(RNS) — Several years ago, theology professor Mike Tapper asked a group of young, aspiring pastors how many had ever been to a funeral.

Less than half, it turned out. Many had never been in the same room as a dead person.

Tapper, who teaches in the school of theology and ministry at Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion, worried what might happen when his students found themselves ministering at a church.

“I don’t want their first officiated funeral to essentially be their first funeral experience,” he said.

That’s why Tapper and some of his students began taking trips to the school’s cadaver lab. The idea was to get them used to being around someone who had died. The students first visited the lab in March during Lent, the time of the church year when Christians prepare for remembering the death and resurrection of Jesus during Holy Week.

They then performed a mock funeral for the cadavers they met in the lab. It took some getting used to.

Joshua Martin, a third-year student in Tapper’s Theology and Practice of Christian Worship class, said he’d been to a funeral before, so he did not think going to the cadaver lab would be a big deal. Then, he started to worry a bit.

“I thought, this is going to be serious,” he said.

Caden Mack, also a third-year student, said he “definitely did not see it coming when I signed up for the class,” but the visits to the cadaver lab sounded like a good idea.

Not everyone in the class was thrilled with Tapper’s plan. Naomi Rugh, a third-year student, said she cried in class the first time she heard about the upcoming trip to the cadaver lab. In the days leading up to the first visit, Rugh said she spent a lot of time asking herself what God wanted her to learn from the experience and how might it prepare her for a future in ministry. She also thought of Jesus, recalling the Bible said he became acquainted with death for the sake of his followers.

“What am I going to learn from this for other people?” Rugh asked herself.

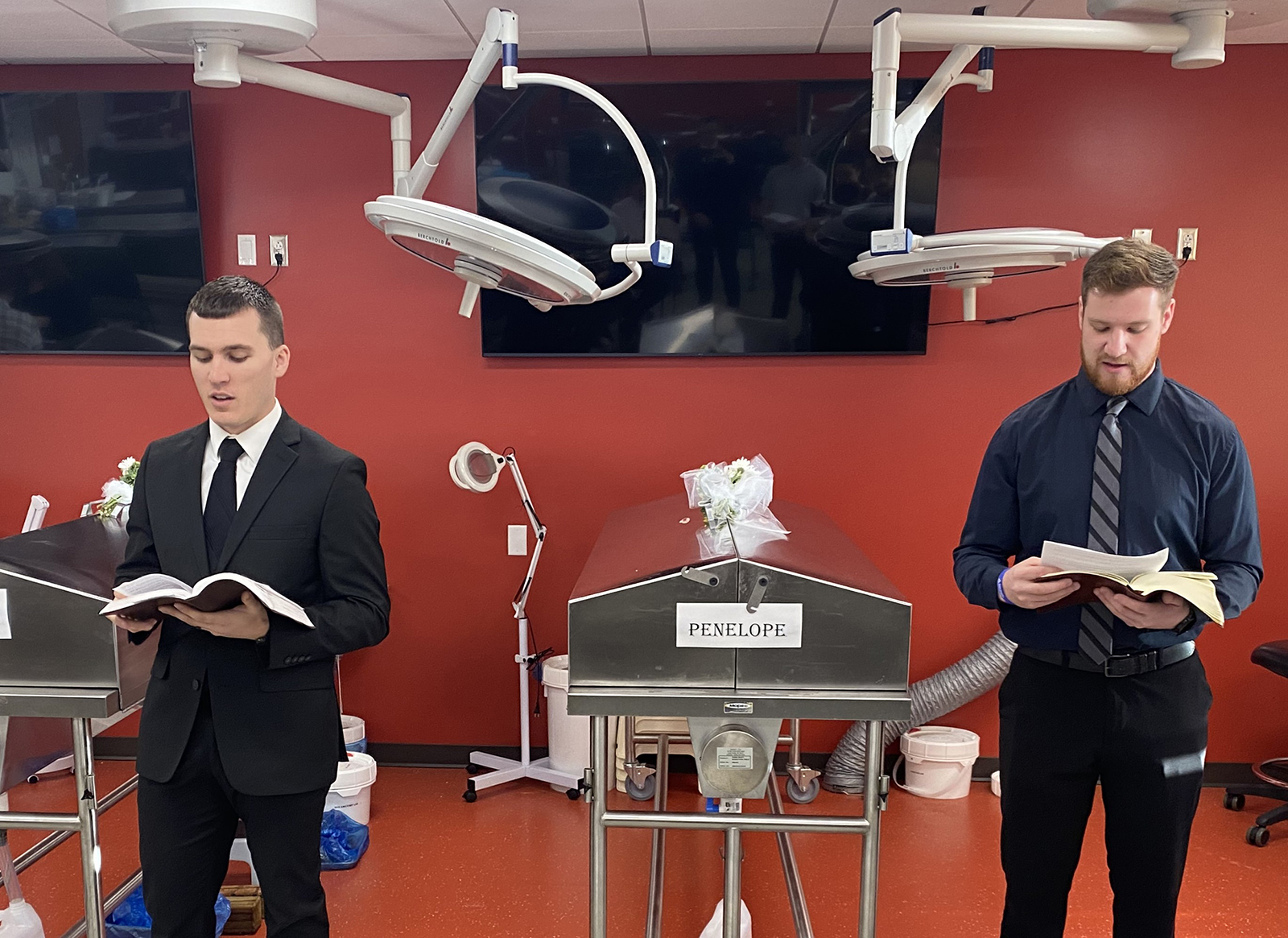

Joshua Martin during a mock funeral service at Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion, Indiana, in March 2025. (Photo courtesy Indiana Wesleyan University)

Britt Storms, an associate professor and anatomist who teaches in the physical and occupational therapy programs at Indiana Wesleyan, oversees the school’s cadaver lab. While the cadavers — whom Storms refers to as “friends” — were donated to use for learning, not every student needs to encounter them, she told RNS.

“I’m not going to bring an accounting student in just to see the bodies,” Storms said.

When Storms’ dean approached her about working with Tapper, she thought it was a good idea. But she had some concerns, mainly whether students were properly prepared for the experience. Medical cadavers, she said, “don’t look like us anymore,” which can be a shock.

Storms said she also has very clear rules about cadavers being treated with respect. There’s no photography or videography allowed while students are working with them. She collects phones from students when they enter the lab and tolerates no nonsense, she said.

“I put the fear of God in them,” she said.

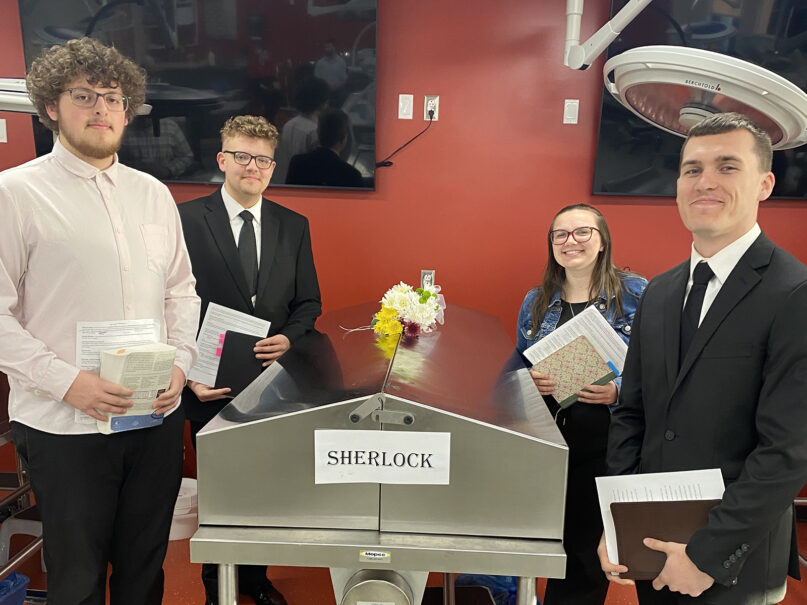

Storms also gives every cadaver a new name to remind students to show respect for the person who donated their body. “That’s not Table No. 7,” she said, “that’s Sherlock.”

Martin said when he first entered the lab, Bernadette, one of the cadavers, was face down, so he didn’t feel much of a connection. He thought, “This is what we look like when we die.”

Ian Milbourn, from left, Christopher Paterson, Zoe Stroud and Chad Harbert at Indiana Wesleyan University in Marion, Indiana, in March 2025. (Photo courtesy Indiana Wesleyan University)

But when the cadaver was turned over, that changed.

“I started thinking, this was a person with a story,” Martin said. “This was somebody who had a life, and there’s something beautiful to the fact that they’re continuing to teach people past the point where they were alive.”

During the students’ first visit to the lab, the hoods on the cadaver tables were open so the students could experience what it was like to be in their presence. On the second visit, the hoods were closed — much like a casket at a funeral service — and their assignment was to perform parts of a funeral service, including a welcome, Bible readings, a eulogy and graveside prayers.

Rather than read from a script, each student planned out the services and wrote a brief eulogy, for which students were given a brief synopsis of the donor’s life to draw from. For example, one of the people who donated their body was a grandfather who loved to fish and to spend time with his family.

“These students are much better prepared today than they were even a few weeks ago to actually officiate funerals early in their ministry,” said Tapper, who hopes to continue the cadaver lab visits for his students.

Naomi Rugh places flowers during mock funeral services at Indiana Wesleyan University in March 2025. (Photo courtesy Indiana Wesleyan University)

Zoe Stroud, a third-year student, agreed.

“It was a sacred event that we wanted to be worshipful,” she said. “I came out feeling way more prepared to give a funeral than I went in.”

For at least one student, taking part in the mock funeral became overwhelming. Bi Khaimi was assigned to give a eulogy for a cadaver named Penelope, and as he began to write her story, he also began to grieve. He became overwhelmed with sorrow while doing the class funeral and could not go on.

“I could not bring myself to go to the last bit of it because it became too personal,” Khaimi said.

Still, he said the experience was good for him and that he’d feel better prepared if called on to officiate a funeral, knowing the emotions he might have to deal with.

Rugh said Tapper gave students the option of doing an alternative assignment instead of visiting the cadaver lab, which she considered. She eventually decided to go, though, in part because it would help her better prepare for Easter and understand what Jesus went through in the crucifixion.

“God went through that so that we could be redeemed,” she said.