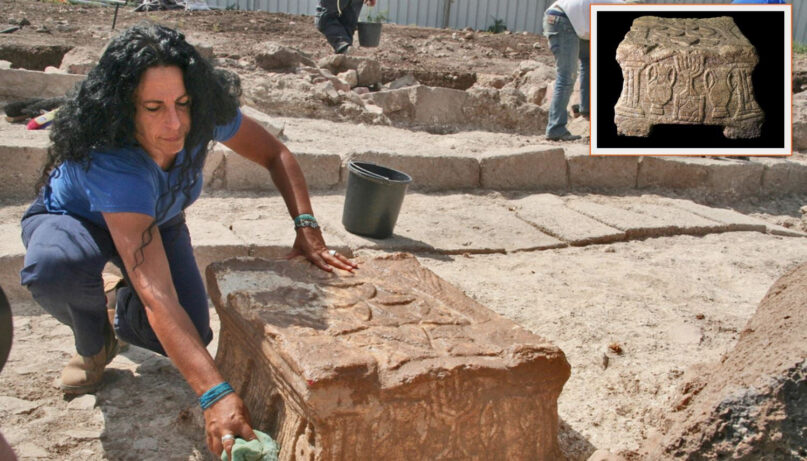

(RNS) — The findings were heralded with bold headlines. Archaeologists excavating near the Israeli town of Migdal, also known as Magdala, had found remnants of a first-century synagogue.

“2nd-Temple-period synagogue found where Gospel’s Mary Magdalene was born,” the Jerusalem Post’s Dec. 12 headline declared. Newsweek, Express UK and the Smithsonian magazine followed up with similar headlines.

The discovery of the ancient synagogue in the town on the western edge of the Sea of Galilee is surely significant and adds tangible evidence of Jewish life in first-century Palestine at the time of Jesus’ ministry.

But two scholars from the U.S. and the U.K. are calling into question the quick assumption that the town is the birthplace of Mary Magdalene, one of Jesus’ earliest followers and the first witness to his resurrection.

In a paper published last month, Elizabeth Schrader, a Ph.D. student at Duke University, and Joan Taylor, a professor at King’s College, London, argue that the assumption Magdala refers to Mary’s place of origin is entirely speculative.

Instead, they say, Magdalene may well be an honorific from the Hebrew and Aramaic roots for “tower” or “magnified.”

Just as the Apostle Peter is given the epithet “rock,” (“You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church”), Mary could well have acquired a title “Magdalene” meaning “tower of faith,” or “Mary the magnified.”

“Although there have been various ways of understanding her name, no author prior to the sixth century identifies her as coming from a place beside the Sea of Galilee,” the authors write in the Journal of Biblical Literature’s December issue. “Several ancient authors actually understood Mary’s nickname to be rooted in her character rather than her provenance.”

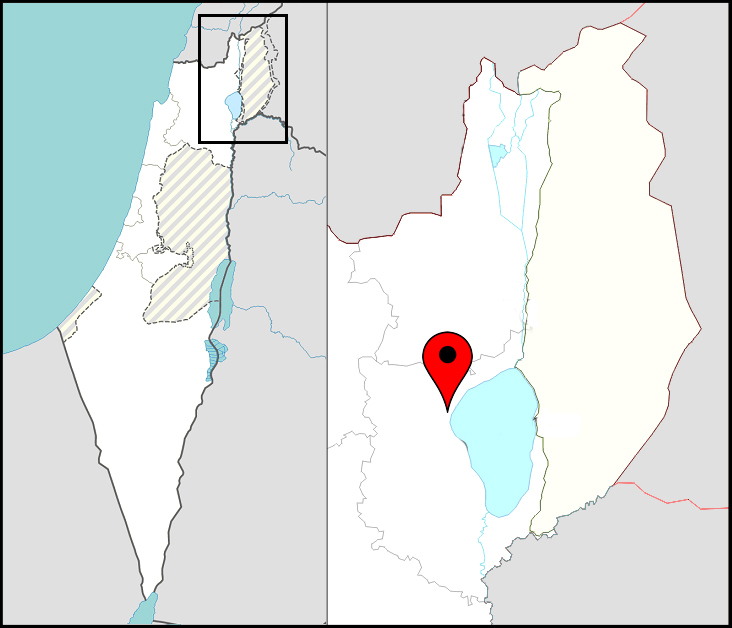

Migdal, red pin, located along the Sea of Galilee in northeast Israel. Maps courtesy of Creative Commons

The paper is part of a reconsideration of Mary Magdalene, long mistaken for a prostitute and marginalized by the early church fathers. Scholars are reexamining the Gospels and early Christian writings in an effort to recover the real Mary from the diminished figure that emerged from the pens of the early church fathers.

Schrader, a former singer-songwriter in the New York pop scene, has been at this task for a while. In a paper published in 2017, she examined the story of the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John. Poring over hundreds of hand-copied early Greek and Latin manuscripts of the Gospel, Schrader found that the name Martha, another New Testament woman, identified as Lazaurus’ sister, had sometimes shown signs of being altered. The scribes scratched out one letter and replaced it with another, thereby changing the original name “Mary” to read “Martha,” in a possible deliberate downplaying of Mary’s role in the story.

RELATED: Scribes tried to blot her out. Now a scholar is trying to recover the real Mary Magdalene.

Mary’s diminishment took place slowly as Christianity grew more patriarchal. Perhaps the biggest blow to her reputation came in the sixth century, when Pope Gregory the Great conflated Mary Magdalene with the “sinful woman” who anointed Jesus’ feet with perfume in Luke 7. That woman is never mentioned by name by the writer of Luke’s Gospel. But for the next 1,500 years Mary Magdalene was often equated to a prostitute, or in modern parlance, a sex worker.

As Schrader and Taylor demonstrate, there was no consensus about Mary or her origins in antiquity. In fact, there were multiple locations named Migdal throughout Judea and Galilee. The fourth-century Christian historian Eusebius thought Magdala was a town in Judea, not Galilee.

St. Jerome, best known for his translation of the Bible into Latin (a version called the Vulgate), said he believed Mary got the name Magdalene because she was a tower of faith — a “tower-ess” as he puts it in a letter from the year 412.

Artist Alexander Ivanov’s 1835 painting “Christ’s Appearance to Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection.” Image courtesy of Creative Commons

Later, during the Byzantine era and especially during the period of the Crusades from the 11th to the 13th centuries, a town near the Sea of Galilee known initially as el-Mejdal became a Christian pilgrimage site known as Magdala. It still is.

“What we’re saying is that it wasn’t a site at the time of Jesus,” said Taylor. “At that time, there was a city called Tarichaea, which is mentioned by Josephus and Pliny. But it was never called Magdala in the Roman period.”

Journalists weren’t the only ones to allege Mary was from Magdala. In a statement announcing the excavation of the synagogue, University of Haifa excavation director Dina Avshalom-Gorni said, “We can imagine Mary Magdalene and her family coming to the synagogue here, along with other residents of Migdal, to participate in religious and communal events.”

For some, rooting Mary in the town of Magdala is important. Archaeologists need funding for their digs. If they can connect their work to a biblical figure or event, private and institutional funding will start pouring in, Taylor said.

Evangelicals in particular, eager to find physical evidence the Bible is historically true, are wedded to the idea that Mary came from the town of Magdala. So are some feminist scholars who want to disassociate Mary Magdalene from the sinful woman in Luke 7.

But situating Mary in Magdala also shuts the door to Mary’s legacy.

“If you say she’s from Magdala it eliminates the possibility that ‘Magdalene’ indicates a title of a more prominent disciple,” said Schrader.

Considering “Magdalene” as an honorific also restores her dignity, added Taylor. “It creates a clean slate for her to be recovered in a fresh way.”

RELATED: Five Christmas sermon blunders that get Judaism (and Jesus) wrong