Indigenous women lead the Tucson 2019 Women’s March in Tucson, Arizona. Photo by Dulcey Lima/Unsplash/Creative Commons

Trigger warning: Content about abuse, the death of a child and brutal American policies toward Native Americans.

(RNS) — The destruction of Native American lives, cultures, languages and traditions is a scar on American history that disrupts simplistic narratives of American democratic ideals and exceptionalism. The numbers alone are shocking: The Native American population, about 10 million when European colonialists reached the United States, plummeted due to disease, murderous policies and forced assimilation to less than 300,000 by 1900.

Until 1960, the Native American population recovered only slowly, as high birth rates were undercut by high rates of mortality, the latter a symptom of continued oppression. Since then, however, the Native American population has grown rapidly, especially over the past decade.

As they increase in number, many Native Americans and those of mixed Native and European and African ancestry are reclaiming their heritage, notably spiritual rites, rituals and traditions. These practices, filled with linguistic, social, gustatory and historical significance, have been pursued in part as a search for self and story.

Yolonda Blue Horse’s search began after she experienced a devastating loss and nearly lost the right to raise her children.

RELATED: An awakening is coming to American religion. You won’t hear about it from the pulpit.

Blue Horse and her husband had moved to the Dallas area in 2000 after her then-husband was serving in the United States military and was transferred to Fort Hood. (Blue Horse had also served in the military but had been discharged by this time.) Blue Horse had arranged for a neighbor to watch one of her three children so that she could go to work during the day.

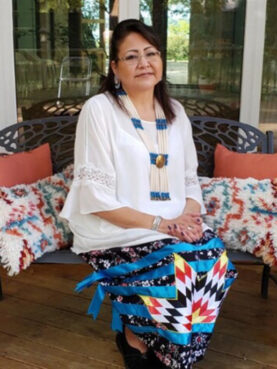

Yolonda Blue Horse. Courtesy photo

A few weeks later, she got a call from a hospital explaining that her daughter had died. Rather than investigating her neighbor, however, law enforcement and Child Protective Services investigated Blue Horse and her husband. CPS removed their other two children from their care for more than a year, raising the specter that, in addition to suffering the loss of one child, they would lose all three.

Only after Blue Horse initiated a wrongful death lawsuit against the neighbor did the government agencies begin to take seriously the possibility that Blue Horse and her family were not at fault. It took years, but law enforcement and prosecutors gathered enough evidence to charge and convict the neighbor with murder.

By that time, Blue Horse’s marriage began to fall apart. Decades later, her children continue to struggle emotionally. The tragedy remains alive.

But as she grieved, Blue Horse recognized that prejudice was behind the grossly unfair treatment she had endured. The realization led her to reconnect with her Lakota Sioux heritage, learning the culture she had mostly ignored until that point. “It’s been a lot of searching over time,” she said, “a lot of being able to experience our ceremonies and learning … (about) where I come from and who my ancestors are.”

Blue Horse said her own experience taught her that Native Americans, despite their shared trauma and harrowing history, need to stand up and be counted. “We are dealing with the painful situation the best way we can. But for myself, it was learning how to have a voice, learning … and speaking up for different things.”

In time she became a lay leader, a figure who could speak to audiences about her tradition and represent the Lakota People and Native Americans in the Dallas community.

Today Blue Horse advocates for the needs of Native American groups, teaching outsiders about her tribe’s customs and traditions. She has served as director of the Indigenous Cultures Program at the Memnosyne Institute, a humanitarian NGO; has galvanized protests against the Dakota Access pipeline; and works for the countless Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

Yolonda Blue Horse, left, and Diana Parton protest with others before an NFL football game between the Dallas Cowboys and Washington Redskins, Sunday, October 13, 2013, in Arlington, Texas. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

She also encourages American communities to engage with the history of the land they occupy, which often was taken forcibly from Native Americans. Her work has been instrumental in convincing schools and sports teams to change the name of mascots that offend Native Americans by instilling an appreciation of Native American rituals and traditions.

Much of Native American spirituality is grounded in the land — and often in a tribe’s traditional environment. “We utilize things in nature to be part of, for lack of better words, our church building,” she said.

Living in Dallas, far from her own Rosebud Sioux Tribe, which has a reservation in South Dakota and is part of the greater Lakota Nation, she delights in both the commonalities and differences among Native peoples.

Noting how movies and television tend to blend the culture into one, Blue Horse emphasizes the uniqueness of each tribe: “We have different languages, we have different beliefs, we have different entities, different words to call the Creator.”

But the tribes in Texas share spiritual practices with the Lakota. “We always know to pray even when we sit down and eat together. We burn sage to help bless us to help clear the air, and then we have sweetgrass that we use.” Some rituals have also migrated from one group to another, including the sweat lodges she knew growing up. “For some of the tribes it’s either part of their culture or they’ve adopted it, so there are some different sweat lodges I have been through down here.”

Yolonda Blue Horse in the PBS “American Portrait” series. Video screen grab

She has invested in this shared culture by co-founding the Society of Native Nations, in part to make Texans aware that there are Indigenous Americans among them, even if the federally recognized tribes are not native to Texas.

Blue Horse does not hold herself up as an exemplar, so much as an example of a rising cohort of leaders within the Native American tribes and communities with which she is familiar.

“There are so many that are up and coming, you know, where we’re boosting each other to get out and speak, that you can talk, you can use your voice.”

RELATED: An immigrant Muslim finds his model of empowerment in Black American Islam

For Blue Horse, leadership, especially her public speaking, has taken on the dimensions of spiritual practice. “I always try to remember any time I go out and do a speaking event, this is not my words, these are Creator’s. … Let your words come through me. … Let me know, let what you want me to say come out of … my mouth.

“You know, before all of what happened to me in 2000, I would have never dreamed of, you know, being on a PBS documentary (in January of last year). You got to get it done, you got to talk, because if you don’t talk and if you don’t tell people about what’s going on with Native people, how will anybody ever know?”

AMERICAN AWAKENINGS: Read all the interviews in this series