(RNS) — In mid-February, Southern Baptist Convention leaders received grim news. The denomination’s Executive Committee was essentially broke.

Over the past four years, the committee has spent more than $13 million on legal fees and other costs related to a historic sexual abuse investigation by Guidepost Solutions, draining its reserves and leaving it unable to pay its bills for the following year. Among those bills were $3 million in additional legal fees for the upcoming year, with more likely to come.

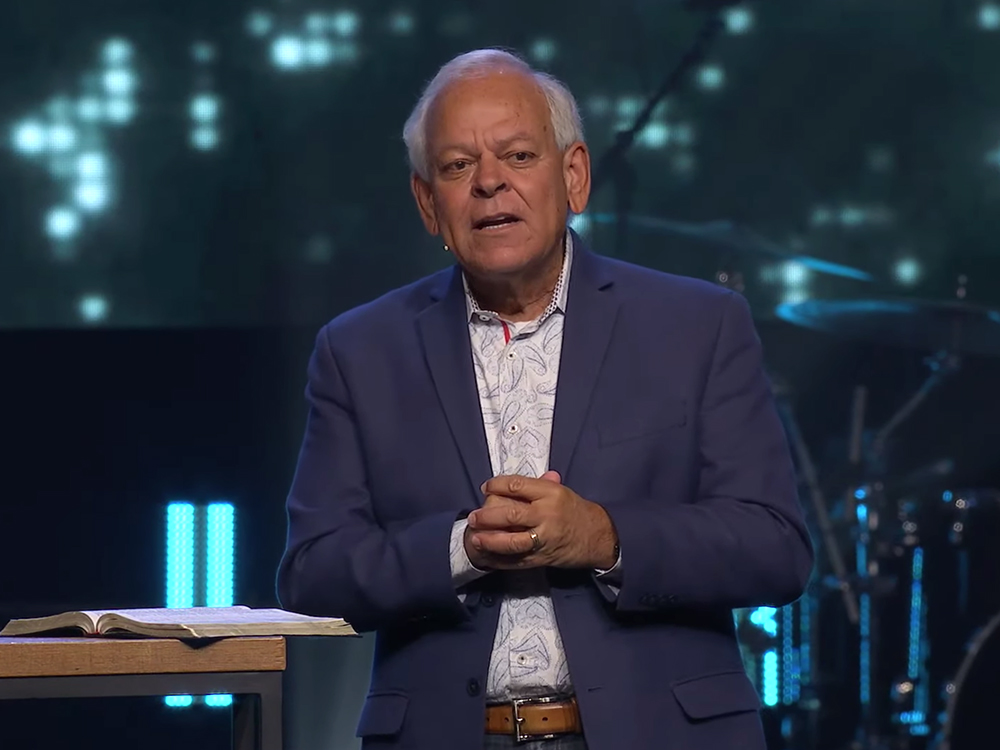

“Those bills are due,” Jeff Iorg, president of the SBC Executive Committee, said in his speech to SBC leaders meeting at a Nashville, Tennessee, airport hotel in February. “And they must be paid.”

To deal with the financial crisis, the Executive Committee has put its Nashville headquarters up for sale, cut staff and applied for a $3 million loan. The committee is also seeking a $3 million “priority allocation” for legal fees from the denomination’s $190 million Cooperative Program budget, which is usually used for missions and ministries.

Iorg said the committee had avoided tapping those funds for years. Now, there are no other options.

“This is a controversial and difficult recommendation to make,” Iorg said. “No mission-centered Southern Baptist wants to take this action. I don’t, you don’t. No one does. But we have exhausted other definitive options.”

Jeff Iorg, president of the Southern Baptist Convention Executive Committee, speaks during the committee’s annual meeting on Feb. 18, 2025, in Nashville, Tenn. (RNS photo/Bob Smietana)

The SBC budget, including the legal allocation, must be approved during the denomination’s annual meeting in June. It’s unclear what will happen if the request fails.

How did the nation’s largest Protestant denomination get in such financial trouble?

One reason is Johnny Hunt.

Hunt, a former Southern Baptist Convention president and megachurch pastor, sued the denomination in 2023, after allegations he had sexually assaulted another pastor’s wife were published in the Guidepost report. Hunt denied the allegations at first, then said the sexual conduct was consensual.

His lawyers have argued Hunt’s sins were nobody’s business but God’s and have sought tens of millions of dollars in damages.

As of fall 2024, the Executive Committee had spent more than $3.1 million on legal fees related to the Hunt lawsuit and a second suit filed by David Sills, a former seminary professor named in the report. Most of the costs were due to the Hunt lawsuit, which goes to trial in June.

The costs from Hunt’s lawsuit have also essentially doubled because the Executive Committee agreed to pay Guidepost’s legal fees in any lawsuit based on its investigation, a process known as indemnification.

Pastor Johnny Hunt speaks in 2020. (Video screen grab)

Hunt also played a key role in the Great Commission Resurgence, a 2010 initiative that cut the Executive Committee’s funding to give more money to missions.

Hunt’s attorneys did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Executive Committee leaders also spent $2 million on the Guidepost investigation and another $2 million on an ongoing investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.

The longer answer to the fiscal woes is that the SBC is an inherently fragile organization. Though it boasts about 13 million members and more than 46,000 churches — which collect about $10 billion a year, most of which stays within those churches — the overarching SBC organization is held together by a volunteer committee, a tiny staff and a relatively minuscule budget.

In essence, SBC is a billion-dollar organization that spends almost no money on administration or oversight on a national level. Only about 3% of SBC funding goes to the Executive Committee, which runs the SBC in between its annual meetings, collects donations and handles the denomination’s legal affairs.

A combination of inflation, legal fees and the rising cost of putting on the growing annual meeting has strained the Executive Committee’s budget. In 2014, the meeting drew about 5,200 messengers, and last year’s drew nearly 11,000.

Most of the money donated to the SBC’s Cooperative Program — which funds theological education and mission work — goes to the SBC’s six seminaries and two major mission boards. Those entities hold hundreds of millions in reserves.

Messengers attend the first day of the Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in New Orleans on June 13, 2023. (RNS photo/Emily Kask)

When Southern Baptists approved the Guidepost investigation, they also approved the idea of using Cooperative Program funds for dealing with abuse. However, the messengers did not approve an official budget for the investigation, and attempts to tap those funds stalled in 2021.

Iorg said there’s no way of knowing what future legal costs might be. However, he told SBC leaders he hopes the $3 million allocation and the eventual sale of the Executive Committee building will alleviate most of the current budget woes.

Marshall Blalock, pastor of First Baptist Church in Charleston, South Carolina, said the Executive Committee is in an “unenviable situation.” SBC leaders followed the will of the messengers, he said, and that came with a cost.

He backed the idea of a priority allocation to fund legal bills.

“They have to pay these expenses,” said Blalock, who served on the committee that oversaw the Guidepost investigation. “When the money runs out, it has to come from somewhere.”

Pastor Marshall Blalock, chair of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Abuse Reform Implementation Task Force, speaks during the annual meeting in New Orleans, June 14, 2023. (RNS photo/Emily Kask)

Blalock said he’s heard critics blame the task force or past Executive Committees for the current budget shortfall. That’s misguided, he said.

“They are blaming the wrong people,” he said.

The budget shortfall, he said, was caused mainly by lawsuits from those named in the Guidepost report, and that’s where the blame should lie.

“The ideal solution would be for people to stop suing us,” he said, while not naming specific names.

Blalock also said he worries the lawsuits have slowed abuse reforms in the SBC, such as a proposed database that would name abusive pastors. Defending against lawsuits has dried up funds that could have been used for reforms — and made Baptist leaders wary of reforms, such as a database.

The Guidepost investigation was delayed in 2021 for weeks due to a heated debate over waiving attorney-client privilege — essentially giving investigators access to correspondence between SBC leaders and their lawyers. After a number of resignations, the committee waived privilege.

Some critics of waiving privilege claimed at the time that waiving privilege would lead to financial ruin for the SBC. Supporters of those critics now claim they were right. A spokesman for the Executive Committee said it was difficult to determine what one factor caused the rise in legal fees.

“The waiving of privilege was one of many critical decisions that have impacted the finances of the SBC Executive Committee,” Brandon Porter, the Executive Committee’s vice president for communications, said in an email. “While not individually quantifiable, those combined decisions have led to substantial and continued costs.”

Tapping Cooperative Program funds could come with some unintended consequences. During the Executive Committee’s meeting in February, Dani Bryson, a committee member from Tennessee, said doing so could jeopardize funds the SBC has long sought to protect in the event it ever loses a lawsuit.

“If we’re going to be standing before a court trying to tell them that we don’t have access to all the Cooperative Program funds, this designation sure doesn’t make that look true,” she said during the meeting.

In an interview, Bryson said that if the proposal to tap Cooperative Program funds fails this summer, the committee will have to come up with a different approach.

Bruce Frank, the North Carolina megachurch pastor who chaired the abuse task force that oversaw the Guidepost investigation, said he’d back the plan to tap Cooperative Program funds and that paying the SBC’s legal bills is part of the cost of running a major denomination.

“We can’t talk about how large of an organization we are and how we’re the largest Protestant denomination, and then say we can’t afford the basic cost of running this,” he said.