LOS ANGELES (RNS) — In mid-October, the day before the one-year anniversary of Hamas’ attack on southern Israel, activists in Chihuahua, Mexico, strung a banner bearing a pro-Palestinian message from a parking garage to the Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Chihuahua.

In Spanish, the words “My son is Palestinian” were emblazoned in bold red letters below a depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the brown-skinned virgin and patron saint of Mexico, wearing a black-and-white kaffiyeh and a cloak decorated with tiny watermelons, both symbols of Palestinian resistance.

To one of the persons who created the banner, who asked to remain anonymous, there was no better way to evoke reaction than by communicating through the Virgin of Guadalupe. “We wanted to reach people’s hearts. The Virgin is a figure of authority. It’s as if she’s saying, ‘My children, don’t be indifferent,’” said the activist.

As Israel’s war in Gaza continues, the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, whose feast day falls on Dec. 12, has emerged as a symbol of Palestinian support among Latino activists and artists in the U.S. and Mexico. More than 44,000 Palestinians have been killed so far in the war that began after Hamas militants killed some 1,200 people and abducted around 250 others on Oct.7, 2023.

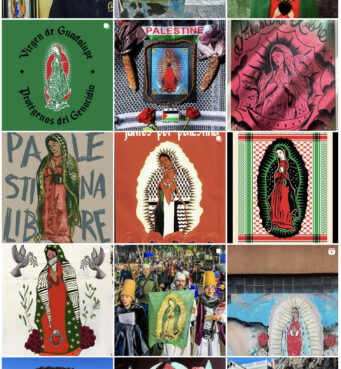

A variety of Palestinian-themed Virgin of Guadalupe artwork on the “Where’s Lupita?” Instagram. (Screen grab)

The art features traditional and interpretative images of the Virgin of Guadalupe fused with watermelons and kaffiyehs, symbols that represent Palestinian identity and resistance. Many of the illustrations are featured on the Instagram known as “Where’s Lupita?,” which tracks global Virgin Mary iconography.

Some illustrations appeared on Instagram as fundraising efforts for UNRWA USA, a nonprofit that raises funds and supports the work of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees.

Gustavo Martinez Contreras, creator of Where’s Lupita?, said artists using Guadalupe’s image in support of Palestinians are continuing a tradition of Chicanos who harnessed the Virgin as a symbol “in defiance against the system.” To Martinez Contreras, these depictions symbolize Guadalupe as “caring for the marginalized.”

Daisy Vargas, a professor at the University of Arizona who specializes in Catholicism in the Americas, sees this artwork as “important interpretations for this particular political and cultural moment,” noting that artists are drawing parallels between the current violence in Gaza and the biblical narratives of Mary as the Palestinian mother of Jesus “who is experiencing the violence of empire in an occupied land.”

Vargas also sees a connection to the story of the apparition in Mexico. “These are symbols that are important within the context of people who have experienced a history of colonial and imperial violence and displacement from their own homelands,” Vargas said.

The feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe marks the Catholic Church teaching that the Virgin Mary appeared to St. Juan Diego, an Indigenous Mexican, on a Tepeyac hill in present-day Mexico City in 1531. The Virgin Mary took the form of a mixed-race woman who spoke Nahuatl, the language of the people that had been recently colonized by Spain, writes art history professor Judith Huacuja.

Daisy Vargas. (Photo courtesy of University of Arizona)

In the 19th century the Virgin was invoked during the Mexican independence movement, when images of the Virgin were emblazoned on banners protesting the Spanish occupation. Today, the Virgin has been used as a symbol of resistance against housing displacement and as a protector of migrants.

“Artists are using the symbol of the Virgin because it’s a powerful symbol of Latinidad,” said Vargas, using a Spanish word referring to Latin identity. “It’s a powerful symbol of Christianity. It’s a powerful symbol of maternal love. … It really asks people to consider what is happening in Gaza, and how it (connects) to their own identity and their own faith traditions.”

“Virgencita Palestine,” by Ernesto Yerena, an artist and printmaker in Los Angeles, juxtaposes the iconic image of the Virgin of Guadalupe against a kaffiyeh-patterned backdrop in red and green, the colors that appear on both the Mexican and Palestinian flags. Yerena sold the prints in January to raise money to fund and distribute “Free Palestine” posters at pro-Palestinian rallies.

“I would say a lot of people who identify as Latinos, Latinas, they would dig this image. They would feel it’s representative of the way we feel,” said Yerena.

Though he grew up Catholic, Yerena said he isn’t religious and he rebukes what he sees as a disparity between the Catholic Church’s wealth and charity work. The Virgin of Guadalupe, however, “has a warm place in my heart because of my grandmothers, my mom. They love the Virgen,” he said.

“I’ll always feel connected to it even though I don’t identify as Catholic,” said Yerena, who identifies as Chicano and Indigenous. Among his great-grandparents, he said, were Yaqui, and Indigenous Mexican people, and a Sephardic Jew.

Yerena learned about “oppressed peoples” solidarity movements with Palestine in his 20s, he said, and soon after began creating art in solidarity with Palestinian people, drawing inspiration from political posters of the Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He said he has been called antisemitic for his work, which he finds ironic, given his family history. “I’m proud of my Jewish heritage,” he said.

A banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe with the words “My son is Palestinian” in Spanish hangs from a parking garage facing the Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Chihuahua, Mexico. (Photo by Raúl F. Pérez Lira/Raíchali)

Catholic Church leaders have been criticized for allowing a Nativity scene featuring a Christ child in a kaffiyah — since removed — in the Vatican’s Christmas display in St. Peter’s Square, and other antisemitism watchdog groups have objected to efforts to merge Palestinian and Christian imagery. (Martinez Contreras, founder of Where’s Lupita?, was fired from his job in 2021 for writing a misogynistic and antisemitic caption that he said was accidentally published by the newspaper he was working for.)

Lizett Carmona, an artist based in Chicago, created a Virgin of Guadalupe draped in a black and white kaffiyeh, with the words “juntos por palestina” (together for Palestine) displayed above the Virgin’s image. With her piece, she’s petitioning for protection of Palestinians.

“I wanted to show solidarity and find some interconnectedness … between me, someone of Mexican descent, and someone from Palestine,” said Carmona.

Her work touches on themes of migration and liberation and features images of police cars on fire and of children selling candy at the border.

Carmona, an agnostic who considers Catholicism integral with her culture, thinks of Guadalupe as “the product of colonialism.” “But then I think a lot of our identity, we are byproducts of colonialism. It’s just not easy to make those rigid lines,” she said.

Her response for critics who accuse her of using Catholic symbols to promote her ideology?

“Of course, that’s what I’m doing,” Carmona said. “This is propaganda. I’m a propagandist. I want you to reflect. I want you to question.

“Not only do I think of (the Virgin of Guadalupe) as a symbol of Catholicism, I think about it as going outside seeing her on tienditas (convenience stores), on graffiti, or on a tattoo of a person. It’s just an image that pertains to so much more of our culture than the religion itself,” Carmona said.