VATICAN CITY (RNS) — In the late 1100s, an Irish priest and his assistant traveling south from Ulster stopped for the night. As they sat by their campfire, a wolf approached and spoke, telling the astonished travelers not to be afraid. Every seven years, he explained, he and his wife were damned to “quit entirely the human form,” and assume that of wolves. The wolf brought the priest to his ailing wife, begging him to give her Communion before she died.

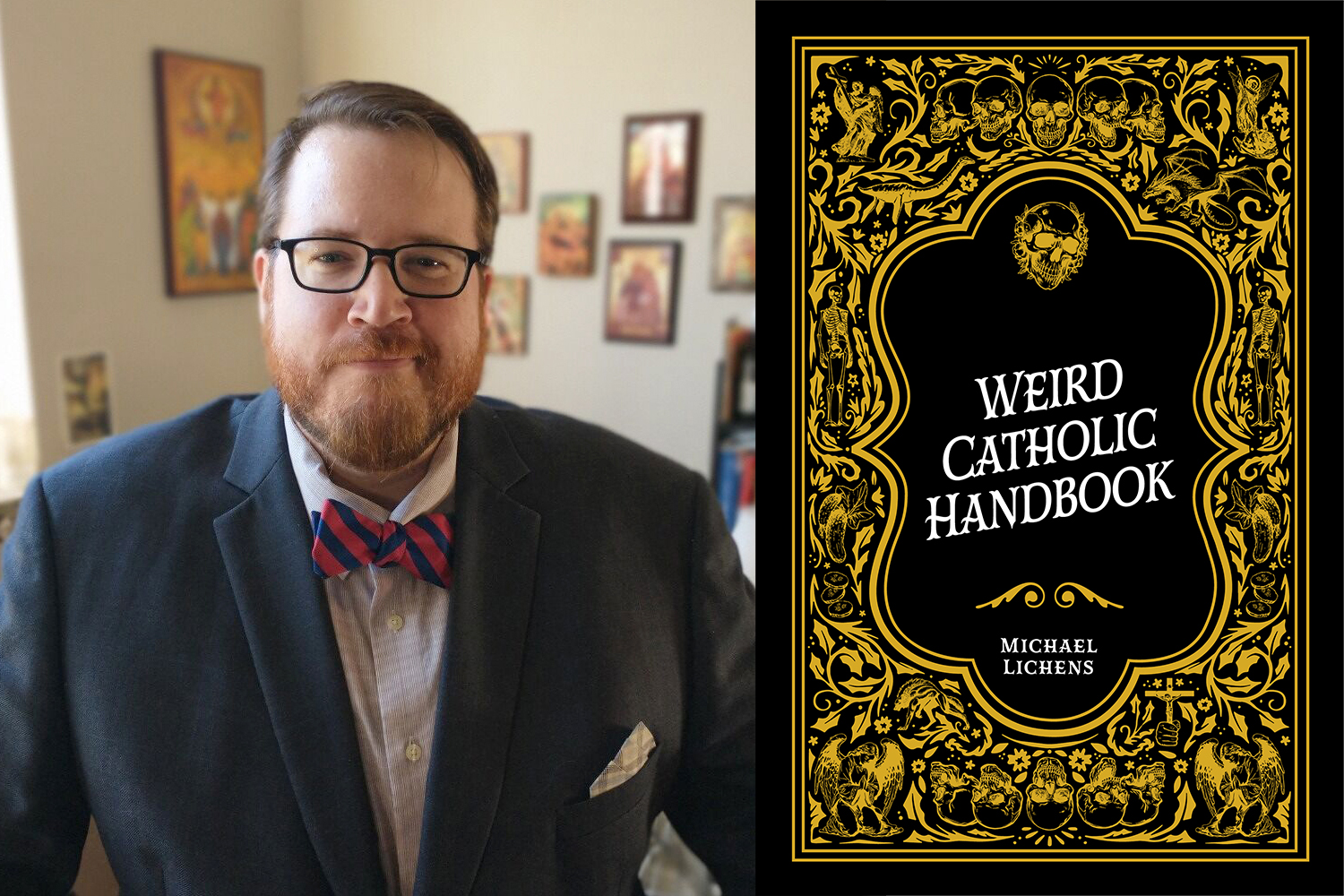

This strange tale, originally told by Gerald of Wales in his 12th century text “Topographia Hibernica” (Topography of Ireland), is one of many related with relish by Catholic editor and writer Michael J. Lichens in his new book, “Weird Catholic Handbook.” Drawing from a wide array of sources, Lichens brings together mysterious tales of supernatural activity and customs from the Catholic world, offering accounts of werewolves, ghosts, mummies and flying saints and delving into little-known tales that defy belief.

The pleasure of the book, however, is also in Lichens’ ability to see the everyday comfort of even the weirdest lore. Gerald of Wales’ story, he writes, “demonstrates how wild and weird the world could be” in bygone days, but also “reminds us that although the world can be savage and strange, there is grace enough that even werewolves can be redeemed.”

From dragons and the Loch Ness monster and saints fixed with heads of wolves, Lichens shows how deeply the Catholic tradition intertwines with the paranormal. Many of the stories revolve around the Catholic understanding of death, or memento mori, understood as the reminder that all things must die. He writes of the morbid relics of unnamed saints whose remains were covered with precious stones, jewels and even crowns.

Lichens also celebrates “catacomb saints” — katakombenheiligen in German — which became very popular during the Counter-Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries as a uniquely Catholic art form aimed at celebrating the life, and death, of saints and martyrs. The most spectacular, he says, are found in Melk Abbey, Austria, where the bejeweled remains of St. Friedrich, in a relaxed pose, appear to be art for art’s sake.

“The relics of St. Friedrich in Melk Abbey, for example, arrived at the abbey without a name, and the monks simply gave him one familiar to their own culture and time,” Lichens writes. “Now the remains of this anonymous martyr are venerated under that name in a stunning monastic church where they are admired by tourists while venerated by monks and pilgrims.”

Offering itineraries to find the places and remains of the strange occurrences of Catholic history, the book is a guide not only to the strange but to moments and places that can give a modern believer’s faith dimension.

“What I find with these places, like going to an ossuary or a church that displays mummified remains of the monks or things like that, it really takes you out of the everyday,” Lichens said in an interview. “In my experience, some of these places are almost a spiritual gut punch of different ideas.”

That includes, he said, tales that capture the church’s obsession with death. He tells the story of the Wizard Clip, a ghostly infestation in what is today Middleway, West Virginia, in the early days of the United States. According to firsthand accounts and letters, a Catholic traveler from Ireland died at the house of Adam Livingstone, a Lutheran, without last rites and began haunting the family after his death.

“The Wizard Clip gets its name from the phantom sound of shears opening and shutting that the family and neighbors would often hear before finding crescent moon shapes cut into their clothing or household linens,” Lichens writes. “Even items secured in pockets or trunks would get attacked by the invisible shears.”

The Rev. Demetrius Augustine Gallitzin, a priest currently being considered for sainthood, was called in with a colleague to perform an exorcism in the Livingstone home. The family eventually converted to the Catholic faith but according to some accounts were haunted by the voices of spirits suffering in purgatory until the end of their lives.

“As I dug deeper, I realized it was like this great mix of Appalachian folklore and Catholic theology, something you just don’t see a lot,” Lichens told RNS. “It happened in the 1790s, right at the beginning of the United States republic. It’s probably the first poltergeist story in the United States,” he added.

Incredible feats of saints and would-be saints are featured heavily in the book, whether they are resurrecting dead children in pickle barrels, appearing in two places at once or casting out snakes from Ireland. The 17th-century St. Joseph of Cupertino stands out for his ability to levitate and even fly in moments of spiritual rapture. According to accounts collected by Lichens, St. Joseph flew several feet in the air after kissing the hand of Pope Urban VIII and would not come down until his superior ordered him to.

“Everyone has a dream in which they can fly, but some saints actually get to experience it. Levitation simply defies the law of gravity. It is a sign of God’s power over nature, and the people who witness it are often struck in disbelief,” Lichens writes, adding that even the Inquisition doubted the mystics’ incredible feats of levitation at the time, but had to admit there was not trickery involved.

The point, however, is not the veracity of every story Lichens tells, but what Catholic folklore tells us about our own place in the divine scheme: “More than anything,” he said, “it excites the imagination. Suddenly seeing these things takes our everyday faith and lets us think about it in much bigger terms: If the werewolves can even be saved, what does that say for us?”