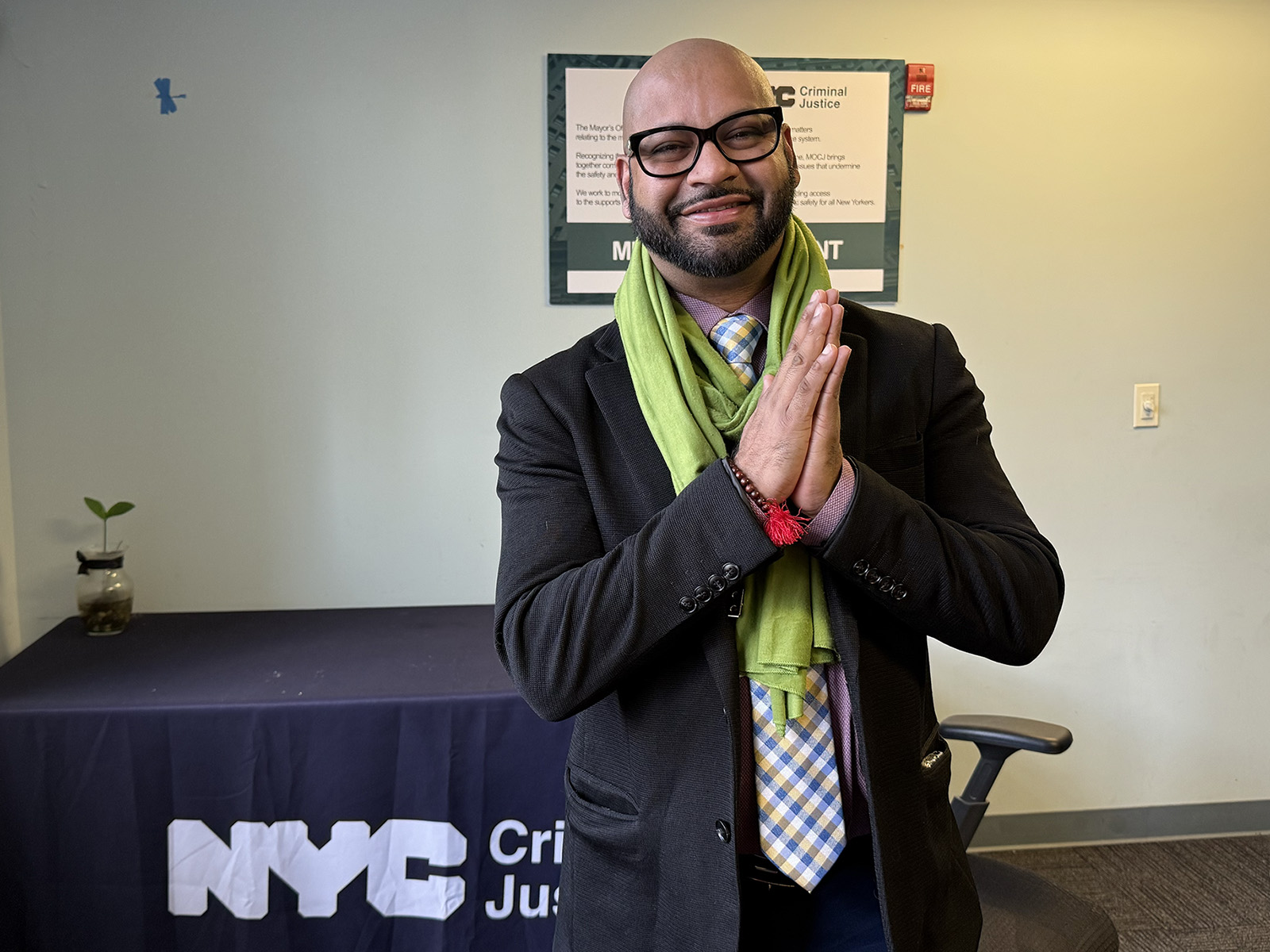

NEW YORK (RNS) — It’s not every day you see a city employee with the credential “karmacharya” attached to his name.

The Hindu title, from the Sanskrit for “one who performs righteous actions,” was bestowed upon Vijah Ramjattan, executive director of New York City’s Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes, by his guru several years ago.

Ramjattan, 44, finds the title especially fitting. “My guru knew my ancestors, who also worshipped God through community service, through seva (a Dharmic term for selfless service), through finding ways to serve humanity,” said Ramjattan. “He said, ‘It’s in your genes, it’s in your DNA, that your lineage has always found ways to serve.'”

When New York Mayor Eric Adams appointed Ramjattan in January, the mayor called him “uniquely qualified to hit the ground running” as hate crime czar.

Though Adams noted that hate crimes in the city have steadily decreased each year, according to the New York state comptroller, the state has seen a “concerning surge” in reported hate crime incidents over the last five years. The most common bias reported in New York state in 2023 fell under the category of religion, with most targeting Jewish New Yorkers.

Adams cited the upswing in explaining why he fired Ramjattan’s predecessor, Hassan Naveed, in April of last year. “You’re given a responsibility in a role, you’re in charge of hate crimes. I’m seeing an increase in hate crimes,” Adams told reporters when asked why Naveed was terminated, referring to a jump in incidents after the Hamas attacks on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. (Naveed maintains he was fired because he is Muslim and has said he plans to take legal action against Adams.)

New York City Mayor Eric Adams speaks during an interfaith breakfast event in New York, Jan. 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Born in Trinidad before immigrating to Brooklyn with his family in 1996, Ramjattan has been a leader since starting a Caribbean Students’ Association in high school. He has worked as a Hindu chaplain at Queens public hospitals and a mental health counselor at Rikers Island and founded a nonprofit, the United Madrassi Association, which organizes parades and cultural celebrations and Dharti Amma Days, when volunteers clean up beaches in honor of a goddess associated with the Earth and fertility.

Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s well-known dictum, “Be the change you wish to see in the world,” Ramjattan sees himself as “devotion in motion,” taking his Hindu faith beyond the walls of his mandir.

Ramjattan, whose parents sent him to vacation Bible school at Pentecostal and Baptist churches as a boy and taught him to make the traditional Trini sweet Sawine for Eid, sees the same charge for people of all faiths. “We spend 10% in the home of worship and 90% out in the community — serving and finding Krishna in the homeless people, finding Christ in the one who’s hungry, seeing Allah in the people who are starving on the streets,” he said.

The most ethnically and religiously diverse city in the world, said Ramjattan, can use his approach to hate crime prevention, characterized by his pluralistic Hindu worldview.

“That background aids heavily in me being able to break the walls down and build bridges, and to take down the misconceived notions of what people think, what the media is saying,” said Ramjattan. “‘No, I want to talk to you. I want to engage with you. Tell me more about you.’ So when I go and I speak to my Jewish friends, I’m like, ‘Oh, I understand. I can relate to you.'”

The New York City skyline behind the Brooklyn Bridge. (Photo by Arthur Brognoli/Pexels/Creative Commons)

Adams noted Ramjattan’s broad experience of faith in appointing him. “New York City is the greatest city in the world because of our extensive diversity, and to stamp out hate wherever it rears its ugly head we need a leader that will help ensure that New Yorkers have the tools needed to be part of the solution,” he said.

To encourage dialogue, Ramjattan plans to bring the work at the grassroots level, he said, “to the blocks, the temples, the churches, in the community centers and in the local precincts.”

“We need to go to the communities and say, ‘Hey, do you know this office exists? Here’s what a hate crime is.'”

Hate, Ramjattan said, looks different for every community, showing up here as a spoken slur, here as a graffitied symbol. To understand these nuances, said Ramjattan, officials must see “past the titles and labels of male, female, Christian, Hindu or Jewish, and seeing that everyone is allowed to be who they are.”

It was only when his family arrived in Brooklyn, he said, that he first heard the idea of racism. Besides difference of color, he saw how his Hindu community perpetuated caste hierarchy, mistreating members of the Madrassi community, descendants of a South Indian worship tradition of Goddess Kali.

That experience is behind his founding of the United Madrassi Association in 2017, despite coming from the relatively privileged Vaishnava Hindu tradition. He said he has faced backlash because of his attempt to break the silence about their treatment. The group has provided food for Muslim migrants in the Bronx, as well as clothing, food and care packages to nearby homeless people, “all in the name of faith,” he said.

As his own seva, he opens his home every month to an interfaith prayer service, allowing the homeless to “come as they are” to enjoy a hot meal. On his altar, he makes room for north and south Indian deities, Jesus Christ, the Islamic crescent and star and the Star of David, along with Vodou symbols and African rain sticks. “It looks like a little U.N.,” remarked the man fighting hate in the country’s largest city.

“I just see various expressions of love for whatever they call God,” he said. “And I embrace that.”