(RNS) — When I was a freshman at a Jesuit high school in Los Angeles, my English composition teacher drummed into us the importance of unity, emphasis and coherence. Pope Francis’ new memoir, “Hope: The Autobiography” (Penguin/Viking), ghost-written by Carlo Musso, strikes me as a luminous example of these skills. What keeps jumping out at you is the extraordinary integration of human and spiritual values, beauty, intelligence and art revealed throughout Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s long and endearing life. Finely written and superbly translated from the Italian by Richard Dixon, the book exudes the verve we have come to expect even in the 88-year-old pope. In 25 relatively brief chapters averaging about 15 pages each, the pope presents an engaging synthesis of deep and persistent currents of feeling, thought and colorful anecdotes that began to blossom early in his life and seem to just keep producing fruit.

Francis focuses on everyday human experience to give us the deep sources and the tangible outcomes of his own most deeply held values. He describes and richly illustrates those lived experiences with apt metaphors, literary allusions and artistic references, especially to movies. Numerous, well selected and some rare photos with informative captions are included that add significance and sizzle to the pope’s flowing narrative. Drama and action lurk everywhere in what amounts to a rather thrilling, if at times dangerous, life. For example, during the General’s Dirty War in Argentina that could get you tortured or just “disappeared” in the murky waters of the Rio de la Plata. Maneuvering his way later in the Vatican’s political labyrinths as cardinal archbishop of Buenos Aires and subsequently bishop of Rome is arguably just as risky and daunting as anything he had to face in Argentina.

The spirit that animates Bergoglio’s life fits well into Jesuit spiritual writer Walter Burghardt’s intriguing definition of Christian spirituality as “a sustained, loving look at the real.” Pope Francis here takes a prayerful, loving and playful gaze at his lifetime, including his family, and many historical events. He doesn’t flinch but offers his memories with all the horror and beauty that accompany them. There is nothing naïve or romantic about this pope’s awareness and assessment of good and evil. Some might criticize that he does not give examples of his errors but frequently mentions that he made plenty of them, especially when he was younger and had assumed heavy responsibilities as leader of the Jesuit order in Argentina.

Persistent themes emerge and reemerge throughout the text. One is the powerful influence of popular culture, religion and spirituality on his worldview — owed in great measure to his Italian working-class stock and to his exposure to the poor and marginal classes of Latin America. Another recurrent theme is his lifelong passion for politics understood through his concern for public policy and its effects on the concrete conditions that deprive the most vulnerable of life, liberty and human dignity. He confirms what his biographers have already noted: that he first became aware of his love for politics — what Pope Benedict XVI called “social charity” — as a young man through friendship with his chemical laboratory mentor, Esther Ballestrino de Careaga, a kind and courageous refugee from Paraguay, and a Marxist. While he did not agree with many of her political views, he deeply admired her passion for social justice and later heard of her torture and death at the hands of the military dictatorship.

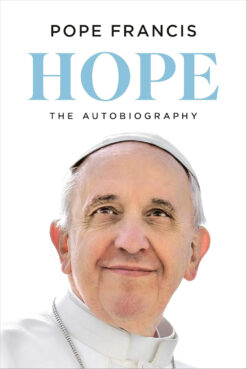

“Hope: The Autobiography” by Pope Francis. (Courtesy photo)

Much of what we read in Francis’ autobiography has already been well documented by writers such as Austen Ivereigh, but what we know is now viewed from the lens of Bergoglio’s Ignatian spirituality and Christian humanism. Since two premises of the Ignatian way are that God can be found in all things and that God’s love is incarnate, the pope imbues his lived experiences, good and bad, with large doses of compassion, mercy and love. He tells the story of his impatience with a beloved priest and an unexplained failure to accompany another priest as he was dying. Bergoglio’s life makes it clear that he really does believe that “the name for God is mercy,” as the pope insists in one of his earlier joint publications with Andrea Tornielli. And this image of God as first and foremost merciful is the key to the autobiography’s title, “Hope.”

The final chapters beautifully develop the theme that has been lurking in the shadows from the beginning. Faith generates hope for Pope Francis because he believes in, loves and chooses to follow day by day the risen Jesus encountered on the road to Emmaus, who will return in glory. This hope in theology is called eschatological because it refers to the end time, the Second Coming of Christ. Such a deep-seated faith, hope and love makes “all things possible” (Romans 8:28) and goes a long way in answering the question about the sources of the steely tenderness underlying Pope Francis’ storied life. Here the key to understanding his legacy and its irreversibility may be found.

With the publication of this autobiography, Pope Francis cements his monumental project of demystifying the papacy. This memoir presents Jorge Mario Bergoglio as a man of real substance who has the courage and maybe even more than a little audacity to tackle one of the oldest traditions in Christianity. Without dismissing or diminishing the Petrine ministry, this reform pope in this well-crafted narrative has sought in small and sometimes larger ways to demythologize that ministry in ways that contribute to the church’s synodal reform.

Synodality means retrieving the church’s horizontality, which requires modifying the excessively hierarchical, vertical elements and rigidity that do not foster the co-responsibility and participation of all the faithful necessary for a church seeking to be evangelizing in its entirety and reaching out in search of communion with other Christians and indeed with all humanity. So it is that Pope Francis informs us tellingly that he loves this quotation attributed to Gustav Mahler: “Tradition is not the worship of ashes; it is the preservation of fire.”

(Allan Figueroa Deck is a Jesuit priest and Distinguished Scholar of Pastoral Theology at Loyola Marymount University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)