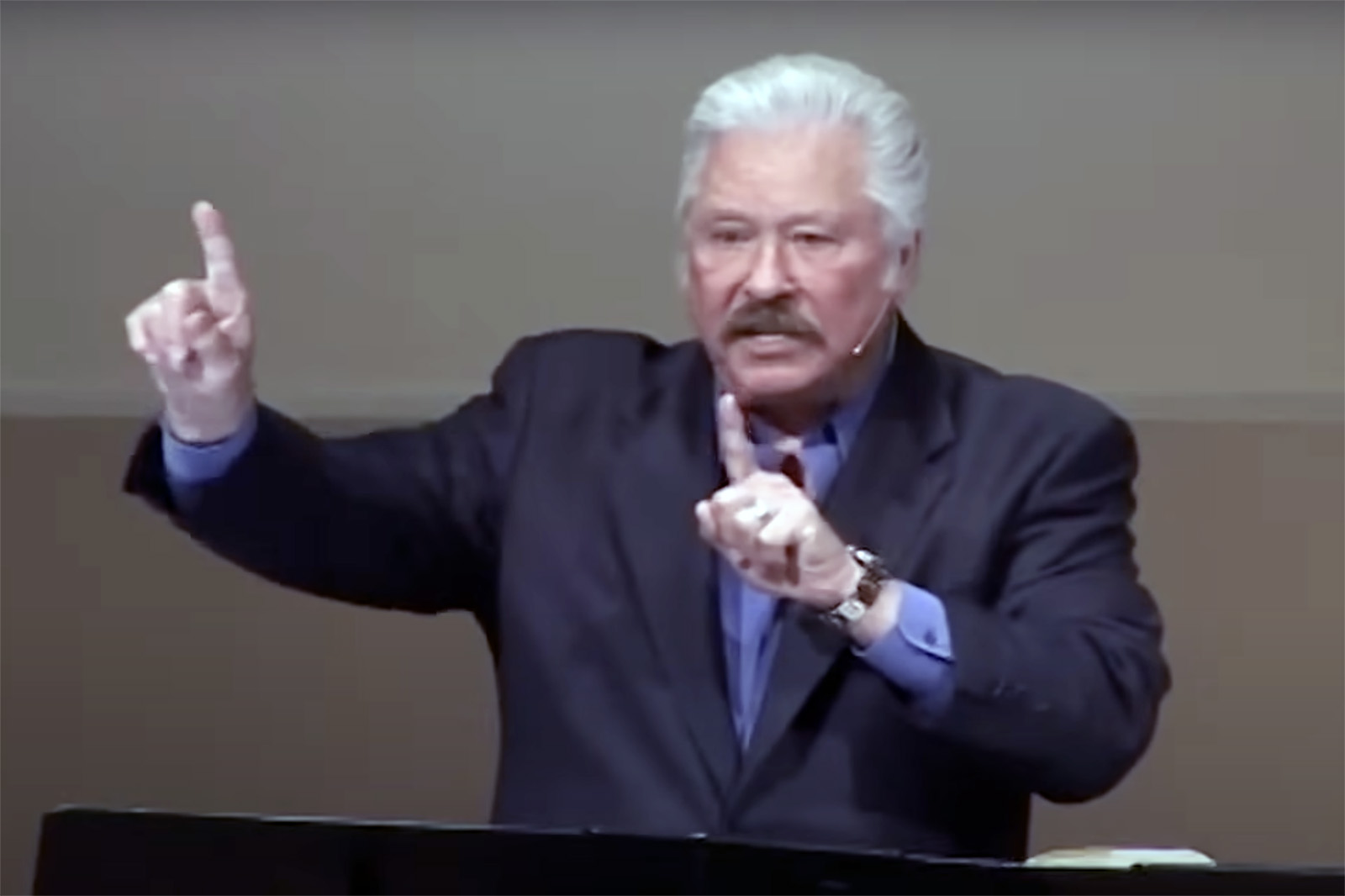

(RNS) — In 2012, I tried to track down Hal Lindsey. I reached out to his ministry, looking for his contact information. I needed his permission to reprint excerpts from his apocalyptic book “The Late Great Planet Earth” in a textbook I was putting together on the rise of the religious right. No one seemed to know how to get in touch with Lindsey, the man whose name was on the ministry masthead and its singular star. Apparently he did not actually work on the organization’s grounds.

Lindsey, who passed away last week, was living in an undisclosed location unknown to even his employees and was possibly somewhere off the grid. I realized at that point that perhaps Lindsey actually believed the conspiracies he had long peddled. But I was never sure.

In this era of alternative truth, deep-state cabals and global puppet masters, it is more important than ever that we understand how and why so many Americans believe that spiritual forces secretly drive international events and today’s news. Hal Lindsey helped lead us into this era, which makes him one of the most important evangelicals and perhaps one of the most important Americans of the 20th century.

Born in 1929, Lindsey converted to evangelical Christianity in the 1950s while working as a Mississippi River tugboat captain. He went to Dallas Theological Seminary in the early 1960s, where he learned the nuances of premillennial eschatology (a particular branch of end times theology). Theologians had resurrected and revived premillennialism in the late 19th century, and it shaped the fundamentalist movement as well as its postwar manifestation known as “evangelicalism.”

Lindsey and his fellow students determined that the world was careening rapidly toward a series of cataclysmic events described in biblical prophecy. They believed the Holy Spirit would soon turn this world over to the Antichrist, a diabolical world leader who would preside over an awful holocaust in which those true believers who had not already been raptured to heaven would suffer interminable tribulations.

But just when all hope seems lost for those still on earth, premillennialists taught that Jesus would return with an army of saints to defeat the Antichrist at the literal Battle of Armageddon. Jesus’ victory will pave the way for God to establish a millennium of peace and prosperity, a new heaven and a new earth.

In the first part of the 20th century, premillennialism spread slowly among Protestants. But World War II, the detonation of atomic bombs and a Cold War nuclear arms race made Americans like Lindsey all the more aware that the world could end in an instant.

After graduating from seminary in the 1960s, Lindsey moved to California, where he joined the ministry Campus Crusade for Christ (now Cru) and began working with students at UCLA. He lived in a communal home called the JC Light & Power House (JC for Jesus Christ) and was immersed in the Jesus people movement, the born-again version of the counterculture in which Jesus was celebrated as the first hippie. He also began writing a book with co-author Carole Carlson on the second coming of Jesus.

“The Late Great Planet Earth” by Hal Lindsey and Carole Carlson. (Courtesy image)

In 1970, Lindsey and Carlson published “The Late Great Planet Earth.” Filling the text with silly puns for chapter titles and subtitles, including “Russia is A Gog,” “Scarlet O’Harlot” and “Sheik to Sheik,” they applied biblical prophecy to current events, emphasizing the global influence of the USSR and China, the increasing power of Arab nations and the creation of the European Common Market. But more than anything else, Israel occupied the center of Lindsey’s analysis. He believed the creation of the state of Israel and Israel’s capture of Jerusalem during the Six-Day War represented clear signs of the fast-approaching end of days. He expected to next witness the reconstruction of the Jewish temple, probably on the land currently occupied by the Dome of the Rock.

These beliefs have made American evangelicals like Lindsey some of Israel’s closest champions in the United States. However, they often see Jews as little more than pawns in their grand, apocalyptic, end-times, biblical scheme. The Bible, evangelicals insist, predicts that the reborn Jewish nation will eventually extend to the same boundaries as David’s ancient kingdom. As a result, they dismiss calls for an independent Palestinian state or any kind of two-state solution. They are sure no American policymaker will change God’s promise that Jews will inhabit the land of their fathers.

But after Jews reestablish the full kingdom of Israel, evangelicals expect history to take a dark turn. Once Israel’s Christian allies have vanished in the Rapture, Jews will suffer horribly at the hands of the Antichrist, which will inadvertently provoke a second Jewish holocaust.

Lindsey offered a rough date for the Rapture based on Jesus’ promise that when certain signs appeared the “generation” that witnessed them would not “pass till all these things be fulfilled” (Matthew 24:33-34). The “rebirth of Israel,” the evangelist informed readers, marked the fulfillment of this prophecy. “A generation in the Bible,” Lindsey continued, “is something like forty years. If this is a correct deduction, then within forty years or so of 1948, all these things could take place.” Lindsey expected the Rapture to happen by 1988. “Late Great” is still in print and has not been updated or revised, although as Lindsey went through multiple marriages and divorces his author photo and acknowledgments changed accordingly.

As evangelicals digested the book, sure that it helped them make sense of current events, its popularity grew. Sensing an opportunity, editors at Bantam Books, a commercial publishing house, bought the rights for the mass market edition of “Late Great” from Christian publisher Zondervan. Bantam placed it in newsstands, at airports and in grocery stores, leading to explosive sales. It became the bestselling nonfiction book of the 1970s, with tens of millions of copies in print today. In 1979, Orson Welles even narrated a popular film version of the book. It made Lindsey millions of dollars, which he occasionally flaunted.

Lindsey never recaptured the success of “Late Great,” but he rode the premillennial wave that he had helped form to the end of his life. He wrote more books on the coming apocalypse, developed a television show and took to the internet to pitch his theology.

Other evangelicals followed Lindsey down the road to Armageddon. They kept readers up to date with analyses of the unremitting global turmoil and chaos that defined their eras. San Diego minister Tim LaHaye laid out an argument in 1972 for an imminent second coming in “The Beginning of the End.” Two years later Dallas Theological Seminary President John F. Walvoord published “Armageddon, Oil and the Middle East Crisis.” In 1972, apocalypticism found another innovative expression in the film “A Thief in the Night,” which became a cult classic. Christian rock pioneer Larry Norman’s track “I Wish We’d All Been Ready” (for the Rapture) haunts the film. Even Billy Graham got in on the action, writing more books on the end times than on any other topic. More recently, LaHaye and co-author Jerry Jenkins wove premillennialism into fiction in their bestselling, 16-volume “Left Behind” series.

“Late Great” made apocalyptic evangelicalism palatable to the broader American public, and even Ronald Reagan purportedly studied it. The book opened many doors for Lindsey, who claimed to do consulting work on global politics for both the Pentagon and the Israeli government. His success also gave him a platform for expressing his political views. Like most other premillennialists, Lindsey was a staunch conservative and he parroted the language of the new religious right.

After 9/11 Lindsey wrote a distorted, fear-mongering recap of the history of Islam. His anti-Muslim bigotry drove executives at the Trinity Broadcasting Network to temporarily cancel his weekly “International Intelligence Briefing” prophecy show. During the first Trump administration, he called the president “God’s man for this time in America,” while chastising Democrats.

Hal Lindsey was never an institution builder and he never collaborated with other Christian leaders. But he inspired a generation of evangelicals to act on the conviction that the end was near, and he fostered in them a sense of urgency and certainty and a vision of the world defined in absolute terms. While other Christians emphasized patience, humility and willingness to compromise, Lindsey taught that true believers were engaged in a zero-sum game of good-versus-evil. They were a faithful remnant surrounded on all sides by the devil’s minions, while the Antichrist lurked somewhere out in the shadows.

Lindsey is gone, but the ideas he popularized will continue to shape evangelicalism for generations to come.

(Matthew Avery Sutton is a Guggenheim Fellow, is the author of “American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism” and is the Berry Family Distinguished Professor in the Liberal Arts at Washington State University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS or WSU.)