(RNS) — Muslims in North America are celebrating Eid Al-Fitr, marking the end of the holy month of Ramadan. Around the world, people celebrate by donning their best attire, gathering for prayers and exchanging gifts.

For incarcerated Muslims, though, the holiday looks drastically different. While some can celebrate with other Muslims in their facility, many observe the holiday in isolation.

Earlier this month, Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims, an Ohio grassroots project that for the past five years has facilitated an annual Eid Al-Fitr letter-writing campaign for incarcerated Muslims in the state, hosted a webinar about its efforts.

The project aims to connect with incarcerated Muslims and sees advocacy for prison abolishment as an important part of practicing the Islamic faith, according to the group. To volunteers and leaders, letter writing is a form of advocacy work foundational to their spiritual and political commitments.

One of ELIM’s core organizers, Mariam Khan, sees the group’s work as a form of worship that follows in the example of the Prophet Muhammad.

“When I read about the Sunnah (the Prophet Muhammad’s recorded practices) and life of the Prophet, I see him as a community organizer, someone giving the clothes off his back and the money in his pocket to the most needy,” Khan said. “I want to create an Islamic practice that centers around action, around material change through our faith. That extends to our incarcerated brothers and sisters.”

This year, ELIM volunteers gathered nearly 350 letters through community partnerships and writing events, like the annual webinar. The letters are being distributed to 230 men in two Ohio facilities: Lebanon Correctional Institution and the Ohio State Penitentiary. The recipients were identified through a “fasting roll call,” or a list of people who requested fasting accommodations provided to ELIM by facilities’ chaplains and other intermediaries.

ELIM is one of several faith-based groups across the country reaching those inside prisons through letter writing and resource distribution. Volunteer-run groups like the Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund, Sacramento Letters to Incarcerated Muslims and nonprofits like Believers Bail Out share a similar mission, also ultimately seeking prison abolishment. They run independently and focus on their respective locales.

Zumana Noor, a core leader for the Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund, said the group’s work is rooted in solidarity, not charity.

“It’s our duty as Muslims to support our brothers and sisters in need, including those behind bars,” Noor said. “That’s really the center of what we do. It’s about compassion, about giving back.”

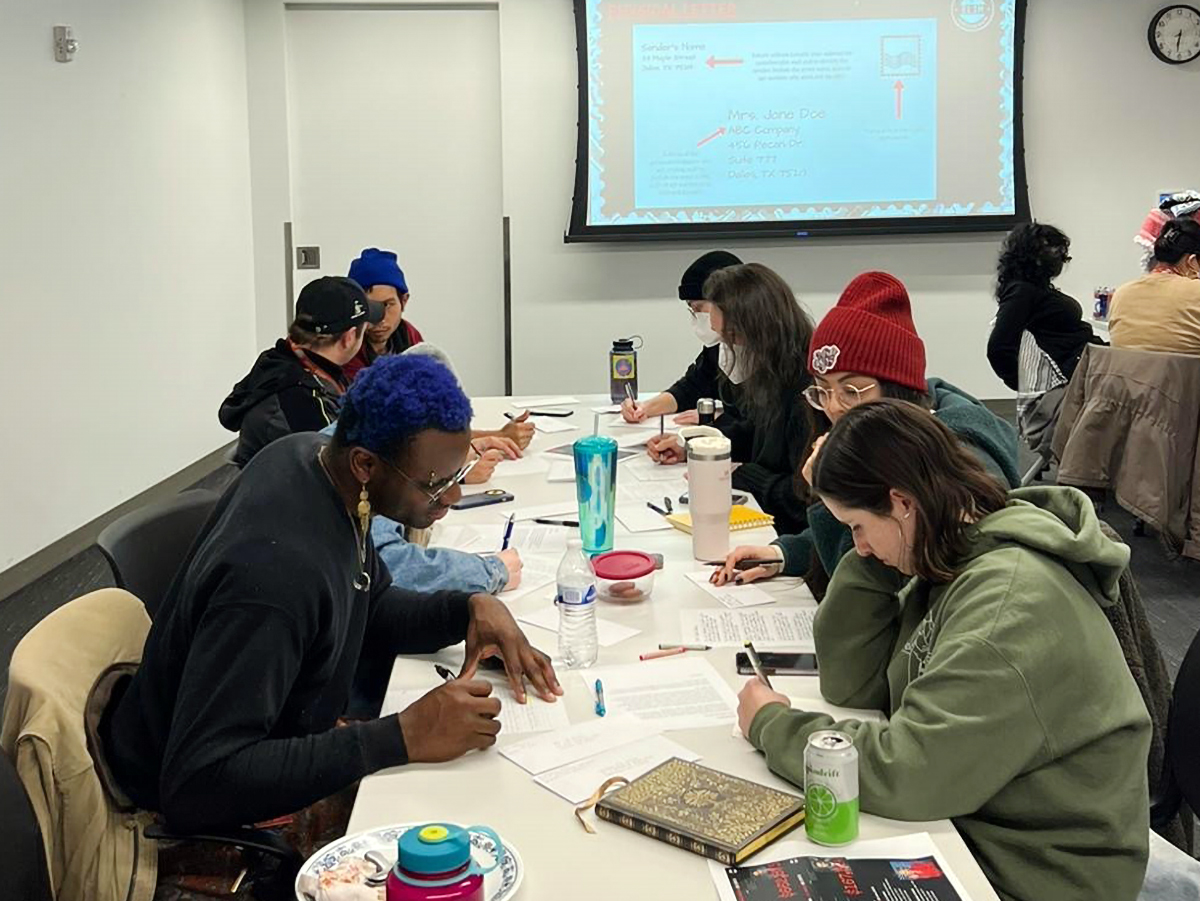

A Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund letter-writing event on June 20, 2024. (Photo courtesy PMFF)

Noor also noted the often intangible impact of such outreach.

“When the system sees that someone is being cared for, that there are people checking in and mailing letters, they’re less likely to pull stuff with them,” Noor said. “They know there are people on the outside who will speak up.”

Kenza Kamal, one of ELIM’s founding members, emphasized that incarcerated Muslims have much to offer.

“The folks inside are highly learned,” Kamal said. “They study and know things that many of us on the outside have not had the focus, discipline or the pressure to learn.”

For ELIM organizers, letter writing is a way to connect with incarcerated people and send a message of hope for the future, with ending incarceration being the ultimate goal.

“Abolition isn’t separate from Islam,” said Ridha Nazir, a newer ELIM organizer. “It teaches us to stand with the oppressed and to never lose sight of justice and to act with mercy. When we write these letters for incarcerated Muslims, we’re doing more than just sending words on a page. We’re extending solidarity, we’re extending care, we’re extending the spiritual connection.”

Moreover, Nazir said, the prison system “is designed to isolate, and disappear people,” to which Islam stands in contrast.

“For us, letter writing is an act of worship,” Nazir said.

However, the Ohio campaign has at least one new obstacle. A new policy from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, effective Feb. 1, mandates all incoming letters be copied or scanned into an electronic format for delivery and the originals destroyed after 30 days. Inmates can no longer receive original — often handwritten — letters from ELIM.

Fardowsa Dahir, another ELIM organizer, said new restrictions seem to be implemented every year in the state. And, much communication getting into the facilities relies on one person, like an amenable imam or chaplain, Khan added.

“When that person stops communicating with us, that’s the end of our lifeline to administer and organize this project,” Khan said.

The new mail policy also affects the emotional weight of the letters, Nazir said, as the scanning process strips away some of the personal and spiritual intimacy that handwritten letters offer.

“We always want to work in the way of the Prophet (Muhammad), and we’re following the example he set,” Nazir said. “He never turned his back on those who are isolated or imprisoned or struggling. And so, we remember the Quranic verses that tell us to speak truth, to show up and to not be complicit to injustice through silence.”

This article was produced as part of the RNS/Interfaith America Religion Journalism Fellowship.