(RNS) — Artist Safia Latif doesn’t often discuss the thinking behind her lush, loosely brushed oil paintings.

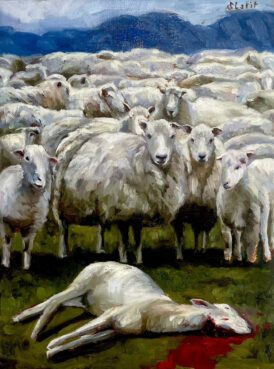

But the day before the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha, celebrated this year in early July, Latif made an exception, sharing the inspiration for her latest piece, titled “The Sacrifice,” with her more than 16,000 followers on Instagram and Twitter.

Eid al-Adha commemorates the story, told in the Quran and the Bible, of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, but Latif characteristically widened its scope.

“The focal point is the slain sheep, representing not only the iconic sacrifice of Abraham submitting his son to God,” Latif explained, “but the many other sacrificial lambs we find in past and recent history, e.g., Christ, Imam Husayn, George Floyd and so on,” referring to the early leader of Islam’s Shiite sect and Floyd, the man murdered by police in Minneapolis in 2020.

“The Sacrifice” by Safia Latif. © Safia Latif

Latif was in the midst of a doctoral program in religion at Boston University when she sold her first painting, itself inspired by a class she’d signed up for at Harvard. The teacher, Ahmed Ragab, a historian, physician and documentary filmmaker (now at Johns Hopkins), gave the class the option of completing a final project with a creative work.

Latif, who had painted for pleasure as a child, rendered the 15th century Moroccan Sufi mystic Imam Muhammad al-Jazuli in a famed moment of ecstatic union with the Divine.

Five years later, Latif has left academia to paint full time and is known for her unique, expressive style, which she calls “Islamicate impressionism.” She spoke with Religion News Service recently about her work, about growing up as the daughter of a Pakistani Muslim immigrant and American Russian Jewish convert to Islam and about collapsing distinctions between secular and sacred art.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Who chose the term Islamicate impressionism for your work?

I came up with it. I feel my artwork is unique in comparison to the prominent forms of Islamic art dominating the visual landscape — calligraphy or hyperdetailed mosque paintings. I’m drawing on Western impressionism to convey Islamic concepts and ideas. I wouldn’t think of (my art) as “Islamic.” To me, that has a sense of being hyperlegalistic or pietistic, and my art is definitely more transgressive.

“Islamicate” was coined by early 20th century Islamic historian Marshall Hodgson and it describes what I’m doing in my artwork perfectly. Hodgson used the term to describe the social and cultural phenomena associated with the Muslim world. I will touch on apocalypticism or Islamic futurism and everyday Muslim devotional life. So I feel like it was a perfect umbrella term to capture what I’m painting.

Are you deliberately being transgressive? Or does the way you communicate the tradition simply strike some people as transgressive?

Maybe it’s a bit of both. To some people it would be seen as an intervention. But also I feel I’m conveying a truth that already exists for so many people.

Artist Safia Latif. Photo courtesy of Latif

My father is traditionally devout and very pious, so, I’ll test it out on him. The first thing he said (about “The Sacrifice”) was, “Well, you know, we don’t sacrifice the sheep in front of other sheep — that goes against Islamic slaughtering laws.” It was so funny. I had to remind him, this is art. I’m not trying to say something about Islamic law. You kind of have to think beyond that.

There’s an animal rights impulse in it. As a little girl I visited Pakistan during Eid al-Adha. It’s literally a bloodbath. You walk down the street, there is blood running everywhere, animals being sacrificed in the street. You can smell that raw meat, blood in the air. I remember as a child, I just refused to eat all day. I didn’t want to touch any meat.

I’m not unique in this. There are other Muslims who feel the same thing. Do we need to kill as many animals as we’re killing or sacrifice as many? So that was one message I was sending out. And then beyond that, reflecting on this idea of sacrifice.

RELATED: In ‘Ms. Marvel’, Muslim fans see a reflection of their lives

Is your art ever considered ‘too religious’ for the professional art world?

Oh, definitely. I’ve thought about that a lot because I’d like to enter the gallery scene. Other artists I follow, Christian artists, are doing similar things. Gary Bunt’s work is amazing. Any artist who dabbles in religion or religious themes in their artwork is going to run into a hurdle because most of what you see in the gallery world is “secular” art.

But Sargent, Rembrandt, even Picasso had religious paintings. Andy Warhol had religious paintings. But if you’re a religious artist, that’s somehow different from being this “secular artist.” I think there’s a way to marry the sacred and profane.

How have your parents’ backgrounds shaped your understanding of your faith?

I grew up very Muslim, going to the mosque every weekend. My community was predominantly South Asian and I was seen as the white girl. I don’t see myself as a white girl, or a purely South Asian girl either. But to them I was white. I had my foot in that world, but one foot was outside of it. My mom, a Jewish convert to Islam, had my older sister (in her first marriage). That older half sister is Christian. I’ll join her for Christmas. She was just here for Eid. She celebrated with my in-laws and we exchanged Eid gifts.

When you enter academia, you realize that so much of what we believe about our religious traditions is socially constructed. (That’s) not to say that what we believe isn’t true, but I think it lends itself to this idea of human solidarity — like, we’re all humans at the end of the day, we’re all searching for the truth.

RELATED: Black Muslim life honored in new online portrait exhibit

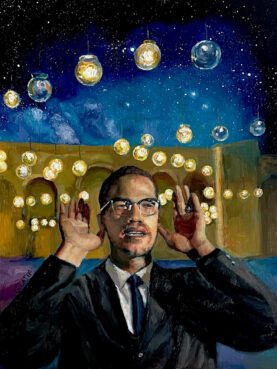

Your Space series features Black Muslim icons Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. Early American Muslims appear in your Prayer on Plantation series. How did these two projects come about?

“Space Mosque” by Safia Latif. © Safia Latif

One of my academic advisers in my master’s program (in Middle Eastern studies at the University of Texas at Austin) was the scholar Denise Spellberg, who wrote “Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an.” Her course on American Islam started me thinking about the first American Muslims, who were African slaves. That’s what started my Prayer on Plantation series.

When I think of a Muslim icon that shaped my teenage years, that would be Malcolm X. Muhammad Ali, he was winning fights and gave Muslims all over the world so much hope, especially in a time where, you know, they were suffering socio-politically.

A lot of times when I’m painting I’ll listen to documentaries, a lot of space documentaries about NASA and things like that. I guess that spilled into my artwork. And it just turned out that Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, they were the perfect subjects. I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of painting them.

How do you hope your art is appreciated?

I would hope that I am conveying something universal — this sense of beauty, just like any good piece of artwork, but then also this truth about human beings and about ourselves and our history. And I wouldn’t like for it to just be this art that only belongs to the Islamic world. I would hope that it would be appreciated by others, non-Muslims as well.

For Muslims, I hope it broadens their understanding of Islam. Islam cannot just be reduced to law, which so much of it is today. If you look beyond that you can have a more open view of Islam and you can be more accepting of different expressions of piety and religiosity and different ways of being Muslim and inhabiting the world.

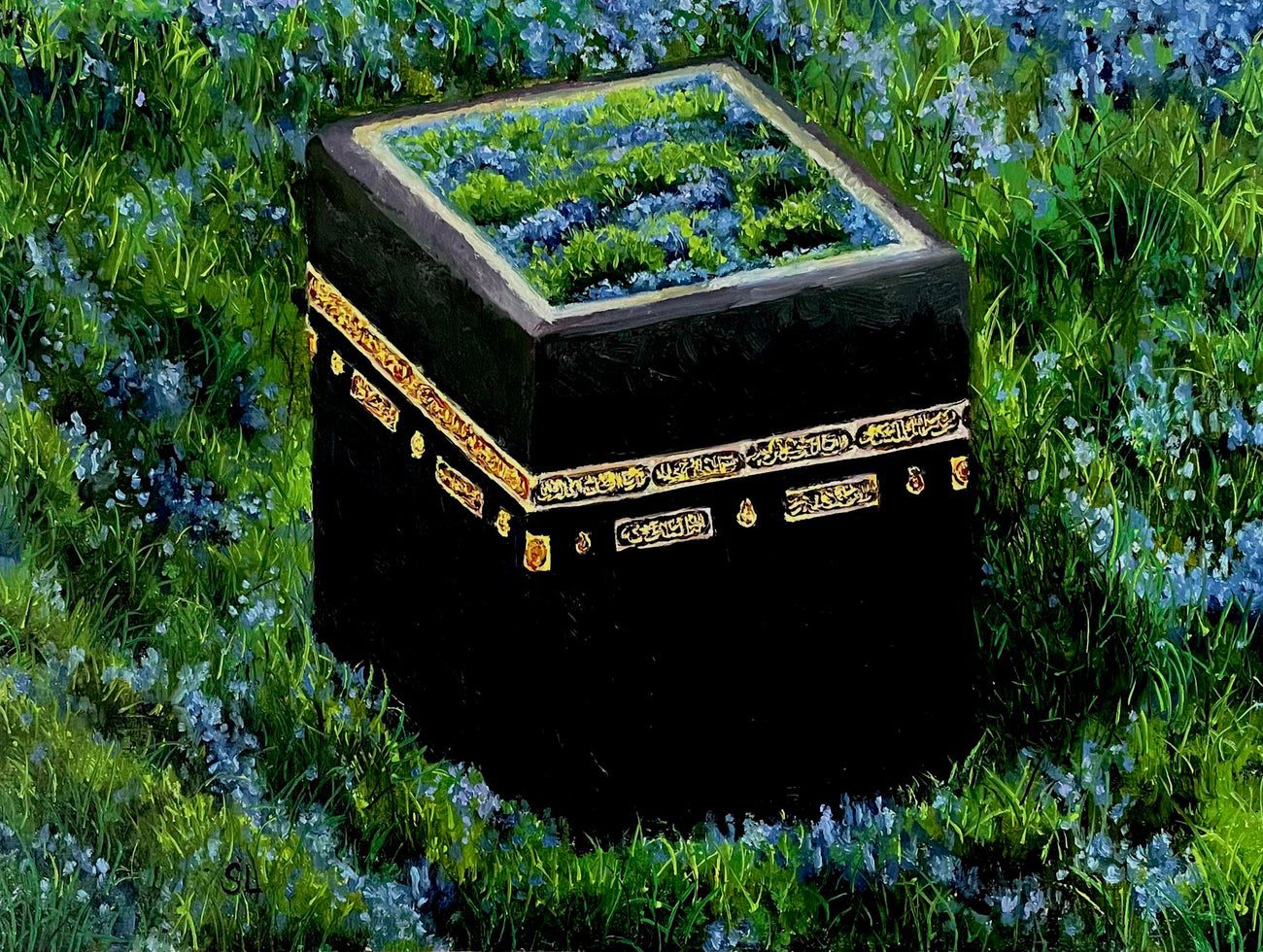

“Epilogue II” by Safia Latif. © Safia Latif