(RNS) — When Pope Francis met recently with Nancy Pelosi at the Vatican, it put in relief the profound disagreement among Catholic leaders over how to deal with elected officials who support abortion rights.

While conservative U.S. bishops want to deny Communion to the House speaker, President Joe Biden and other pro-choice Catholic elected officials, Pope Francis and most Vatican leaders seek common ground, refuse to play politics with a sacred sacrament and don’t reduce centuries of Catholic social justice teachings to a single issue.

The previously unannounced meeting with Pelosi was just the first in a fall full of hot-button moments: The U.S. Supreme Court will soon hear a pivotal case that could dismantle the right to a legal abortion. Next week, Biden, only the second Catholic to win the White House, will have his first meeting as president with Francis while in Rome for the G-20 summit. And next month, U.S. bishops’ fall meeting will include more contentious debate over whether pro-choice Catholic politicians should be denied Communion.

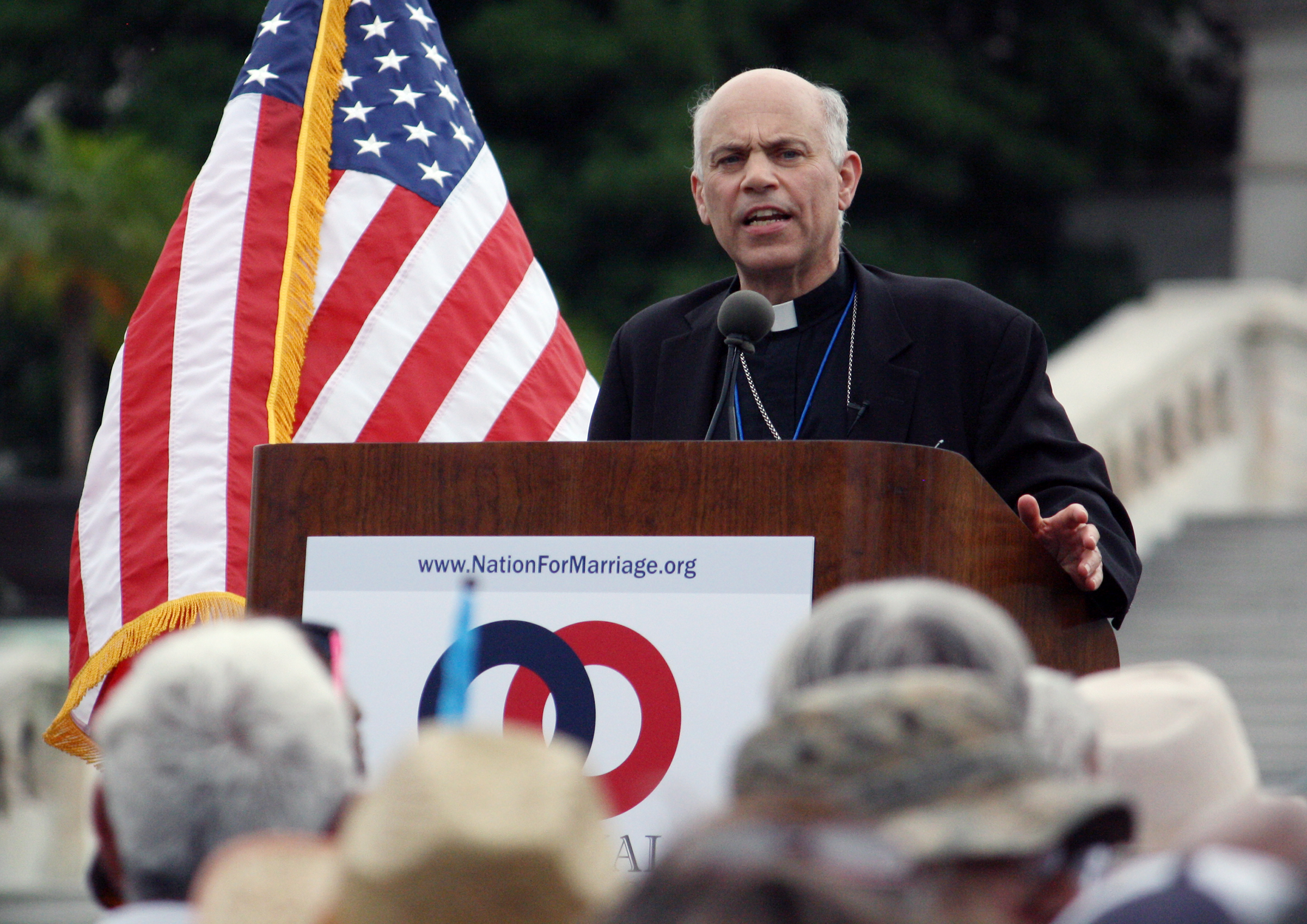

While Pelosi received a warm welcome — the speaker called it a “spiritual, personal and official honor” to have an audience with the pope — back home, the mood is strikingly different. In September, San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone published an op-ed in The Washington Post doubling down on his policy of denying Communion to pro-choice Catholic politicians, even comparing them to racist Catholics in the 1950s and ’60s who defended segregation. The piece earned praise from Bishops Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, and Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois.

Pope Francis greets U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi during a private audience at the Vatican on Oct. 9, 2021. Photo by Vatican Media

This stance is not only at odds with Francis, who has warned against turning Communion into a political weapon, but is a departure from previous popes beloved by conservative Catholics. St. John Paul II, a hero to many anti-abortion activists, gave Communion to pro-choice politicians in St. Peter’s Basilica. When Pope Benedict XVI visited Washington in 2008, Pelosi received the Eucharist during a papal Mass.

RELATED: Pope Francis meets with US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi at the Vatican

It’s worth noting that Pelosi, the longtime stalwart for abortion rights, also welcomes anti-abortion Democrats such as former Sen. Joe Donnelly — recently appointed by Biden as his ambassador to the Holy See — as part of a big-tent liberalism.

“This is the Democratic Party. This is not a rubber-stamp party,” Pelosi said in a 2017 interview. “I grew up Nancy D’Alesandro, in Baltimore, Maryland, in Little Italy, in a very devout Catholic family, fiercely patriotic, proud of our town and heritage, and staunchly Democratic. Most of those people — my family, extended family — are not pro-choice. You think I’m kicking them out of the Democratic Party?”

San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone addressed the crowd at the 2014 March for Marriage rally on June 19, 2014, in Washington, D.C. RNS photo by Heather Adams

Francis and Cordileone both oppose abortion, which the church has always declared a moral evil that ends a human life. Where Francis and culture warriors like Cordileone part ways is on the question of how to communicate the church’s position when it comes to a complicated issue at the nexus of law, morality, privacy and reproduction.

In the United States, 61% of Americans believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases. More than half of Catholics (56%) believe the same, according to the Pew Research Center. It is not surprising that people hold sincere, values-based and religious beliefs that bring them to different conclusions. Polling also finds that a significant percentage of Americans think both “pro-choice” and “pro-life” labels fail to reflect the nuances of their position.

The Catholic Church faces a major challenge convincing most Americans that ending a pregnancy is always wrong — even in cases of rape and incest. The challenge is not limited to the fact that an all-male hierarchy, which has lost moral credibility for protecting sexual predators, is not well positioned to tell women how to make deeply personal, often anguished decisions that impact their futures.

Catholic leaders also face the necessary demands of engaging in politics and public life. Their capacity to do so is imperiled by pursuing a singular strategy that leaves the church’s leaders divided among themselves and out of sync with many of its own parishioners.

Members of the the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops ride an escalator during a break in sessions at the USCCB’s annual fall meeting in Baltimore, on Nov. 13, 2017. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

This is not a new problem for bishops. After many conservative Catholic leaders erupted in outrage over the University of Notre Dame’s invitation to have President Barack Obama give the commencement address in 2009, the archbishop emeritus of San Francisco, John Quinn, articulated the dilemma well in America magazine, saying that while the bishops didn’t disagree on the moral evil of abortion, they disagreed on how to address it in public life. “And this disagreement,” he wrote, “has now become a serious and increasing impediment to our ability to teach effectively in our own community and in the wider American society.”

Quinn went on to observe:

For most of our history, the American bishops have assiduously sought to avoid being identified with either political party and have made a conscious effort to be seen as transcending party considerations in the formulation of their teachings. The condemnation of President Obama and the wider policy shift that represents signal to many thoughtful persons that the bishops have now come down firmly on the Republican side in American politics.

The reputation of Catholic bishops as Republican partisans only calcified during Donald Trump’s presidency. After many conservative bishops, activists and influential Catholic donors ignored or accommodated Trump’s racism, cruelty and contempt for democratic norms in pursuit of anti-abortion judges, the U.S. church is so diminished by self-inflicted wounds it’s hard to know who church leaders think they have the ability to persuade.

Denying politicians Communion, comparing them to segregationists and even questioning their right to call themselves Catholic are signs of desperation from religious leaders who have lost their ability to change minds and hearts.

Pope Francis speaks with journalists on board an Alitalia aircraft en route from Bratislava back to Rome on Sept. 15, 2021, after a four-day pilgrimage to Hungary and Slovakia. (Tiziana Fabi, pool photo)

During an in-flight news conference after his recent trip to Hungary and Slovakia, Francis was asked about pro-choice elected officials and Communion. He offered a road map back for Catholics who think confrontation is the best approach. “If we look at the history of the church, we will see that every time the bishops have not dealt with a problem as pastors they have taken sides politically,” he said. “When the church, in order to defend a principle, acts in a nonpastoral way, it takes sides on the political plane. What must a pastor do? Be a pastor. Don’t go condemning.”

The pope encouraged bishops to be “pastors with God’s style, which is closeness, compassion and tenderness.”

RELATED: Randall Balmer on why racism, not abortion, birthed the religious right

Bishops and other church leaders have every right to speak out against abortion and will continue to do so. But listening requires acknowledging that you have something to learn from others who bring different experiences and knowledge.

As the Catholic Church begins a period of global synodality, a process of consultation with Catholics from different walks of life, bishops should spend less time denouncing, tweeting and writing op-eds, and more time listening to people, including pro-choice Catholic women in their own pews. They will not be hard to find.

Conversations built on empathy, respect and compassion won’t quickly change the dysfunctional aspects of our nation’s abortion politics, but when we encounter each other as real people rather than simplistic cardboard cutouts representing opposing sides, that’s a good place to begin something new.

(John Gehring is the Catholic program director at Faith in Public Life and author of “The Francis Effect: A Radical Pope’s Challenge to the American Catholic Church.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)