(RNS) — If “The Benedict Option” was Rod Dreher’s book of “woe” — a lament over the collapse of Western civilization, shifting sexual norms and the encroachment of wokeness — then his latest, “Living in Wonder,” published last fall, is his “woo” book: It’s what happens when a culture warrior puts down his sword long enough to gaze up to the heavens.

“The world is not what we think it is,” writes Dreher. “It is so much weirder. It is so much darker. It is so, so much brighter and more beautiful. We do not create meaning; meaning is already there, waiting to be discovered.”

It might be little wonder to many of us that Dreher’s “Living in Wonder: Finding Mystery and Meaning in a Secular Age” joins a collection of recent books meant to help us find awe amid burnout, loneliness, addiction to screens and a suffusive flatness of the soul.

In 2023’s “Enchantment: Awakening Wonder in an Anxious Age,” Katherine May pointed us to joy in the natural world. “Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life,” from psychologist Dacher Keltner, from the same year, gave readers eight pathways for experiencing the titular emotion, which he defines as “the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your current understanding of the world.”

Australian journalist Julia Baird’s memoir “Phosphorescence” speaks to and for people who “don’t attend church or adhere to any particular religion,” but rather “congregate on beaches, in forests and on mountaintops to experience awe and wonder.”

The malady these books are intended to remedy is one that Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor has written about extensively, most notably in his 2008 book “A Secular Age,” which traces how belief in God went from being axiomatic to merely one option among many.

Taylor writes that the premodern world was “enchanted” — good and evil spirits were real and acted directly upon us. Humans were “porous,” with no division between the physical and spiritual, or the individual and the communal. “God figures in this world as the dominant spirit, and moreover, as the only thing that guarantees that in this awe-inspiring and frightening field of forces, good will triumph,” he wrote.

Today, people in the post-Enlightenment West are no longer porous but “buffered.” They perceive themselves as no longer subject to nature’s forces, controlling and utilizing the material world with cool reason. This retreat into the rational mind means Westerners are largely walled off from “whatever lies beyond this ordered human world and its instrumental-rational projects,” Taylor claimed. The cost is a “wide sense of malaise at the disenchanted world.”

A shallow reading of “A Secular Age,” which expands on ideas of Max Weber, the German sociologist who gave us the “Protestant ethic,” would stop at the conclusion that Westerners are now atheists. Taylor would clarify that, though we are post-Christian, we are certainly not postspiritual.

Dreher, whose coverage of the Catholic abuse scandal as a journalist led him out of Catholicism into Eastern Orthodoxy, comes to the topic of wonder from a deeply religious perspective. He is best known for his 2017 book calling for Christians to retreat from secularist, individualist and LGBTQ activist culture, modeled on Pope Benedict XVI’s suggestion that a smaller, more doctrinally cohesive church was better than a bigger, flabbier one.

In 2020 he followed up with “Live Not by Lies,” which sounded the alarm that “a progressive — and profoundly anti-Christian militancy — is steadily overtaking society … there is virtually nowhere to hide” from identity politics and Marxish wokeness.

Since then, Dreher has faced a series of upheavals. After losing funding for his popular blog at The American Conservative, he decamped to the Danube Institute in Budapest, where he has cozied up to Hungarian President Viktor Orbán, raising concerns among fellow conservatives. He also went through a divorce, the devastation of which he writes about in “Living in Wonder.” While culture war strains are still present, the book strikes an introspective note, as Dreher encourages readers to reawaken to God through prayer, beauty and openness to unseen spiritual realities.

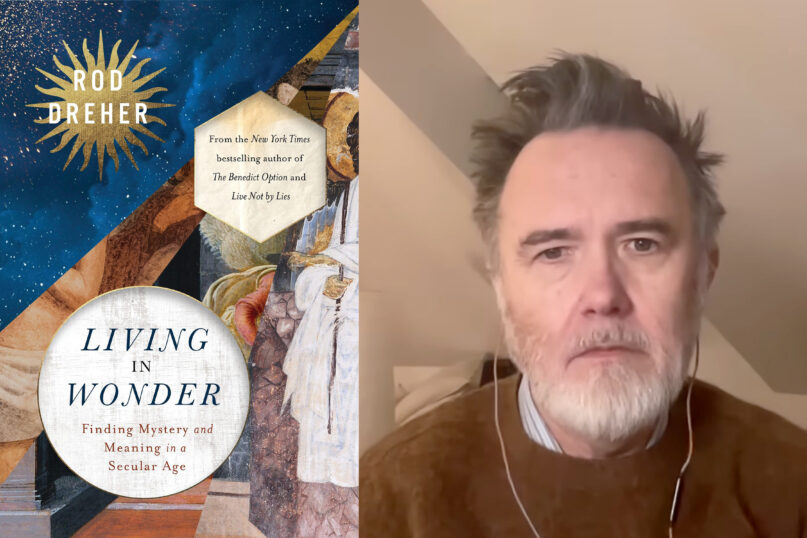

“Living in Wonder: Finding Mystery and Meaning in a Secular Age” cover and author Rod Dreher. (Courtesy image and screen grab)

He finds evidence for this unseen realm in stories of demonic possession and UFOs. He devotes an entire chapter to the latter, leaning on eclectic sources such as scientist Jacques Vallee and the Orthodox priest Seraphim Rose to posit that aliens are malicious beings who want to enslave and destroy humanity. Dreher warns readers against “dark enchantment,” such as tarot cards, psychedelics and witchcraft, which he links to “progressive political commitments, especially around feminism, environmentalism, and queer activism.”

Several portions of the book veer conspiratorial; he quotes an exorcist who posits that the occult is “supported by the media, big corporations, politicians, and our government.”

Much better as a pathway back to premodern faith, he says, is the Eastern Orthodox Church. The Orthodox, after all, can claim a link to the early church in ways other Christian traditions can’t. Orthodox liturgical and spiritual practices — intense prayers, fasting and long services — may seem arcane and rigid compared with the “seeker-friendly” openness of evangelicals and the white liberal niceness of mainline Protestants. But its oddness is precisely what Dreher says modern people need to get out of their heads and into the flow of the Divine Life.

As receipts, Dreher tells the story of being healed of chronic Epstein-Barr in 2012, after a priest told him to pray the Jesus Prayer — “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on me, a sinner” — 500 times a day. Dreher notes that the incense, chants and bowing that take place in Orthodox services helpfully engage the body as much as the mind and spirit. “We are not going to argue ourselves back to enchantment, nor are we going to behave ourselves into true goodness,” writes Dreher. “Above all, we need beauty.”

Dreher writes movingly about his own spiritual awakening as a teenager visiting Chartes Cathedral in France, and later in watching the films of Andrei Tarkovsky and reading “The Divine Comedy.” Despite his warnings against psychedelics, he also writes about a positive experience taking LSD in college.

But as “Living in Wonder” builds toward a conclusion, it increasingly reads less like a case for re-enchantment with the world and more for readers to join the Orthodox Church, and in this it betrays a naivete that dogs much of Dreher’s advocacy for a purer faith and purer religious institutions.

It’s naive to think of Eastern Orthodoxy as escaping the trappings of modernity, as if the other Christian traditions passed through the Enlightenment while the Orthodox somehow stayed ensconced in 650 A.D. Orthodoxy’s growing popularity among young American men, largely due to videos and podcasts on the internet, is a peculiarly modern phenomenon, and not only because digital culture itself is modern.

As Dreher has noted, Orthodox leaders have been readily conscripted into wars both literal and cultural, showing that the church is as susceptible to modern upheaval and institutional scandal as any other religious body. Sarah Riccardi-Swartz has written about the small but vocal far-right group of converts who treat Orthodoxy as a kind of Christianity on steroids that rejects modernist rationalism but is still rigorous enough for manly men. (She also spoke about this on “Saved by the City,” the RNS podcast I co-host).

In their hands, Orthodoxy easily becomes a tool in the quest to bolster Western civilization — making traditional Christianity a means to a worldly end, rather than a pathway of humble devotion and awe before a transcendent God.

Charles Taylor predicted that moderns would seek enchantment by retreating back, rather than stretching forward. “Many people are not satisfied with a momentary sense of wow!” he writes. “They want to take it further, and they’re looking for ways of doing so. That is what leads them into the practices which are the main access to traditional forms of faith.”

In other words, many people need a container for their experiences of awe. They seek a tradition or community that orders their spiritual impulses and holds them accountable to what people in the past have said and taught about God.

But no tradition or community stands outside of time. There is no going back to premodern life, however much we romanticize a past where spiritual beings were ever-present, where no one thought to doubt the existence of God, where the physical and spiritual life were of a whole. Every religious tradition stands within culture, not outside of it. They are made of people, bound by space and time. The only way to enchantment is through, not around, the spiritual challenges of modern life.

(Katelyn Beaty, editorial director of Brazos Press, is the author of “Celebrities for Jesus” and co-host of the RNS podcast “Saved by the City.” She blogs at The Beaty Beat. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)