it was toppled last June. RNS Photo by Alejandra Molina

“Native Americans have been told by others, “This is your story. This is your culture — even when the history presented to us was not what we experienced or knew to be true,” said Ramos’ statement.

Archbishop Salvatore J. Cordileone of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Francisco and Archbishop José H. Gomez, who heads the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, meanwhile, have sought a compromise that would allow Serra to continue to be recognized by Californians.

In a Sept. 12 Wall Street Journal op-ed, “Don’t Slander St. Junipero Serra,” the bishops objected to the bill’s characterization of Serra as responsible for the “enslavement of both adults and children, mutilation, genocide, and assault on women.”

The bishops asked that Sacramento’s Serra statue, which has been in storage since it was taken down by protesters last July, “be allowed to stand at the Capitol in addition to monuments to the state’s Indigenous peoples.”

What shape those monument take also has yet to be decided, as tribal nations must get approval from the legislature’s Joint Rules Committee once construction documents and plans are submitted. The monument would have to be exclusively funded privately by the tribal nations in the Sacramento region.

In Los Angeles, the archdiocese has the Serra statue in a storage facility, said Arturo Chavez, general manager of the city’s El Pueblo Historical Monument. The archdiocese asked for it when it was toppled, Chavez said.

While there are no plans to replace the statue at this time, Chavez said the city will be engaging with Indigenous leaders to discuss what could potentially take place at the site where the monument stood.

Kim Morales-Johnson, a descendant of Tongva and a Catholic, envisions a Tongva museum taking shape in L.A. Since the toppling of the Serra statue, she said city leaders have been more open to hearing about these kinds of possibilities to honor L.A.’s Native Americans.

Morales-Johnson said she’d want to work with the Catholic Church to make this a reality. “I want there to be a celebration of our culture and preservation of what we have, but also a way to honor and remember our ancestors,” she said.

Through an app, users can view the virtual monument at the site where the Junipero Serra statue used to stand before it was toppled last June. RNS courtesy photo form Joel Garcia

In the meantime, artist and cultural organizer Joel Garcia — who witnessed firsthand the toppling of the Serra statue in downtown Los Angeles — has sought to honor and memorialize L.A.’s Indigenous people through augmented reality technology.

The pedestal that propped up the statue looks bare at first glance, but once a smartphone camera is aimed toward it, an animated monument honoring the Tongva, the Indigenous people of L.A., comes alive.

On a mobile screen, an oak tree sapling radiates green rings of light, symbolizing the possibility of growth and repair. Acorns dot the sky amid a constellation of stars, as Tongva poet Kelly Caballero sings a song.

Garcia, who is of indigenous Huichol background, created the augmented reality piece as part of the “Encoding Futures: Speculative Monuments for L.A.” exhibition featuring a series of virtual monuments across the city. His “Astrorhizal Networks” installation was made possible through a residency at Oxy Arts.

The piece memorializes Indigenous concepts of time and highlights the connection between the roots, earth and sky.

“We talk about the impact of the (California) missions as it being in the past when very much what the missions have done, and continue to do to California Indians, is still very present today,” Garcia said. “This monument is about recalibrating how we look at memory and time.”

On the day of the launch, a group of people downloaded the 4th Wall, an augmented reality app featuring curated and site-specific artworks, to view the virtual installation. They walked around the bare pedestal where the Serra statue stood, viewing the constellation of stars and floating acorns as they listened to the words of Caballero, the Tongva singer and songwriter.

“Having a bunch of folks here that are using the space differently, it feels good,” Garcia said. “It feels like there’s less weight here. I think that’s part of it, too, reusing the space in a different way so that it carries a different meaning, carries different energy.”