(RNS) — At the funeral of Pope Francis, one image stood out: Donald Trump, wearing a blue suit in a sea of black, seemingly restless and detached from the solemn liturgy unfolding around him. Already Trump had upstaged the late pontiff by publicly meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as the service was starting, turning a moment of spiritual mourning into a stage for political theater.

These scenes captured something essential about the uneasy relationship between political power and Christianity in our time.

Trump’s engagement with Christianity has consistently been pragmatic rather than devotional. This relationship was seen again on Thursday (May 1), when, in the company of key representatives of his religious-political base, he established a religious liberty commission by promising to rid the country of “anti-Christian bias.”

Trump has embraced Christian symbolism in his use of the Bible, cultivated the support of religious leaders and invoked faith at political rallies. But at each new turn it’s clear that Christianity is not something to be inhabited or challenged by, but a tool to be used.

Trump is hardly the first leader to recognize Christianity’s political potential.

Seventeen centuries ago, Constantine, emperor of the Roman Empire, faced a fracturing religious landscape. Christianity, though still emerging from centuries of persecution, offered something rare: A movement capable of unifying diverse peoples around a common identity. Constantine’s so-called “conversion” — long debated because of its syncretistic blend of genuine religious experience with shrewd political calculation — reshaped the trajectory of both the Church and the Empire.

This complexity is emphasized in two recent studies on Constantine: David Potter’s “Constantine the Emperor” and Christopher P. Jones’ “Between Pagan and Christian.”

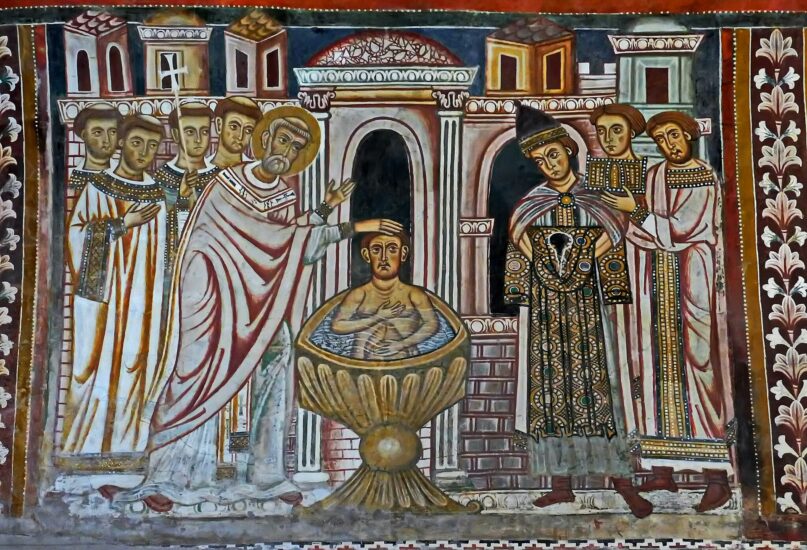

A mosaic of St. Silvester baptizing Emperor Constantine, from the Basilica Santi Quattro Coronati in Rome. (Photo by Peter1936F/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA)

Potter, a historian at the University of Michigan, notes that through Constantine, “Christianity (became) associated with the very substance that holds the empire together: the ideology of imperial victory.” Jones, a scholar of late antiquity at Harvard University, puts it as bluntly: for Constantine, the Christian God became “a god strong to aid,” uniting empire and faith under a single divine authority and offering Constantine a new source of legitimacy and imperial control.

But the Christianity that emerged under Constantine was not the same faith that had survived through centuries of martyrdom.

Before Constantine, Christian communities were diverse, decentralized and often theologically fragmented. Early Christians argued — sometimes fiercely — over the nature of Christ, the meaning of salvation and the authority of Scripture. Heresy, in this period, was a communal and pastoral concern: a wound in the body of Christ, not a crime against the state.

After Constantine, much of this began to change.

In 325 C.E., 1,700 years ago this May, the emperor convened the Council of Nicaea, summoning bishops from across the empire, many of them local pastors with little formal theological education, to forge a unified statement of faith. The council’s goal was not merely theological clarity. It was imperial stability.

For the first time, Christian belief was not only about faithfulness to Christ; it became a matter of loyalty to the emperor. Heresy was no longer just a spiritual wound in the body of Christ — it became a political threat to imperial order. Christianity was disciplined into a form more useful for holding an empire together.

Today, a similar phenomenon is unfolding.

President Donald Trump, surrounded by religious leaders, listens to a musical performance before signing an executive order during a National Day of Prayer event in the Rose Garden of the White House, Thursday, May 1, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Trump has not called a council or penned a creed — he hardly needs to. Yet he has elevated a particular expression of Christianity — nationalist, triumphalist, often exclusionary — that serves his political interests.

The Christianity most visibly aligned with Trumpism is one that emphasizes strength, victory and cultural dominance. It is a Christianity that views theological complexity with suspicion and prophetic dissent as disloyalty, and it replaces the messy, demanding ethics of the Sermon on the Mount with a simpler narrative of winning and losing.

Just as Constantine’s Christianity sidelined alternative voices in the early church, so, too, today a broader, more diverse Christian witness is being marginalized. Christians who emphasize racial justice, immigration reform, care for the marginalized or global solidarity find themselves portrayed as political adversaries rather than fellow believers. In both cases, the gospel is narrowed and made to serve the needs of empire rather than the mission of Christ.

The risk of this pattern is not only political. When Christianity becomes too closely aligned with any empire, it loses its capacity to speak prophetically. It forgets its identity as a pilgrim people, called to embody the kingdom of God, not the kingdoms of this world.

The early Christians who refused to offer incense to Caesar understood this. They were willing to be misunderstood, marginalized, even martyred rather than allow their faith to be co-opted by imperial power.

In our time, the temptation is subtler but no less dangerous. If Christianity in America becomes simply another tool of political mobilization, it will hollow itself out from within. It will trade the scandal of the cross — the foolishness of love, mercy, humility and sacrifice — for the false security of political dominance.

Constantine’s legacy is complex. Without him, Christianity might never have survived to become the global faith it is today. But the cost of that survival was real: a faith reshaped to serve the needs of empire.

Christians today must ask again: Will we follow a Christ who reigns from a cross or one who crowns emperors to secure his own power?

(The Very Rev. Michael W. DeLashmutt is senior vice president and dean of the chapel at the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York City and author of the forthcoming “A Lived Theology of Everyday Life.” His Substack is “Making Theology.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)