PHILADELPHIA (RNS) — The assignment for Keziah Ridgeway’s class at Northeast High School in December 2023 didn’t mention Israel or Palestinians. After discussing Black spirituals in a section on American slavery, Ridgeway’s AP African American history students were asked to present examples of artistic expression from oppressed groups.

Two sophomore boys produced a single-episode podcast comparing spirituals to the work of Palestinian artist Emily Jacir and murals painted on the separation wall in the West Bank. “The Palestinian struggle is complex and art has became (sic) a vital tool for expressing resistance,” the podcasters said, going on to explore how Palestinian folk dances and embroidery counteract the “erasure of the Palestinian narrative.”

“Art,” they concluded, “transcends time and space, connecting us to a shared human experience of overcoming adversity through creativity.”

Ridgeway, impressed with their work, got permission from her principal, Omar Crowder, to play the podcast at the school’s Black History Month assembly. After the first assembly — four were held due to the school’s size — a teacher named Lisa Appel shared photos of the student presentation on the Facebook page of a newly created group called the School District of Philadelphia Jewish Family Association.

Appel and Family Association members emailed Crowder and district officials, demanding that the presentation be pulled from the remaining assemblies. “Even if no one said the word ‘Jewish,'” they wrote, the parallels made between African American and Palestinian resistance portrayed Jewish people as the oppressors. “The narrative,” they concluded, “is antisemitic and dangerous.” Crowder conceded, and the remaining presentations were canceled.

On the day of the final assembly, leaders of the Black Student Association — Northeast, the largest high school in the Philadelphia system, is 82% students of color — came onstage holding posters protesting the ban. A student told the assembly how “white teachers in the audience” had claimed the podcast made them uncomfortable and, working with an outside organization, had convinced the district to ban the presentation.

“They want the most diverse public high school in Philadelphia to stay quiet about their decision in the violation of our students’ First Amendment rights,” the student said, adding in a parting shot, “Was it the quote-unquote antisemitism that made you uncomfortable, or was it the truth that made you feel guilty?”

Keziah Ridgeway. (Video screen grab)

Over the next year, until December 2024, the podcast episode would figure in a Department of Education finding that the Philadelphia school system has failed to manage antisemitic incidents at Northeast and elsewhere, and would result in Ridgeway, along with four other teachers in the district, being pulled from their classrooms. On Wednesday (May 14), the Council on American-Islamic Relations said it plans to hold a press conference Thursday with Ridgeway to announce the filing of a “federal lawsuit against the School District of Philadelphia … alleging unlawful discrimination and retaliation in violation of her civil rights.”

Since the Hamas attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, and Israel’s ensuing war on Gaza, much media attention has focused on pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses, student arrests and deportations, and the threat of federal funding cuts to universities over allegations of antisemitism. Largely unreported has been a parallel conflict taking place in K-12 schools that has pitted pro-Israel parents, students and teachers against their pro-Palestinian counterparts at local school boards across the country. At the heart of these fights is a long-standing battle over what exactly constitutes antisemitism.

Since the Hamas attack, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights has opened a record 159 investigations based on “shared ancestry.” The designation was introduced two decades ago by Kenneth Marcus, then head of the civil rights office, in an attempt to capture cases of religious bias he believed were not being addressed under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which names only race, sex and national origin.

More than half of the current Title VI cases concern public school districts. Some, such as Berkeley Unified School District in California, even have competing Title VI complaints, with Jewish groups alleging antisemitism on one side, and Muslims alleging anti-Palestinian, Arab and Muslim bias on the other. The disputes often begin as local matters, with parents bringing complaints to school administrators or school boards. But national organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League, the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, the Jewish Federations of North America, the Deborah Project and other major Jewish organizations have widened the scope and stakes of the investigations by bringing added funding and legal expertise to the fight.

Increasingly, the national organizations have sought to enforce a definition of antisemitism created by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, which says, “Manifestations might include the targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity,” adding, “criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.” Of its 11 examples of antisemitism, however, seven refer to Israel.

In 2019, President Donald Trump issued his first executive order explicitly linking Title VI cases to antisemitism and asked agencies to “consider” the IHRA definition when determining them. In 2023, Marcus, the founder of the Louis D. Brandeis Center, praised a Biden administration announcement that eight federal agencies would employ Title VI to combat antisemitism. But one step was still missing, wrote Marcus: “It’s one thing for the government to commit to addressing anti-Semitism and another for it to identify anti-Semitism properly. That is why it has always been critical that this policy be coupled with a proper, uniform definition of anti-Semitism. In our times, that definition is the IHRA Working Definition.”

After taking office again in January, Trump released a second executive order on antisemitism, asking federal departments to take all available action against antisemitism and directing the secretary of education to reexamine “all Title VI complaints and administrative actions, including in K-12 education, related to anti-Semitism — pending or resolved after October 7, 2023 with the Department’s Office of Civil Rights.”

In practice, some activists and educators say, the IHRA definition has stifled discussion about Israel and Palestinians in the classroom, inviting the targeting of teachers far beyond civil rights investigations and creating an atmosphere of fear in schools. Over the last year and a half, more than a dozen K-12 teachers across the country have been accused of antisemitism and removed from their classrooms for teaching about Palestine, posting on their personal social media accounts or supporting Palestinian, Arab or Muslim students in schools.

“The ADL and this ecosystem of organizations are relying on this conflation between any criticism of Israel, of Zionism, with antisemitism,” said anti-racism activist Nora Lester Murad, who is Jewish. “So, it becomes nearly impossible to address the real antisemitism that is taking place because that is all mixed up in this politicized and weaponized environment.”

In May 2024, a few months after the podcast assembly at Northeast, parents at Philadelphia’s top magnet school, the Masterman School, filed a Title VI complaint against the district with the help of the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia. The complaint alleged that swastikas had been drawn on a school door and students had given Nazi salutes; that on Halloween, a student dressed as a Palestinian “freedom fighter” attempted to drape a Palestinian flag over a Jewish student; and that at a bake sale to benefit victims of Sudan’s civil war, a flyer claimed Israel had “committed genocide and occupation.”

The Title VI complaint included incidents at other Philadelphia public schools, including Baldi Middle School, a feeder school for Northeast. That same month, three Baldi teachers who had displayed student posters and a Palestinian flag in the school’s lobby in November 2023 were removed from their classrooms. (A fourth teacher was also removed, for allegedly crossing out the word “Israel” on a map.) The posters had listed names and ages of children killed in Gaza along with phrases such as “Ceasefire now,” “Free Palestine,” “Antizionism is not antisemitism” and “From the river to the sea,” the latter understood by many Jews as a call to end Israel as a Jewish state but which Arab and pro-Palestinian activists believe is a call for equal rights for Palestinians.

Jordan Kardasz, one of the teachers removed from the classroom, said she and her colleagues aimed to support Palestinian, Arab and Muslim students, who were feeling increasingly alienated in their own school. “There was a clear bias in the school, a clear hatred towards Muslim and Palestinian students,” said Kardasz, who added that students told them that teachers had called them terrorists for wearing kaffiyehs. In the end, the district decided to discipline the three Baldi teachers with a five-day suspension without pay; two were to be transferred to other schools. The three teachers at Baldi resigned before the district could impose the punishment. Now, they have filed their own Title VI complaint against the district alleging discrimination against Palestinian, Arab and Muslim students.

“Both sides may be filing Title VI cases, but teachers are only being removed or reprimanded for speaking up about Palestine,” said Adam Sanchez, a former Philadelphia high school teacher who is the managing editor at Rethinking Schools, a magazine that covers social justice education. “And most of the examples that are being labeled as antisemitic are simply teachers being critical of Israel.”

A Philadelphia native and graduate of the city’s schools, Ridgeway taught Advanced Placement African American history and anthropology for International Baccalaureate students. In 2020, she won the district’s prestigious Lindback Distinguished Teacher Award. Fellow teachers described her as a popular and “excellent” teacher. Students praise her for expanding their worldview.

Ridgeway, who wears hijab, is the school’s only visibly Black Muslim teacher, and is the faculty sponsor of both the Black and the Muslim student associations.

“That was a big part of me feeling comfortable with sharing things about myself. And she inspired me,” said a Black Muslim Northeast alum who credits Ridgeway for her interest in a career in education. (She asked not to be identified because she is worried about her future.) “Being a teacher, for her, was a full-time job, a 24-hour job — like she never stopped, even when the bell rang.”

Northeast High School in Philadelphia. (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

Once a heavily Jewish corner of Philadelphia, Northeast’s catchment area has come to be predominantly Black and Latino American, with a growing immigrant population of Chinese, Arab (including Palestinian), Brazilian, Ukrainian and Russian residents. Thirty-eight percent of students are non-native English speakers, up 10% from just two years ago, with Arabic the third most common home language, after Spanish and Portuguese. Its Muslim Students Association holds weekly Juma’a, or Friday, prayers for students and staff.

The Jewish community’s legacy in Northeast is still present in its active alumni association. The Alisha C. Levin Memorial Fund, founded by a Jewish alumna’s family to commemorate the loss of their daughter on 9/11, helps fund scholarships at Northeast and science and sports programs, though last Sept. 11 the family informed the district that it planned to “reevaluate” their involvement based on the “rise of antisemitism based on issues with a teacher at Northeast High School.”

According to Northeast students, tensions at the school first began to rise just days after Israel’s retaliation on Gaza, when administrators told students they could not wear the kaffiyeh because it violated the school’s dress code.

“My sister and I got called over by a teacher who said: ‘You guys can’t wear political things. You’re not allowed to wear that,’” said Sedeen Lami, a Palestinian American senior who had taken Ridgeway’s IB anthropology class.

It felt starkly different, Lami said, from the outbreak of war in Ukraine, when both teachers and students donned Ukraine pins and wore Ukrainian colors. After meeting with school administrators, Lami and other pro-Palestinian students formed an alternative plan. They would make pins supporting Sudan and Palestine to sell as a fundraiser for relief, as students had done for Ukraine in 2022.

Lami and two Sudanese students designed three pins — one with the Palestinian flag that said “Free Palestine”; one that said “Sudan in our hearts,” remembering victims of that country’s civil war; and a third with both flags. Ridgeway, who was assisting the students, was told that, unlike the Ukraine pins, which were made at school, the pins supporting Gaza and Sudan would have to be made elsewhere. Ridgeway helped the students find a company to produce them, and the students sold 700 pins for $3 each, donating the proceeds to Palestinian and Sudanese organizations.

Ridgeway would not go on the record with RNS, but her husband, Matthew Cicero, said some teachers and alumni complained that the pins made them feel uncomfortable. “We started hearing things from the alumni association about Keziah being a problem,” Cicero said. “That’s when the microscope started focusing on Keziah and when they started monitoring her social media.”

At one alumni meeting in November 2023, a retired teacher called Keziah a “terrorist,” alleging that she supported Hamas and was indoctrinating students, he said.

As pressure mounted, Ridgeway continued to teach. That December, she assigned the Black spirituals project — a typical assignment for Ridgeway, who teaches history from a critical race theory and social justice angle.

For years, Philadelphia has been known as a bastion of progressive education. In 2005, it became the first major city to make the study of African American history a high school graduation requirement. Ridgeway, along with the district’s director of social studies curriculum, Ismael Jimenez, and teachers Norman Shaw MacQueen and Hannah Gann, belonged to the Racial Justice Organizing Committee, which began as a subcommittee of Working Educators, a reform caucus within the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. The RJOC describes itself as “a group of activists and advocates, working towards the abolition of white supremacy and racism in all of the ways it presents in our communities and schools.”

In 2017, the RJOC planned a Black Lives Matter Week of Action in Philadelphia schools, which grew into a national campaign adopted by the National Education Association and 25 U.S. cities. During the George Floyd uprisings in 2020, the RJOC released “Ten Demands for Radical Education Transformation,” among them “culturally responsible curriculum for every subject” and “mandatory antiracist training for all educators.” Philadelphia’s schools officially adopted the week of action as a districtwide event in 2021.

Ridgeway founded Philly Educators for Palestine, and with her colleagues and sister organizations such as Building Anti-Racist White Educators, the Melanated Educators’ Collective and Black Lives Matter Philly, developed an anti-racist educational model that teaches ethnic, Indigenous and Black studies at every level.

The School District of Philadelphia headquarters, right, are shown in Philadelphia, July 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, File)

Philadelphia’s ethnic studies curriculum has not faced the backlash others have elsewhere. In 2019, the California Department of Education, at the behest of the governor, created a statewide curriculum with the input of 19 ethnic studies experts that would eventually serve as a graduation requirement for the state. But conservative groups argued that the curriculum focused too heavily on racism, attacking critical race theory, while the California Jewish Legislative Caucus and other Jewish groups objected to the inclusion of Arab American studies, calling it “one-sided and antisemitic” because it describes Israel as a “settler colonial state.”

A California State Model Curriculum, developed with input from these dissenting groups, was eventually adopted in 2021. (The nonbinding curriculum is meant to serve as a guide to help districts develop their own curriculums.) The 19 ethnic studies experts who had devised the original curriculum, now dubbed the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum, resigned in protest. Since then, the Deborah Project, the Brandeis Center and the ADL, along with other Jewish groups, have filed lawsuits in courts challenging details of ethnic studies curriculums in Los Angeles, Santa Ana and other school districts across the state.

The RJOC teachers’ work in Philadelphia schools had escaped this kind of opposition until last year, when charges of antisemitism opened the way for attacks on their approach.

“What is happening in Philly is a really clear example of the larger national story, which to me is about this broader attack on teaching the truth, which began as a battle on critical race theory,” said Sanchez, who is Jewish. “It’s really about a teacher’s ability to address race and racism in the classroom.”

At first, like the other school controversies, the response to the podcast’s being banned was a local affair. In February 2024, dozens of Northeast teachers, students and parents, some organized as Philly Parents for Palestine, began turning out at board of education meetings to protest the ban and ask that the district investigate Appel, who they allege violated the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act by sharing names of students and photos with an outside organization.

Others testified about being punished for wanting to discuss what was happening in Gaza in school. “You cannot continue to not allow us to speak about genocide,” Northeast student Hazel Heiko, whose father, Jethro Heiko, leads Philly Parents for Palestine, told the board in May. “We see the reality on our phones. All of us have access to it. And that does not stop even when you are not allowing us to talk about it in school.”

Only a handful of Jewish Family Association members spoke at board meetings. According to a spokesperson for the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia, which works closely with the group, the association’s members remained largely hidden because of “fear of potential retaliation or targeting.”

Instead, the group, later renamed the Jewish American Friends and Family Alliance, wrote thousands of letters to city officials, the Pennsylvania education department and Gov. Josh Shapiro, demanding that Ridgeway and other RJOC teachers be prevented from discussing Gaza or Israel in class and from holding a planned teach-in for fellow educators on Gaza. Because the teach-in was held off site on a weekend, the district said it could do nothing about the event.

A subsequent letter from the group focused on an annual Africana studies lecture series for which Ridgeway was one of the speakers. The district reassured the group that the lecture series would be “heavily monitored.” The family association also began watching RJOC members’ social media. The RJOC teachers were also targeted by groups outside the district. Accuracy in Media, a right-wing group sponsored by school choice proponent Jeff Yass, sent trucks to Gann’s school with a billboard reading “10th Grade Teacher and Philadelphia’s Leading Antisemite.” In June, a similar truck showed up to Jimenez’s workplace and home. (Jimenez said he has not been active in RJOC since 2021.)

In July 2024, the ADL weighed in to the fight, filing a supplemental complaint to the Masterman parents’ Title VI complaint from May. The ADL filing added material focused predominantly on Ridgeway and RJOC teachers Gann and McQueen, as well as administrator Jimenez, citing their social media posts. In posts that used the word Zionism, the complaint annotated the word “Jewish,” arguing that the two terms were inextricably linked.

That same month, Canary Mission, a site that publishes dossiers on individuals and groups that “promote hatred” toward Israel and Jews on school and college campuses, published a profile of Ridgeway, which led to more online harassment, according to Cicero.

Racial Justice Organizing Committee members, including Keziah Ridgeway, center right, during a book launch in April 2025. (Courtesy photo)

The following month, Jill Altshuler, a School District of Philadelphia Jewish Family Association member, and an activist named Brandy Shufutinsky appeared at a school board meeting where Ridgeway also testified. Altshuler said antisemitism was running rampant in the district, citing Jimenez’s social media posts and RJOC anti-racism teach-ins.

“All of the above examples are of how this anti-Israel narrative is clearly making its way into the classroom by teachers who are advancing this agenda,” said Altshuler, telling the district officials that they are “responsible for allowing a generation of students who are being taught by members of your staff to hate Israel, hate Zionists.”

Shufutinsky, who is Black and Jewish, spoke remotely and said RJOC teach-ins posed a threat to Jewish families. Shufutinsky did not identify herself as the director of education and community engagement for the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values (now renamed the North American Values Institute), which focuses on “radical social justice ideology in K-12 schools as the key to fighting antisemitism.”

Shufutinsky, who does not have children in the school district, said she spoke at the board meeting because she believes all children deserve a “bigotry-free education.”

“My concern with anti-Jewish bigotry in our K-12 school system is not limited to the school district where I live,” Shufutinsky told RNS in an email.

Ridgeway then demanded the district provide training on anti-Muslim bias. After her testimony, she had a heated exchange with Altshuler and two other members of the SDP-JFA just outside the board chambers.

Meanwhile, Ridgeway’s husband said the letter writing campaign about Ridgeway had turned into trolling online. Shufutinsky began appearing in Ridgeway’s social media posts.

“They called her antisemitic, they accused her of indoctrinating her students, supporting Hamas, supporting terrorism,” Cicero said. “It wasn’t until later that we realized it was a coordinated situation — that we understood that these people were all organizing this on Facebook.”

Frustrated, Ridgeway posted on Instagram on Aug. 31: “I asked y’all nicely to leave me alone. I asked y’all nicely to keep my name out y’all mouth. Now I’m taking off the gloves. Y’all been harassing me for almost a year.” Calling her tormentors bullies, she vowed, “I’m not going to be silenced I’m not going to quit.”

She then posted the names of the five members of the family association, which included Altshuler’s name. In an Instagram story that followed, she later added emojis and the words “Ain’t no fun when the rabbit got the gun.” Four days later, Ridgeway went further. “Black owned [gun emoji] shop in or near Philly?” she wrote. “Asking for a friend.”

Ridgeway also began getting messages from Shufutinsky’s brother, who went by @joehayes976. He objected to Ridgeway’s naming people who had been posting about her, adding, “like people can’t find YOU.”

The next day, Sept. 4, Ridgeway posted, “Anything happen to me y’all know who is responsible joehayes976 of Escondido, California. He is the brother of Brandy Shufutinksy of Elkins Park who spoke at last month’s board meeting in support of Zionism. I blocked Brandy a few days ago and her brother decided to pick up where she left off. Such violent people. Crazy he wrote this as us educators are dealing with another school shooting in Georgia.”

The same day, the Deborah Project, which has represented Jewish and Israeli interests in education, filing anti-ethnic studies lawsuits in Los Angeles and Santa Clara, California, filed a complaint with the Philadelphia district on behalf of the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia, calling Ridgeway’s rabbit and gun store posts “a call to violent action.” The following day, Sept. 5, Ridgeway was removed from the classroom.

A month after the August board meeting, Shufutinsky’s organization began publishing the K12 Extremism Tracker, a Substack that tracks teachers’ and districts’ approach to Israel, including the activities of RJOC members.

Shufutinsky said the tracker “serves as a source of information for concerned parents and community members who have the right to full transparency of what’s happening in the schools that our tax dollars fund.”

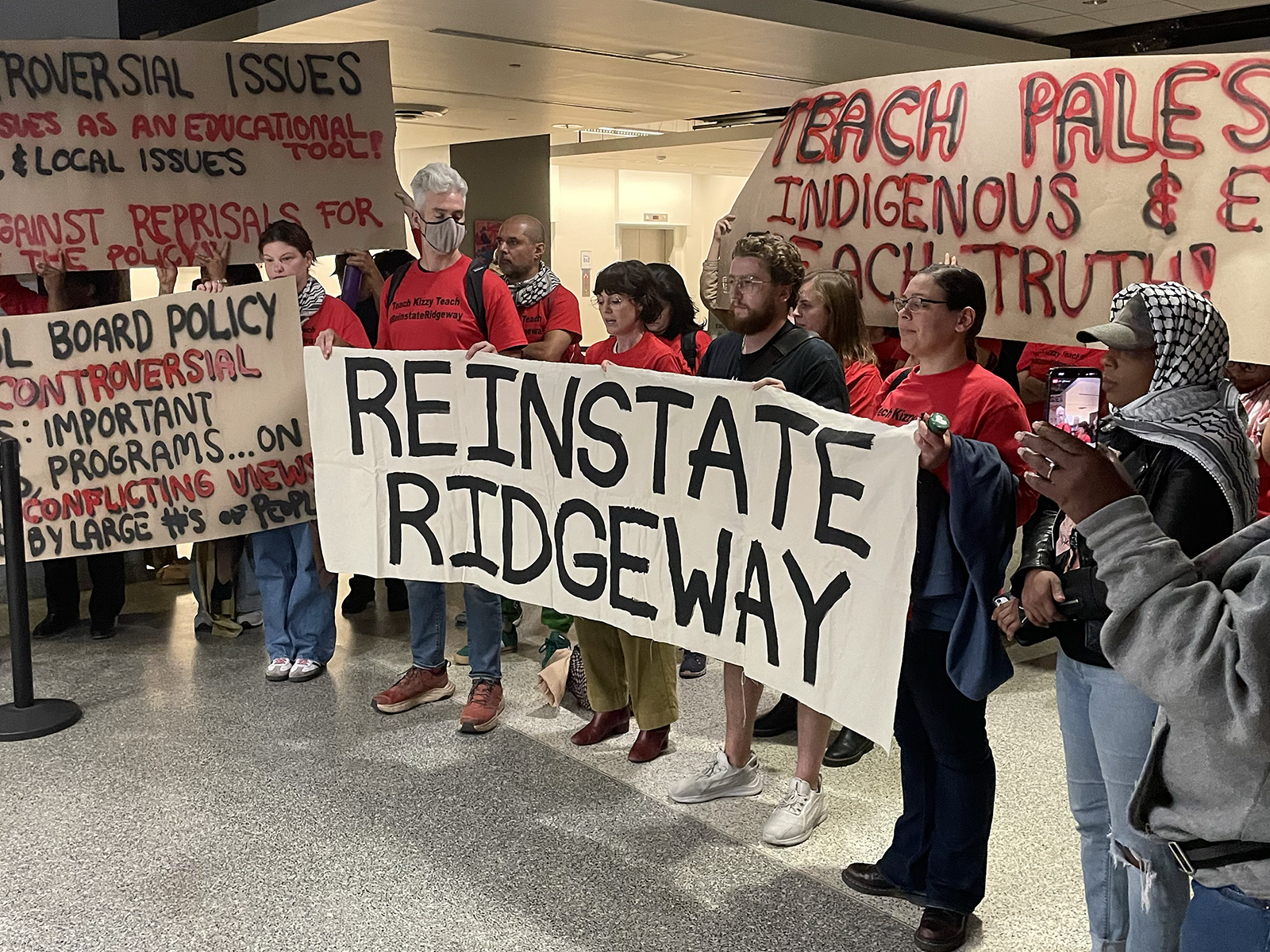

Over the next four months, those who had protested the podcast ban now began pushing school officials for Ridgeway’s reinstatement. In October 2024, having collected nearly 3,000 signatures on a petition, Philly Parents for Palestine occupied a school board meeting, arguing that the board had neglected district policy 119, which specifically encourages “discussion of controversial issues” that explores “fully and fairly all sides of an issue” to help students learn.

In deciding the Title VI complaint filed by the Masterman parents and the ADL, the DOE’s Office of Civil Rights never interviewed the teachers accused of antisemitism in the investigation, according to Cicero. In its eventual ruling, the DOE cited a teacher allegedly addressing a school assembly to criticize the decision to ban the podcast, asking the audience, “Was it really the quote-unquote antisemitism that made you uncomfortable or was it the truth?”

It says that “a teacher in a position of authority and power over all students in the school, criticizing values expressed by students and their families, during a school-wide assembly,” suggested “a hostile environment for affected students.”

The video, obtained by RNS, shows that the teacher in question was not Ridgeway, but the student who said this from the stage.

Nonetheless, the DOE ruled in December that Philadelphia had failed to protect Jewish students and required the district to develop or revise procedures to document harassment and provide training on discrimination for staff. Neither the Department of Education nor the Philadelphia school district agreed to respond to questions for this article.

A spokesman for the ADL said the organization hoped the DOE’s finding “empowers Jewish students, families, and educators around the country to speak out against antisemitic harassment, discrimination, and bullying in their schools” and called it “an important reminder to schools and universities that they cannot ignore antisemitism within their schools, particularly given the sharp spike in antisemitic incidents over the last 15 months.”

Sahar Aziz, a law professor at Rutgers Law School and author of “The Racial Muslim,” said anti-Muslim, anti-Arab or anti-Palestinian bias often goes underreported, both because of systemic biases and because Palestinian, Muslim and Arab communities lack resources to support their own legal organizations.

The emphasis on antisemitism has grown with the return of the Trump administration. In February, the U.S. House of Representatives proposed the Antisemitism Awareness Act of 2025, which would direct the DOE to use the IHRA definition when investigating campus antisemitism, despite similar bills being struck down more than a dozen times over the last decade.

Last year, the ADL, along with the Brandeis Center and pro-Israel group StandWithUs, launched Legal Protection K-12 Helplines to provide pro-bono legal assistance to families in California, Massachusetts and New York experiencing antisemitism.

In the last few months, Jewish organizations have set up new offices and organizations in anticipation of future battles on the rise of antisemitism. In October, the ADL announced the launch of the Ronald Birnbaum Center to Combat Antisemitism in Education “to compel educational institutions to drive coordinated advocacy across K-12 schools and universities to address rising antisemitism.”

In February, the Brandeis Center announced the creation of the Center for Legal Innovation, which will litigate cases of antisemitism in the workplace, housing, health care and educational centers, and the opening of a satellite center in Los Angeles.

Jethro Heiko, center, speaks during a demonstration outside the School District of Philadelphia headquarters, May 30, 2024, in Philadelphia. (Courtesy photo)

“As a Jewish person, part of what these groups are doing at our school is against my wishes,” said Jethro Heiko, a Northeast parent who leads Philly Parents for Palestine. “I don’t want to center Judaism, but I do think it’s really important that Jews who understand antisemitism say that we need to distinguish between criticizing Israel and antisemitism.”

He said he is also disturbed by the alignment of Jewish Zionist organizations with the political right. “It used to be like a Venn diagram that had a little bit of overlap,” he said. “Now they’re really aligning. So it’s like these two circles, they’re getting closer and closer. It’s almost to the point where like they’re hard to distinguish.”

The battle over what can be taught in Philadelphia’s classrooms is not over.

In December, Ridgeway, along with Gann, Sanchez and Nick Palazzolo, published “Teaching Palestine-Israel From the Perspective of Civil Rights and Black Power Activists” for the Zinn Education Project. The 23-page lesson plan “highlights the complexity and diversity of thought as Civil Rights and Black Power leaders and organizations developed their views on Palestine-Israel.”

Meanwhile, K-12 Terrorism Tracker continues to blog about Ridgeway, Jimenez and other members of the RJOC. The most recent posts include an announcement that Heather Mizrachi, a curriculum specialist, has sued the district for harassment and one about Jimenez running a “revolutionary workshop” at a Swarthmore pro-Palestine encampment. Jimenez said he did not take part in the workshop.

A couple weeks ago, Ridgeway posted a photo of a School District of Philadelphia ID badge on Instagram with the words “Ya Rabbi ” (“Oh, My God” in Arabic), suggesting she may be returning to the classroom. It’s a development many in the Northeast community have looked forward to, for themselves as much as for Ridgeway.

“It’s so important for Miss Ridgeway to come back because if she doesn’t, that proves a point to everyone: Look what could happen to you if you talk about Palestine,” said Rouz Lami, the mother of Sedeen and a current Northeast student. “Growing up, I was told, don’t say you’re from Palestine, or you’re gonna get in trouble, or else you’re gonna get mistreated. And that’s what they’re doing now.”

This story has been updated with additional comments.

This story was reported with funding provided by the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation.