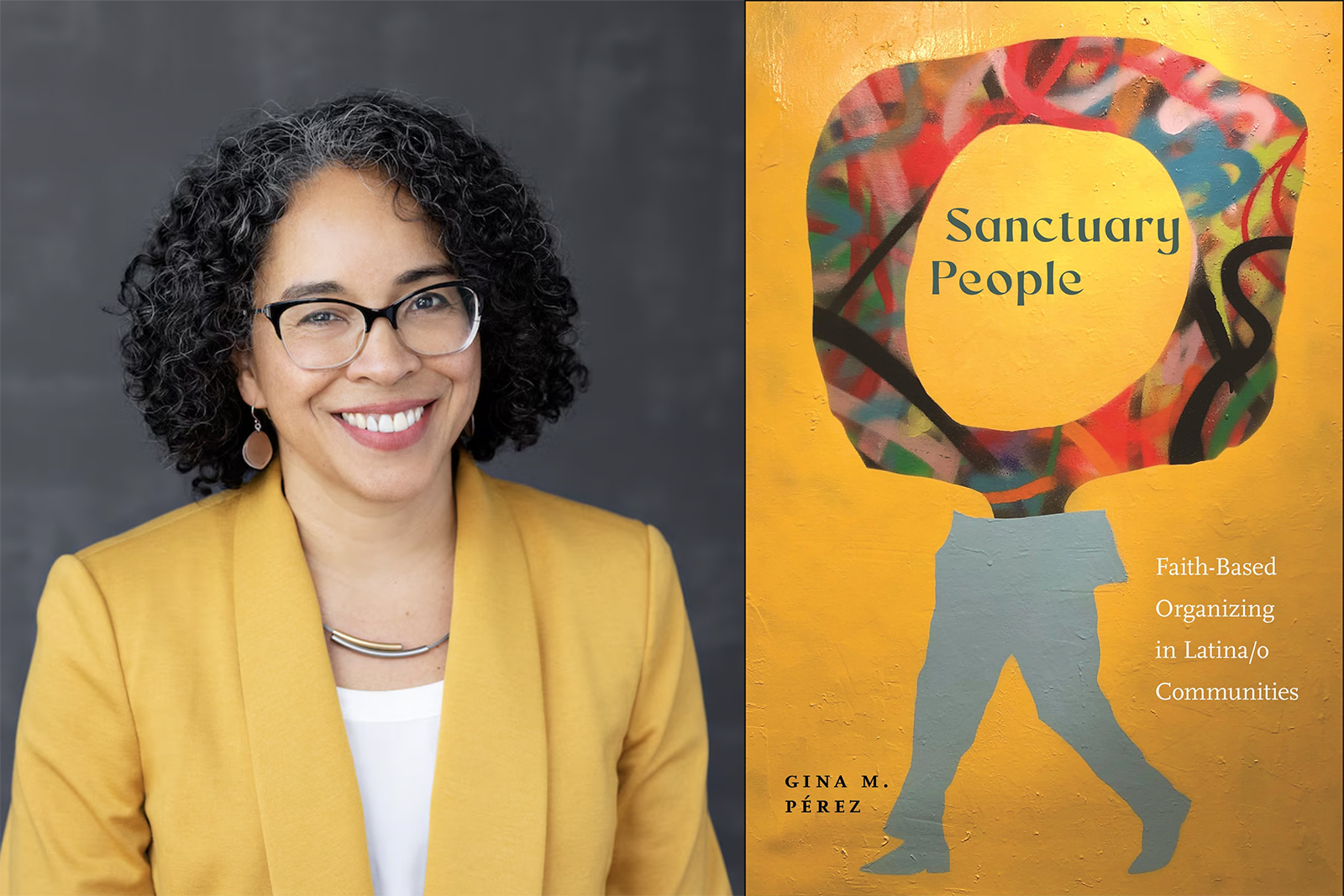

(RNS) — Days before the recent U.S. election, Gina Pérez, author of the new book, “Sanctuary People: Faith-Based Organizing in Latina/o Communities,” said many people in the sanctuary movement, which shelters migrants and refugees, “can’t even bring themselves to think about” the implications of now-President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign promises of mass deportations.

But Pérez, a cultural anthropologist and professor of comparative American studies at Oberlin College, said the community showed resilience in the first Trump term — four years she had spent participating in and observing faith-based communities in Ohio, which had some of the highest numbers of immigrants seeking sanctuary in churches to avoid deportation.

“From its inception, sanctuary’s appeals to divine power and the authority of God have been a powerful way to challenge the secular and punitive power of the state,” Pérez, a Roman Catholic, writes. In conversations before the election, Pérez made clear that many migrants faced grim prospects with Kamala Harris.

In “Sanctuary People,” Pérez takes a hopeful look at a broader understanding of the sanctuary movement that provides not only shelter to those at risk of deportation, but hospitality to Puerto Ricans in the wake of Hurricane Maria and solidarity with those impacted by police violence.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

How do you define sanctuary?

In the 1980s, faith-based organizing really focused on Central American — namely Salvadoran and Guatemalan — migrants and people seeking refuge in the United States or Canada. They were leaving the U.S.-fueled violence in Central America and coming through U.S. faith communities. That was my first introduction to sanctuary, when I was a student at the University of Notre Dame, thinking about churches as sacred spaces offering sanctuary.

The New Sanctuary Movement begins around 2007, under the Obama administration, when people who had lived undocumented for a very long time were evading and trying to challenge deportation to remain with their families. There was a famous case in Chicago of a woman, Elvira Arellano, who took sanctuary in a church for more than a year.

Following Trump’s (first) election, I became interested in how, suddenly, people were talking about sanctuary in a variety of ways. Trump immediately wanted to target sanctuary cities, but a bunch of faith communities declared themselves sanctuary churches. At Oberlin, as at more than 200 colleges and universities, students, faculty, staff and administrators organized to get their campuses designated as sanctuary campuses. I became interested in people who were using the term sanctuary more broadly.

This idea of accompaniment, of a preferential option for the poor, of walking with people through struggles and through the ways that they have to face different kinds of injustice, was something that very much informed both my faith, but also the kind of politics that I was trying to be involved with. I see accompaniment as being one sanctuary practice.

You write about the community’s devastation in 2018 after Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested 114 workers at an Ohio garden center and compare this to the response to Puerto Rican arrivals after Hurricane Maria. How are those two responses intertwined?

After the raid, people in Ohio were starting to take sanctuary in houses of worship, and there was debate within the Diocese of Cleveland about whether its churches would (offer) sanctuary, as Presbyterians and Mennonites and Lutherans (were). One of the things that came out of those discussions was a recognition that sanctuary had become this politicized word.

One of the organizations working with churches made this explicit connection — that everyone who was here for Puerto Rican migrants when they arrived in 2017 after Maria were going to be here in the same way. The same networks of support would help these families devastated by this ICE raid. They were using that language of sanctuary to talk about Puerto Rican migrants needing a place to feel safe and welcome and using that same language to talk about people being split apart from their families.

People were (also) organizing and using the language of safety and sanctuary to talk about providing support for families, for women of color and Black women who lose their children to police violence.

Celestino Rivera, the late police chief of the city of Lorain, Ohio, is a key figure in the book. How did he reconcile the tension between his official role and his support for sanctuary?

Celestino was called to a meeting by a local priest, Father Bill Thaden. Some of Lorain’s immigrant rights association wanted to meet with him. Celestino asked, “What can I do, Father? How do I prepare?” Thaden said, “No, they want you to listen.” They brought him in to hear what the policing practices actually looked like on the ground. It opened his eyes to the ways that moving car violations, for example, were setting in motion immigrant detention of people and separating of families.

He was able to develop policies that wouldn’t necessarily be formally considered sanctuary policies, but that emphasized the job was to enforce city laws, not necessarily federal immigration laws.

Did organizers ever talk about rising religious disaffiliation and what that means for the future of sanctuary?

There is some concern, both in academic circles as well as some of the organizing circles, about the secularization of sanctuary. I don’t necessarily think that means that that’s cause for concern. There are plenty of people who still see progressive, social justice faith-based action as important. People are willing to work with faith communities, even if they don’t share those religious theological epistemological premises.

I work at a secular institution with students who weren’t raised in any faith tradition or have a kind of skepticism around them or have bad feelings because of bad experiences. And the public discourse around religion has been so consumed by the religious right and white Christian nationalism that sometimes the history of these progressive faith-based organizing and social movements gets lost.

But one of my jobs as a professor is to expose students to (faith traditions’ social justice) histories, (and) that makes it possible for people to reorient themselves to faith communities.

What’s your source of hope?

There’s a lot of sources of hope for me. Part of it is working with young people who want to make the world a better place, who see a lot of injustice around them, who don’t want to embrace the status quo, who really believe we can create a different world and create a different order.

I was inspired by recognizing that people have been doing this work for decades, and that through community and through relationship with each other and with God, that has sustained them, and that’s what grounds the work that they do even in bleak times.

How are faith-based communities preparing now for Trump’s second term?

What seems to be emerging is a renewed focus and attention to the power of churches, sacred spaces and sanctuary specifically as a way to support immigrants as they face renewed threats of deportation.

This includes attention to ecumenical organizing across differences of class, education, language, citizenship and race or ethnicity. Lessons learned from 2016 to 2020 are informing strategies among faith-based groups, including meeting with immigrant communities to share information about legal resources, hear concerns, affirming sanctuary city ordinances and policies, conversations with local elected leaders and law enforcement.

So while the days following this election definitely felt different than before, a couple of weeks in it is clear that people are centering faith-based organizing in ways that show continuities from the past. Part of what my book documents is that sanctuary people continually draw on histories of resistance and faith to face and respond to the present.