(RNS) — In the late 1800s, a group of German-speaking Mennonites left southern Russia and journeyed into Central Asia following the end-time prophecies of a charismatic preacher. But while the story of these Mennonites’ perilous journey into Uzbekistan is riveting, for Sofia Samatar, the real story begins after the end of the world failed to arrive.

In a desert surrounded by Muslim strangers, the Mennonites built a village and chose to say.

“I was very interested in the story of these people who apparently lived together amicably with their Muslim neighbors for quite a long period of time,” Samatar told Religion News Service in a recent phone interview.

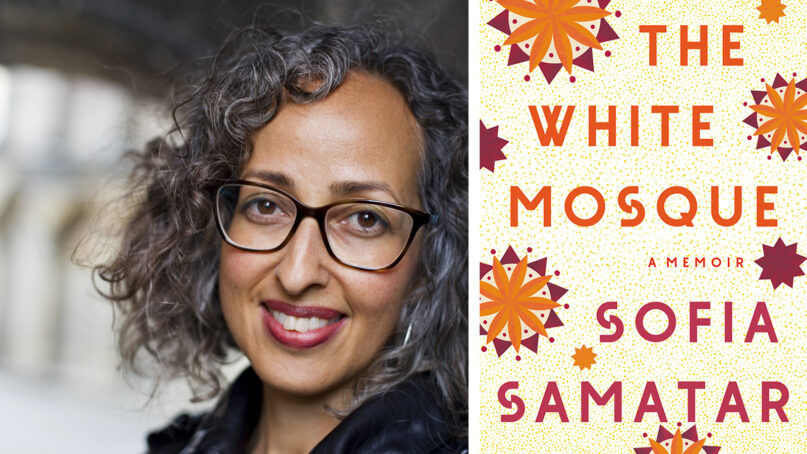

A Mennonite of color with Mennonites on one side of the family and Somali Muslims on the other, Samatar, a novelist and professor of Arabic and African literature at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, was fascinated by this early example of Muslim-Mennonite interaction. Drawing from seven years of research, writing and a journey to and from Uzbekistan, Samatar’s “The White Mosque” is an intricate, textured memoir that intertwines the author’s personal history with the stories of the German Mennonites of Ak Metchet, the village they built.

Though not a descendant of these Mennonites, Samatar says she has inherited the same stories that shaped this community birthed by apocalyptic predictions — the stories of the Bible and of the Martyrs Mirror, the Anabaptist compendium of martyrs’ tales.

“Sharing a reservoir of images, sharing the same references to stories and histories, singing the same hymns, those things to me are much richer in how they shape a person,” Samatar told RNS. “Those forms of belonging that do not have to do with DNA are part of what I was interested in exploring. In that way, I share an enormous amount with these Mennonites.”

Samatar spoke to RNS about growing up as a Mennonite of color, the lessons we can glean from the Mennonites of Ak Metchet and the complexity and expansiveness that accompanies Mennonite identity. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why call the book “The White Mosque”?

That is the direct translation of Ak Metchet, the name of the Mennonite village. One story about how it got its name says the Mennonites had a church in the middle of the village square, a whitewashed building. The story I heard was that, to the local Muslim population, this building was known as the white mosque. The idea is that it was a church that was seen as a mosque.

You call yourself a secular Mennonite. What does that mean?

The term Mennonite is both a denominational and an ethnic term. So we do speak of ethnic Mennonites, similar to the way people might talk about being Jewish. You could be a practicing Jew, or a nonpracticing, ethnic Jew. If you spend any time around Mennonites, you’ll recognize that everybody has the same name, and there’s almost a family or clanlike feel to a lot of Mennonite circles in the U.S. But this is not something that there is 100% agreement on among Mennonites. Mennonites in the U.S. are quicker to see being Mennonite as a matter of faith. In Canada, however, Mennonite is seen as an ethnic minority.

What happened to the Mennonites of Ak Metchet after the end of the world didn’t come?

What was interesting to me was to look at this group of people as a model for what you do after everything falls through. They were building extra buildings for refugees they expected would flock to them in the end times. They were not planning for the future. They didn’t seek out farmland, they were happy to do carpentry jobs and make socks and butter to sell at the market. But after everything fell through, they stayed there and reinvented themselves as a community. It was very interesting to me that they were able to overcome this massive, shocking disappointment and continue. And I did not find a case of them being harassed or made to feel unwelcome in any way, until 1935, when they were deported by the new Bolshevik government. But that had nothing to do with Islam. The new regime was against all religions.

What is the missionary effect, and how have you witnessed it in your own life?

The missionary effect is my term for a particular strain of the dominant culture of Mennonites in North America that I have grown up with. We love to be of service, which seems very good. But embedded in that idea of serving others is the idea of having something to offer, having something others do not have, so in some way being superior to others. That’s something I certainly grew up with in my household. My mother met my father working for a Mennonite missionary organization in Somalia as an English teacher. I grew up hearing how lucky my dad was that Mennonites found him and enabled him to have a good life. That is insulting, and racist, to be frank. So that ethos or cultural aura is something that is very familiar to me. And something I point out in the book is, nobody said how lucky my mother was to work in Somalia, though it was her experience there that enabled her to have a career teaching English as a second language.

What is the Mennonite wall, and how does the missionary effect contribute to it?

In 2016, about six months before my trip to Uzbekistan to do research for this book, I went back to my alma mater, Goshen College in Goshen, Indiana, for the first time in 20 years. There was a public forum on the racial climate at Goshen College. It was quite saddening that the kind of conversations students of color were having were the same as what I and my friends had experienced as students of color 20 years before. They were having the same conversations about being shut out, being seen as an extra or interloper, someone who didn’t fully count. The students of color talked about what they called the Mennonite wall, this exclusive white Mennonite group identity they couldn’t get through.

I see a connection between what those students call the Mennonite wall and this missionary effect. Those students actually come from where most Mennonites are. Our fastest growing church is in Ethiopia. Only a small percentage of Mennonites globally live in North America, and that includes Black and Latino Mennonite communities. It’s actually a tiny number of the Mennonites globally who are in charge of the story of who Mennonites are. Part of having control of that story is being the ones who have something to offer, the story tellers and creators. Whereas most of the world’s Mennonites, those outside that group, are framed as people who are receiving from Mennonites, not creating Mennonite stories.

Can you tell us about one of the individuals whose life unexpectedly intersects with the community of Ak Metchet?

Irene Worth was the granddaughter of one of the Ak Metchet Mennonites. Her grandfather died in Central Asia. Her grandmother, with her father, who was then a little boy, moved to Nebraska. She was then born there as Harriet Elizabeth Abrams. When she grew up, she took the stage name Irene Worth and became a well-known actor on stage and screen.

She worked primarily in England. She did Shakespeare, played Desdemona. People called her the intellectuals’ actress because she was in plays by Samuel Beckett and T.S. Eliot, these influential avant-garde writers. She was phenomenally gifted, and almost silent about her background. There are no interviews in which she talked about her family ever being Mennonites. We don’t know how much she knew about the story.

Following these threads was a deliberate strategy of openness to the many different ways people’s stories are intertwined. It’s a way of working against a rigid narrative, where we always interact with people in the same way. The world is so much wider than one narrow interpretation of Mennonite identity.

RELATED: Mennonite Church USA passes resolution committing to LGBTQ inclusion

Did your experience of writing this memoir have any influence on your spiritual beliefs or practices?

Not an effect on beliefs or practices, but it certainly made clearer to me the kind of fellow feeling that can exist among people of different faiths. That is something I and the rest of my tour group saw when we went to Uzbekistan. The people there, they remember the Mennonites. There is a Mennonite museum in the city of Kiva, a project that people there have been working on for years. They have photographs, sewing machines, lamps that belonged to the Mennonites that they have preserved. They remember these people as good neighbors, and as folks who were torn out of the home they had made because of their beliefs. There is a sense of connection, a sense of sympathy there between these groups, recognizing this was also a community of faith, and we support communities of faith no matter who they are.

What do you think the strength of the Mennonite church is today?

We can’t seem to figure out if we are a faith group or an ethnic group. We can’t come to a consensus. And it feels like a problem, these different definitions of what Mennonite means. But I actually do think that to be forced to reckon with these different forms of belonging is a strength. You have to grapple with the fact that there are different ways people are related — ethnicity, beliefs, stories, cultural practices — and all these different kinds of relationship can overlap. That’s what happens among Mennonites. You have overlapping ways of belonging, and while we have a lot of work to do to figure it out, I ultimately think it’s a strength.

RELATED: Prominent mosque in Germany sounds 1st public call to prayer