(RNS) — Yogis fortunate enough to practice under the late R. Sharath Jois, who died this past Monday (Nov. 11) often characterize his demeanor as equal parts firm and gentle. Some were intimidated by his penetrating gaze and unyielding approach to yoga practice, but many fondly remember his sly, under-the-breath witticisms, most deployed as students held a challenging yoga position for longer than seemed necessary.

He will also be remembered for his warmth. “No one could see him and not have the experience of him smiling at you,” said John Campbell, a Buddhism scholar who is one of the few yoga teachers certified by Jois. “That was a natural state of his face: tremendous beaming, warmth, approachability and kindness. Even the people who have not met him, whatever yoga has been shared with you, he has been a part of that.”

Heir since 2007 to Ashtanga yoga — the rigid, disciplined and strenuous exercise often recognized for headstands, backbends and something called the “pretzel” — developed by his grandfather, Pattabhi Jois, in the late 1940s, Jois began teaching as a teen in the 1990s beside his mother, Saraswathi, at the family’s shala, or school, in Mysore, India.

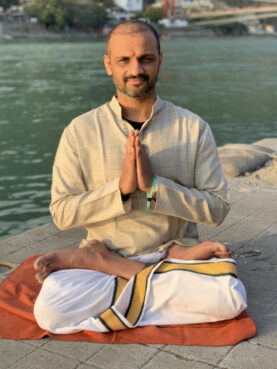

R. Sharath Jois was a primary figure in the Ashtanga yoga community. (Photo via Instagram/@sharathjoisr)

Last week, an otherwise healthy 53-year-old Jois died suddenly of a heart attack while hiking with students in the Blue Ridge Mountains after teaching an international group of yogis at the University of Virginia. The worldwide yoga community is still in shock.

“For our generation, yoga practice was like a backdrop, figuratively speaking, for this journey of growth, of self-reflection, of connection with each other, and hopefully even a connection with God,” said Dan Loeb, a hedge-fund manager and former yogi who met his wife through the Ashtanga community. “Sharath was central to that as someone who was part of that lineage. What a privilege to live in that time and space, and to have that chance.”

The Ashtanga community is now left with a reckoning — what happens after a lineage is disrupted so unexpectedly?

On Thursday (Nov. 14), the Broome Street Ganesha Temple, a spiritual home in New York for the Jois family established in 2001, former disciples and admirers gathered for a memorial service. Yogis exchanged stories of their time with the mild-mannered Jois and prayed and chanted in unison from the second chapter of the Hindu Scripture Bhagavad Gita — verses that speak about a soul’s transition to the next phase of life.

Many well-known instructors in the tight-knit Ashtanga community had flown in to pay their respects, including Richard Freeman and Mary Taylor, a duo who met a young Jois when he was still “less than interested in yoga,” and more keen on his passion, wildlife photography.

“In the very beginning, there were maximum 12 people in the room, and sometimes just two,” said Taylor, gesturing to the crowded space at the temple and those gathered on Zoom. “And you know, look what has happened, and look at the gift that he and his family had given to us.”

Pattabhi Jois, also called Guruji, studied yoga, Sanskrit and Vedic philosophy under T. Krishnamacharya, widely considered the “father of modern yoga.” Jois refined and formalized some of his teachings into the modern Ashtanga practice, which appealed to those swept up in both the fitness and spirituality booms of the 1980s and ’90s. Celebrities such as Madonna and Sting helped to popularize the athletic yoga form.

His grandson, Sharath, said Broome Street’s founder and Ashtanga yogi Eddie Stern was an “innocent” and “enthusiastic” teenager when Stern came to train under Guruji. Their close friendship, spanning more than 30 years in both India and New York, hit a difficult transition period after Guruji passed. New York, said Stern, was always appealing to Jois, who spent time walking the streets and peeking into his favorite outdoor equipment stores, REI and Fjalraven.

Recent posts on Sharath Jois’ Instagram, where he had more than 230,000 followers. (Screen grab)

The news of Jois’ sudden passing, said Stern, who had just met with him, his wife and two children in August, was hard to believe. “There’s almost no coping mechanism for that,” he said. “It’s completely unfathomable. I think everyone is still coming to terms with it. It’s gonna take some time for it to settle in.”

Stern and his wife, a fellow practitioner, traveled to Virginia almost immediately to sit and meditate in his final resting place, a “serene, almost mystical setting” along a lengthy trail. Students who went on the last hike with Jois told reporters he took a rest on a bench during a steep climb and collapsed soon after.

“He was a very kind and very warm-hearted person,” said Stern. “He gave a lot of himself. He was very present with his students, and he had a tremendous memory as well for people, their stories, their family, who they were, what they were struggling with. So I think one of the things that many of us learned was to be very, very present with your students as you’re teaching, but also present with remembering and recognizing who they are as people.

“It makes it so we continue to humanize this entire thing of yoga and not make it just bodies doing postures and breathing, but the people who are doing it.”

For the greater yoga community, Ashtanga yoga still has a reputation as intimidating, formal and “almost culty.” Its lack of muscle-sparing modifications and serious atmosphere make it less approachable than Hatha, Vinyasa or Kundalini, some say. What’s more, said yoga teacher Kat Capossela, Ashtanga yogis are prone to injury due to the lack of playfulness and grace she says are natural to her Vinyasa practice.

Kat Capossela, left, poses with Sharath Jois recently in Harlem. (Photo courtesy Capossela)

Capossela has heard of Jois banishing students unable to perform to the back of the class and initially felt fearful of Jois’ no-nonsense attitude when she attended a class with him in New York days before he died. But she said no other form of yoga had “made her body feel better.”

“It’s a stark reminder that no one practice is going to save you from life and the realities of it,” she said of Jois’ death. “No matter what dogma or religion or practice you adhere yourself to, at the end of the day we are all human and at the whims of something larger than us.”

“I think it’s going to be a real reckoning for the international Ashtanga community, because they relied so heavily on the lineage,” she added. Without a Jois to lead Ashtanga, she fears it will slip into a commercialized version she has seen Vinyasa and Hatha become in the West. “I’m almost hopeful that with this disruption, the community can take a hard look at itself and think about how it can become more accessible to less dogmatic populations,” she said.

In recent years, said Stern, Jois was indeed concerned about increasing accessibility and in his last teaching sessions in Virginia had introduced an “Active Series” that took a lighter approach, even stripping it of its Sanskrit language barrier.

“He was trying to break that entryway down by simplifying a lot of the postures, leaving some of the complicated things out, making it less demanding in certain ways,” he said. “In these very last years, a lot of the message was to soften, to simplify, to not overdo it. I think that’s a really beautiful parting gift as a teacher, to leave something behind which is going to be even more useful than it was when they were here.”

A portrait of Sharath Jois is adorned with flowers before a memorial service in his honor at the Broome Street Ganesha Temple, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in New York City. (RNS photo/Richa Karmarkar)

Stern said that in Hinduism, gurus are likened to trees that provide the shade of knowledge while spreading seeds far and wide to their disciples.

“Now it’s up to all of us to continue to let those seeds that we’ve received sprout,” he told his fellow yogis. “We have to attend to them and care for them and give them love and water them. And they will grow and flower, and they will turn into the next thing.”