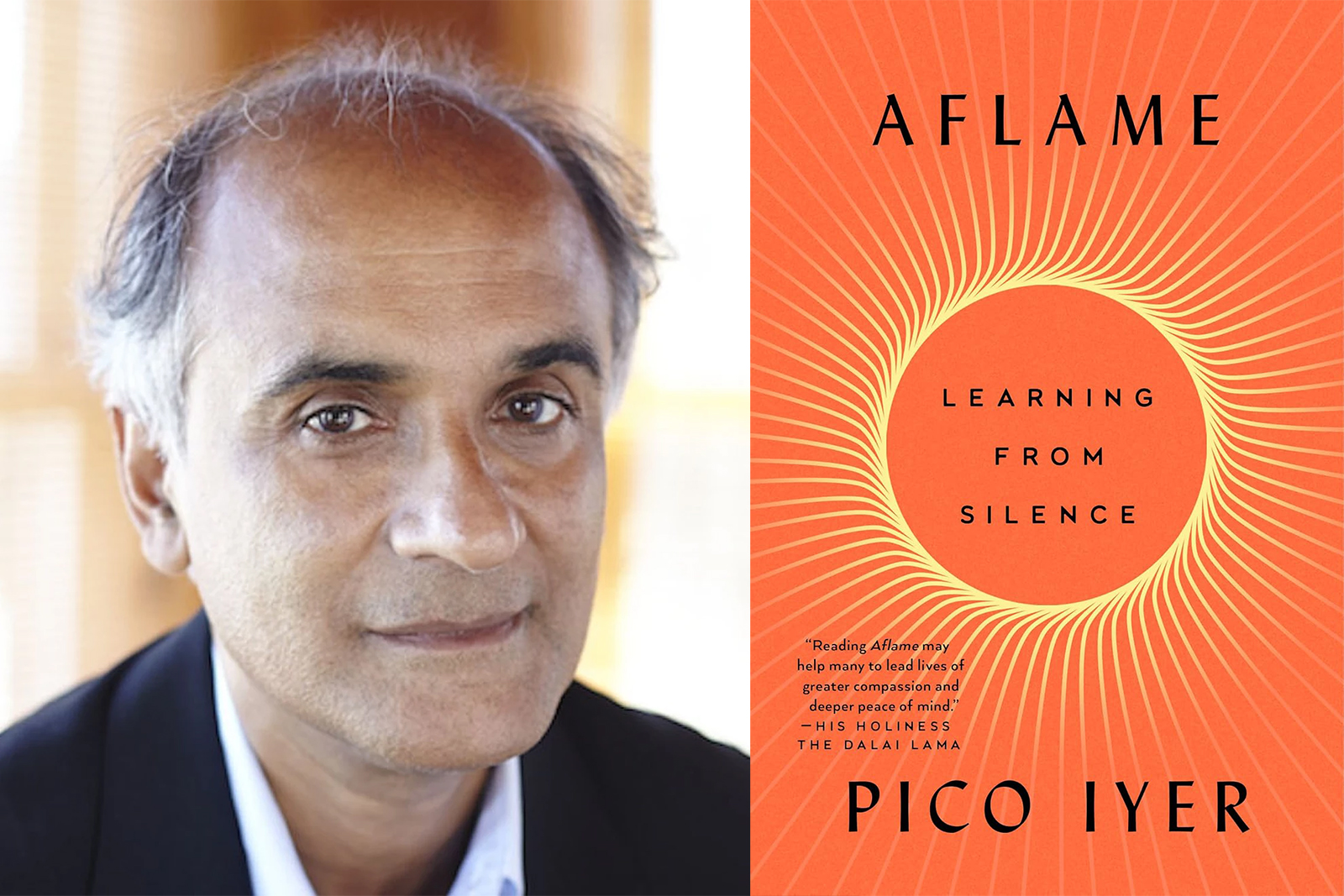

(RNS) — Pico Iyer is no stranger to the disaster now visiting residents of Los Angeles. In 1990, a wildfire burned down his family home in Southern California and everything inside. In his latest book, “Aflame: Learning From Silence,” the prolific novelist, travel writer and essayist tells how he found solace through more than 100 visits over three decades at the New Camaldoli Hermitage, a Benedictine monastery “surrounded by fire” on the state’s Big Sur coastline.

Through the Catholic and Buddhist teachings of the monks, Iyer finds a “language of silence” that transcends doctrinal boundaries and a path to finding stillness amid constant tumult.

Iyer recently discussed the takeaways from his book with RNS. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your parents were philosophers and professors of comparative religion. How did that shape your thoughts about religious belief?

Growing up in Oxford, England, Tibetan monks would appear suddenly, sent by the Dalai Lama. My father sailed to India to meet the Dalai Lama just as soon as he came into exile and brought a little photograph for me from the Dalai Lama. Because my parents had grown up in British India, they (also) knew the Bible backwards and forwards and could tell me about Buddhism and Islam and Judaism and things that I don’t think most little boys in Oxford in 1960 were hearing about. Also, because they were theosophists, they knew all the philosophical background for the traditions, too.

I think my parents were preparing me perfectly for a global world and a global identity. Sometimes people notice how I have four names — my official name is Siddharth Pico Raghavan Iyer. My first name is the name of the Buddha, and Pico is in honor of the great Italian Renaissance heretic, Pico della Mirandola. Raghavan is (after) my father, a theosophist, and Iyer is a Hindu name. It was an ideal preparation for the life to come.

What were your thoughts when you heard about the recent L.A. fires?

Tragically, I wasn’t surprised. Fire is really our most loyal and constant visitor in these dry hills. When fire wiped out our house in 1990, it was quite rare. Now, there are sometimes two or three in a year. When I gave the book the title “Aflame,” it wasn’t coincidence. Because fire is such an important spiritual force, it seemed important to get these two things into collision: the flames that the monks so beautifully exemplify, and the flames rewriting our lives.

How can we all make peace with living on unstable, shaky ground?

All the way through my 20s I was as ignorant and maybe as arrogant as many of us. I made my plans, I mapped out my next eight years of my future and I thought, “Oh, the world is going to accommodate me and allow me to proceed along my merry path.” The fire that destroyed our house and stripped me of everything, including, really, most of my dreams of becoming a writer — I lost my next three books, I lost that picture of the young Dalai Lama. But it was a wake up call that the world and life was not always going to accommodate me. So that fire was a very good thing in disrupting me out of my complacency.

Since then, of course, I’ve been much more wary, much more eager to make my peace with these elements. I started keeping all my notes in a safety deposit box. I started living much more simply, realizing I couldn’t hold onto material things, and therefore shouldn’t be so dependent on them. I remembered that you can’t hold onto precious things like this, that a photo is never going to last, ever. The important things are the values that photo stands for, and the teachings it might offer. Those can stay with me when the photo itself was gone.

How can someone be realistic about suffering, yet remain hopeful?

That’s the heart of it. That’s the heart of the question facing us all and I think it’s the heart of my writing, which is how to keep hope and realism alive in your heart. If you give up hope, you’ve given up on life, essentially. The Dalai Lama gives us a model of how not to be defeated by circumstance. He has suffered more than anybody I know. He’s lost 13 of his 15 siblings, he’s been an exile for 65 years and all he radiates is confidence and laughter and warmth. That’s true of my Benedictine monk friends in Big Sur who are constantly having to evacuate, their communities getting smaller, they’re mostly very elderly, but they never lose faith.

You’ve said belief matters less than action. Why do you say that belief belongs to the peripheral, not the immediate, silent self?

The important thing I should add is that, of course, action often flows from belief. The Dalai Lama practices compassion because he’s committed to the Buddha’s teachings. My Benedictine monk friends radiate confidence, probably because they’re sure that God will protect them. But I do feel that belief is what’s cutting the world up into parts. I believe something different from you, and so suddenly we’re divided by that. We have all that in common: Belief is taking us apart. But there’s something else in human experience, and in silence, that’s bringing us together.

Pico Iyer, right, in conversation with author William Green at Asia Society in New York, Jan. 22, 2025. (RNS photo/Richa Karmarkar)

What surprised you about the monastery?

The biggest surprise was the monks are so open-minded. They’re not holier-than-thou, but very down to earth. When I stay in the cloister with them, there’s one person training to be a rabbi, another who’s practicing Buddhism and others who have no religion at all, and they’re welcoming to all of them. The other beautiful surprise was that whenever I meet anybody along that road, I feel closer to them than anybody I meet on Fifth Avenue or on the street here in Santa Barbara. We’re joined by some longing for silence, something deep inside us. So instantly, I trust and respect them.

You’ve said that silence lives in a world beyond division. What should we learn from silence or solitude?

I read recently from one of the Hindu Scriptures, “If your mind is silent, abiding joy is yours.” Many of us have this constant chatter in our heads. When we’re freed from that chatter, suddenly the world is a much better, truer place, a less divided place. The silence I describe in the book is not just that of a quiet place. If you go to a monastery, the silence is not just the absence of noise — it’s this positive, calming presence created by years of prayer or meditation.

I just ran into a sentence where the Buddhists say, ‘Thoughts cannot penetrate the vast blue sky.” Even though I had a strong analytical training, and I live by words, I think I’m happiest when the words and the thoughts fall away. I think all of us are. When we think about the peak moments in our life, they’re often the times when we’ve been stripped of all words, when we fall desperately in love or in speechless wonder in a miraculous landscape or even sometimes when we’re scared, and we have no words to bring to it. It’s something much larger than our lives.