(RNS) — Is yoga Indic physiotherapy, a wellness routine, spiritual practice or something else entirely?

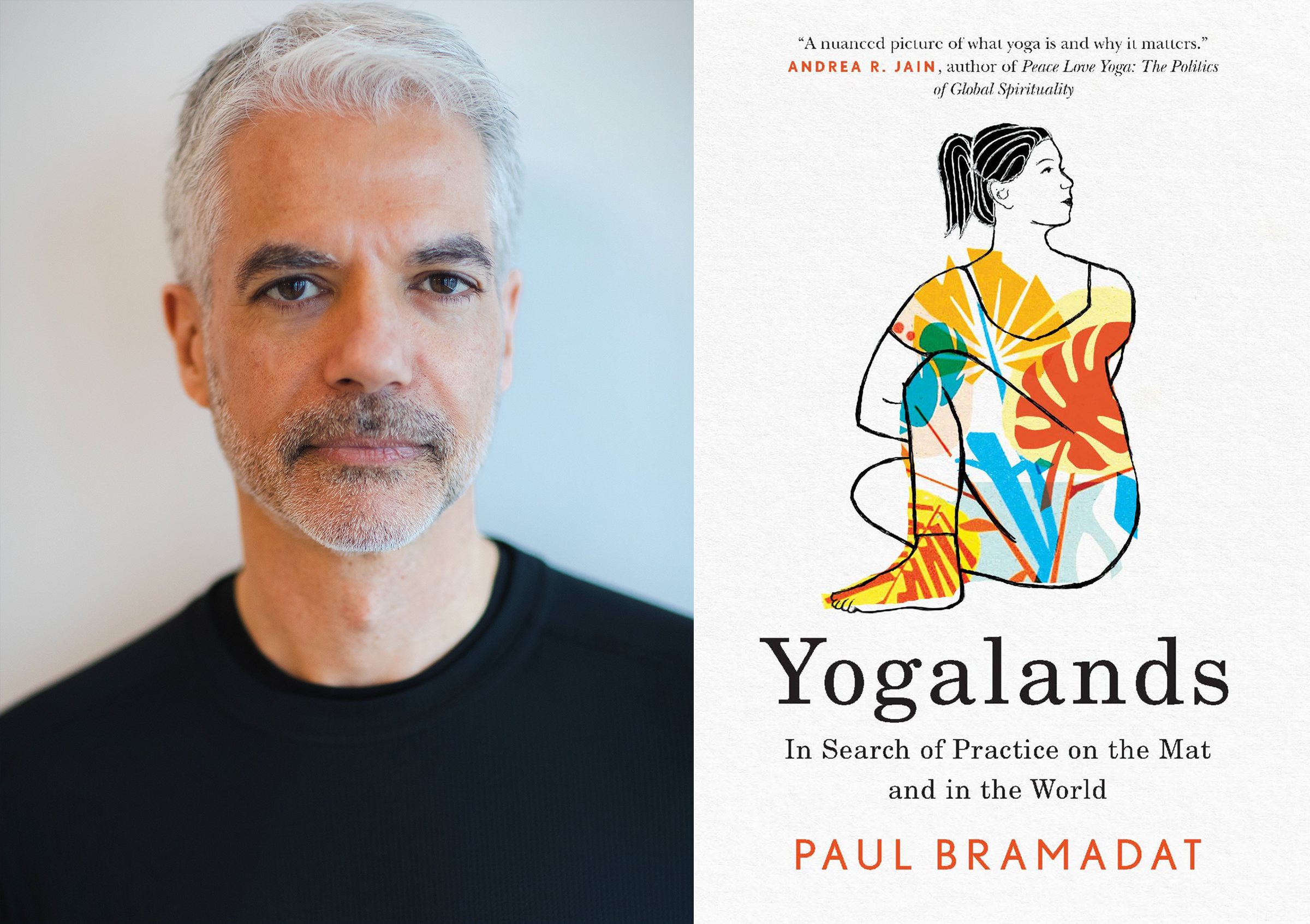

Canadian religion scholar Paul Bramadat dives headstand first into that question as he analyzes the complex, evolving world of modern postural yoga in his forthcoming book, “Yogalands: In Search of Practice on the Mat and in the World.”

Straddling the sacred and the secular, Bramadat, a longtime Ashtanga yoga practitioner, draws from his own experience and interviews with teachers and students across North America to explore how yoga is political. The book, which will be released on April 8, explores yoga’s intersections with commodification, cultural appropriation, power hierarchies and sexual misconduct.

As yoga classes maintain popularity among the “spiritual, but not religious” crowd, Bramadat challenges readers to consider both yoga’s ancient roots and its modern societal impact. And, the half Indo-Trinidadian sociologist of religion asks, “Why are 80% of yoga practitioners in North America white women?”

His interview with RNS has been edited for length and clarity.

Was Ashtanga yoga at age 45 really your first experience?

Isn’t that strange? It’s like having your first experience of Christianity be a Russian Orthodox Church.

I entered the community largely in crisis and in panic because my knees were in such dire shape, and I was just willing to do anything. A colleague assured me this style of yoga would be very minimally woo woo, and I wouldn’t feel like I was working because, of course, I think about religion and spirituality all day, every day. That’s my job. He said, this will be much more about the stretching and the strengthening and the reorganization of your body. And you know, he meant well.

Paul Bramadat, standing, is director of the Centre for Studies in Religion and Society at the University of Victoria. (Photo by Xavier Walker)

You describe yourself as a skeptical scholar but a devoted practitioner. Which of your questions about yoga were you most interested in answering?

What I was most curious about was, what were all these white folks doing in this Indic practice? How was yoga as a philosophy and a set of postures landing in their lives? Then it became impossible for me to not think about how it might land in my life, and whether or not it might actually be kind of a path forward for me.

Yoga was made by men, for men, about men: It just imagines the male body for the vast majority of Indian history. And yet, you see its popularity in North America being principally among white people and mostly among women. It’s very fascinating to me how this massive, complex tradition could shift its orientation and its audience in the space of some decades.

How have practitioners and advocates tried to either keep yoga’s Hindu religious elements or move away from them?

Within what we might call the lineage traditions, like Ashtanga or Iyengar, there’s a real effort to maintain the guru-shishya (teacher-student) style of teaching, and in maintaining some connection to ashrams or training sites in India and Sanskrit concepts and chants and artistic styles.

At the same time, there’s a very clear awareness from teachers, both in lineage traditions and outside of them, that if you make this space and practice too religion-like, people will balk. So there’s that weird tension between really wanting to maintain the links to India and to the lineage-based traditions, and then the sense that if the link is too thick, people will flee.

It’s always sad to me when teachers don’t take the opportunity to say to people, “These traditions are complex and beautiful, and you could actually use them as windows onto these other ways of being and other ways of knowing.” For me, a more interesting form of yoga helps you manage your body, your trauma and your suffering, but also says, “These techniques, these ideas, these postures are related to a worldview, or worldviews, that have something to contribute to your sense of the good life and truth and beauty.”

I don’t really support the idea that yoga has to be only Indic. I think it’s a set of ideas and practices that can be useful for lots of people. I think it’s useful to know the historical, philosophical background of the tradition, but I don’t think any particular ethno-religious or ethno-racial culture has a lock on it.

It struck me that cultural appropriation seemed like a nonissue in some people’s minds. Do you find that to be widespread and true?

I expected cultural appropriation to be something that everyone was going to want to talk about. But almost every time I would bring it up, it would sort of fall flat. Many of them felt like they had made peace with that question, or are adequately respectful of the Indian religion and roots of yoga, or had spent months or years in India studying with their guru.

And when I would bring up the question of, “Is it strange that your classes are mostly white women?” they would say, “Yes, that might seem strange from the outside, but everybody’s suffering in their own ways.” So, again, it was a real surprise to me that it didn’t seem to be a very live dilemma for people.

Where does what you call “therapeutic individualism” fall into the conversation, especially for an increasingly secular population?

Most people are not practicing yoga in North America for capital R religious reasons. They’re practicing elements of yoga to manage their suffering, frankly. So I think therapeutic individualism is an approach to the self, where the individual’s duty is to help themselves achieve some sense of well-being in their bodies. And I think postural yoga does a very, very good job of that, and so it fits perfectly within the cultural context that really supports therapeutic individualism.

People don’t feel any longer that they need to belong to a capital I institution or capital R religion in order to be well. Pretty clearly, yoga is delivering some sense of wholeness to people who often feel they’re frazzled by or traumatized by the culture in which they live. This was such a large movement, it made sense to me as a response to growing trends of secularization in our culture.

“Yogalands: In Search of Practice on the Mat and in the World” by Paul Bramadat. (Courtesy image)

Can you explain how yoga in North America is political?

I’m interested in how the popularity of yoga might be seen as a kind of a small p political pushback against something that’s problematic in the status quo in North America. I talk about how there was a consensus that the world is too “loud, fast and dirty,” and the yoga space is political in that it gives people an opportunity to be “quiet, slow and clean.” This is a kind of an indictment of the way the world is — too kind of tilted toward neoliberalism, where the individual is left on their own, and that state is not really a safe space for the individual to thrive.

The idea that religion and perhaps yoga are kind of opiates of the masses is a very common critique. There’s something to be said for that critique, except if that calming meditation allows you to actually survive and go out into the world and try to be a more effective mother or soccer player or accountant or dentist, then that, for me, seems to be not a terrible thing.

You talk about how the guru-shishya model has lent itself to sexual misconduct scandals. What did you take away from your exploration into these issues?

I think we see these sexual misconduct scandals pretty much across the yoga spectrum, and certainly when there’s a strong guru-shishya model, where the teacher has tremendous power. It’s when the teacher is seen as a special figure, almost ontologically different, that creates all kinds of potential for terrible misconduct.

In the wake of #MeToo and all the scandals in the yoga scene, they’ve gotten much better at catching monsters or identifying egregious harms. I think we see this in the consent cards that are now more and more popular on yoga studio websites and in teacher training programs. I think the postural yoga communities in North America have gotten better at recognizing and coming to terms with it.

Can you talk about the “superhuman” yoga influencers who have made yoga in North America what it is today?

If you google yoga studios, you can tell immediately there are stars in the studios. Sometimes, the stars are the teachers. Sometimes the stars are particular students who seem to be able to do anything with their bodies, and they seem to be able to do it without trying very hard.

I think it’s difficult to think about the growth of postural yoga in North America without thinking of these people — just as it’s difficult to think about how Christianity spread without thinking about the power of martyrs and saints. These were also remarkable people who had all kinds of gifts.

In the yoga context, they are kind of super-people. They’re absolutely crucial to the power of postural yoga communities because they give ordinary practitioners like me the sense of what the body has the capacity to be like, to look like and to move like.