(RNS) — Twenty years ago, Andrew Bauman was part of the problem.

The son of a pastor in the Southern Baptist Convention, Bauman studied religion in college and became a pastor. But privately, his struggle with pornography had infused his spiritual beliefs.

“My pornography use had mixed in with this misogynistic theology that really made women less-than,” he told RNS in a recent interview. But with that realization came transformation. Bauman traded his pastoral vocation for a career as a licensed mental health counselor and interrogated his religious beliefs until, he said, they were more reflective of Jesus.

“As I look at the way Jesus engages women, the way he subverts the patriarchal culture at the time, my faith only grows,” he said.

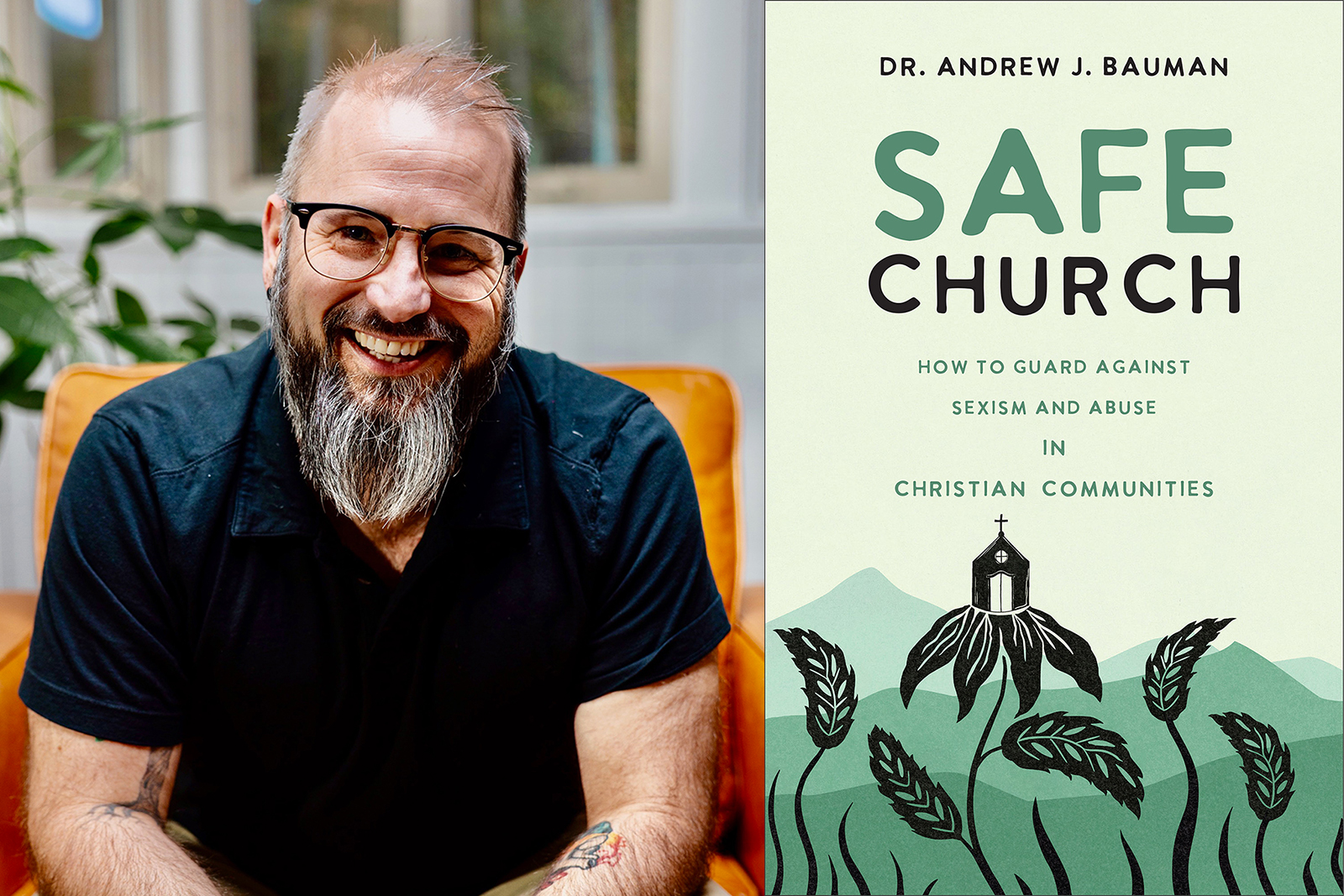

These days, Bauman co-leads the Christian Counseling Center, which specializes in sexual health and trauma, with his wife and co-founder, Christy Bauman. And in his latest book, “Safe Church: How to Guard Against Sexism and Abuse in Christian Communities,” he aims to use his position of influence to invite Christians of all stripes to listen to women and to sit with the reality that there’s an epidemic of abuse and sexism in their faith communities.

RNS spoke to Bauman about male headship, the appeal of Andrew Tate and whether church can ever really be safe. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is your faith background, and how does that inform your approach to this topic?

I grew up in the Southern Baptist church, and my father was also a pastor, a lawyer and a prominent evangelical figure in the ’80s. He also had a hidden life. He cheated on my mom for 20-something years, and that blew up my family when I was 8 years old. My mom experienced this horrific trauma of abuse and spiritual bypassing and had the fear of exposing my father. So, this book is so personal to me because I watched it in my mom’s story. I watched how it impacts my own family.

You surveyed 2,800 women and conducted several in-depth interviews about abuse in Protestant churches. How did you connect with these women, and what surprised you about the survey findings?

I reached out on social media platforms, putting out the survey in the world, and it really caught on. Women are so hungry to tell their stories. They’ve been silenced so long, and they desperately wanted to just tell their story to help other people.

This is probably not a surprise to many women, but the survey found that 82%, which ended up being around 981 women, said they believe sexism played a role in their own church. That’s wild to me. And 62% they said they wouldn’t be surprised if they’d heard a sexist joke from the pulpit. Thirty-five percent said that they experienced some type of sexual harassment or sexual misconduct, or they answered it’s complicated, like, you know, there was a larger story. Almost 78% said their opportunity in ministry had been limited due to their gender.

You write that the church’s reliance on male headship strikes you as more emotional than theological. How so?

People think it’s biblical, but I truly believe it’s a misinterpretation of the text. Women being quiet, learning full submission. I have a whole chapter on problematic biblical texts and how we can interpret it more fully. But truly, I believe we have an epidemic of underdeveloped men. A lot of that’s from the socialization of masculinity. We tell men it’s weak to be emotional. We have so many men who don’t understand intimacy. And pornography has infiltrated the minds of churchgoers. It’s showing up in what I call a pornographic style of relating. For example, if you have a pastor who has a secret porn addiction and he has tons of shame, he’s going to project that onto women.

On social media, there’s a debate about why so many young men are being drawn to the notoriously misogynistic influencer Andrew Tate, and whether it’s due to shortcomings in the church. What’s your view on this?

We want a figure that feels strong, right? So if you feel like a little boy inside, you’re going to gravitate to totalitarian leadership, like Donald Trump and Andrew Tate. We’re working out our brokenness on these figures. And one way to feel tough quick is to sexualize, objectify and make women feel small, so I can feel big, rather than doing the hard emotional labor of healing the wounded place within ourselves. I believe the church has helped promote that by promoting really problematic theologies and teachings that make vulnerable women more susceptible to subjugation.

Your book looks at teachings that can exacerbate the harm women experience in the church. Yet churches that ordain women, reject purity culture, use inclusive language for God and have robust abuse policies also have sexism and abuse. Why might that be the case, and what can these churches do to become safer?

It’s easy to make it black and white: Conservatives do this, and progressives do this. And yet, blind spots are in both camps. At one progressive seminary I know of, the students would go around and just go have sex in all the different areas of school. That was their idea of reclaiming purity culture. And I’m thinking, OK, you’re pushing against shame, but entering into shamelessness is no closer to healing. Not honoring the sacredness of sexuality is also toxic. So, I would say it’s the same message for progressive churches. What are you not addressing in your system that’s still perpetuating some of these things that are causing the problems? We have to deal with what’s beneath and not just fix symptoms.

Many church leaders have the impulse to prioritize reconciliation in the context of abuse. Is reconciliation ever an appropriate response to abuse, and if so, how should it be approached?

I call that weaponizing forgiveness. I’ve heard it time and time again. The perpetrator has tears in his eyes and says he’s sorry. Really, he’s just sorry he got caught. It’s a cheap grace. Action is the apology. We can’t believe what people say. We can only believe what they do. I heard it so much from the women I talked to, that the victim of abuse was pressured to forgive quickly without proper grief or repentance from the perpetrator. Misquoting Bible verses on grace and forgiveness can be just a way to manipulate and to spiritually bypass abuse. They end up making the problem the victim’s fault, retraumatizing them. It becomes a problem about forgiveness, rather than about the actual abuse.

In those situations, moving on is the highest priority. They don’t want their church to be exposed. What if the highest priority was being present with the victim?

How do you respond to church leaders who point to dwindling resources, overworked volunteers and burnout as barriers to implementing robust safeguarding and misconduct policies?

If you actually start doing this, and you create safety, people will be drawn to that, and that will create more financial support. Because if you start the conversations that matter, and you actually teach women to trust their intuition and their gut, that’s going to be attractive. Rather, we’re seeing record numbers of people leave the church.

The title of your book is “Safe Church,” but as you acknowledge throughout your book, the church is made up of imperfect people. Can any church really be safe?

I believe it’s not a final destination. It’s an ongoing process. So, can you ever finally reach safety? I don’t think so. But can you begin to implement yearly abuse prevention training? Can you familiarize yourself with policies and reporting procedures? Can you invite open dialogue in your churches? Can you increase diversity in leadership positions? There are always steps churches can take.