(RNS) — July 10 marks 100 years since the start of the Scopes monkey trial, the famous court case in which teacher John T. Scopes was prosecuted for violating the Butler Act, a Tennessee law that prohibited teaching evolution in public schools.

Dubbed “the trial of the century,” the case received unprecedented coverage by the mass media. It was the first to be broadcast live on radio and dispatches from the courtroom were sent across the globe hourly, as a world increasingly moving toward modernity and secularism watched to see how religious traditionalism and fundamental faith would fare.

The trial’s cast of characters heightened the drama. Clarence Darrow, the acclaimed attorney and staunch agnostic known for his civil libertarianism, served on the defense. William Jennings Bryan, a former populist presidential candidate known as a religious fundamentalist, was the prosecutor.

Of equal impact on the trial’s enduring legacy was the progressive media pundit and atheist Henry Louis Mencken of The Baltimore Sun. We have Mencken to thank for the moniker “monkey trial,” as well as for coining the term “Bible Belt.” His dispatches helped shape the national and global understanding of both religious fundamentalism and its proponents for decades to come.

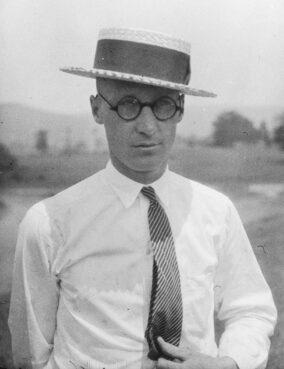

Teacher John T. Scopes in 1925. (Photo by Watson Davis/Smithsonian Institution/Creative Commons)

The stage on which this legal theater played out was a sleepy little town called Dayton, Tennessee. Nestled amid the hills and ridgelines of the Cumberland Plateau in greater Appalachia, Dayton was by no means a passive player in the drama. Town leaders manufactured the trial as a way of bringing publicity and much-needed commerce to the economically declining town.

The case was meant to be a show trial all along. Scopes sat in the defendant’s seat, but it was the compatibility of religion and modernity that was truly on trial for the American public. And many in media, including Mencken, seemed intent on ruthlessly prosecuting the very people who clung to the faith in question – namely, the people of Dayton.

I spent most of my growing up years in Dayton, my childhood under the shadow of the trial and the outside world’s understanding of it. My own evolution has involved a deepening understanding of the trial’s impact on the religious landscape in America, but also on the people I called neighbors and friends.

Before 1925, the stage had been set for Dayton. Scope’s case unfolded in Appalachia at a time when the image of the backward, deviant “hillbilly” was becoming firmly established in the American imagination. The proliferation of this archetype had been helped by the wildly popular genre of “local color” travel stories published about the mountain South in the late 19th century. Meant to be entertaining rather than factual, these magazine fables painted the residents of Appalachia and the Ozarks as either aggressive degenerates whose Scots-Irish heritage had predisposed them to a clannish culture of violence and never-ending feuds, or as bucolic simpletons whose isolation in the hills had rendered them the quaint embodiment of a primitive American past. Both tropes suggested the indigent ways of mountaineers were an impediment to American industrial, social and intellectual advancement.

By the time of the trial in 1925, hundreds of silent films had picked up on the money-making potential of these hillbilly caricatures. The entertainment industry captivated audiences across America with storylines featuring moonshiners, feuding outlaws and simpleminded but alluring mountain maidens, with the Southern mountains serving as a titillating setting where indolence and civility clashed.

So, when Mencken descended upon Dayton with his pen and paper, the mental image of the rural, religious imbecile was already easily accessible for most Americans. He described the townsfolk as “hillbillies,” “halfwits,” “peasants,” “yokels from the hills” and “gaping primates from the upland valleys of the Cumberland Range.” These admirers of Bryan’s religious fervor, Mencken noted, were “people who sweated freely, and were not debauched by the refinements of the toilet.”

Though Mencken’s writings have been described as satire, most news outlets offered a similar take, portraying the trial as a joke and the townsfolk as worthy of ridicule.

Defense attorney Clarence Darrow, left, and prosecutor William Jennings Bryan speak with each other during the Scopes monkey trial in July 1925, in Dayton, Tenn. (AP Photo, File)

What Mencken failed to note was why the town leaders felt compelled to generate interest in the town. Dayton was experiencing a significant economic downturn, due in part to the failing coal industry. Many of these “hillbillies” had mined the coal that forged the steel and turned the lights on in Mencken’s grand East Coast metropolitan hubs of progress and intellect. Dozens of them had died doing so, with Dayton seeing three major mine accidents in the decades prior to the trial.

Coal did to Dayton what it has done to countless towns across Appalachia — create a boom-and-bust economy in its wake, not to mention blackened lungs and grieving families. It is a legacy that was largely omitted in a more recent think piece on mountaineers, now-Vice President JD Vance’s “Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Region in Crisis,” which became the de facto textbook on Appalachia for urban elites. The book only touched briefly on the devastating impact of extractive industries on the region. Instead, Vance relied on the same stereotypes as Mencken.

Fundamentalists of faith were accused by Mencken and his contemporaries as purveyors of bigotry and intolerance. This accusation could be seen as hypocritical coming from Mencken, who embraced social Darwinism and believed in a clear human hierarchy. He wrote, “The human race is divided into two sharply differentiated and mutually antagonistic classes … a small minority that plays with ideas and is capable of taking them in, and a vast majority that finds them painful and is thus arrayed against them.”

Referring to these “inferior orders of men” as “Homo Neanderthalensis” and “immortal vermin,” he wrote: “The inferior man’s reasons for hating knowledge are not hard to discern. He hates it because it is complex — because it puts an unbearable burden upon his meager capacity for ideas.”

Bryan’s adamant objection to the teaching of evolution in school had less to do with its complexity and more to do with the moral implications of the theory. “The Darwinian theory,” Bryan wrote, “represents man as reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate — the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak.” He stated that he believes the law of love as outlined in the Bible, rather than the law of hate, is what leads to true progress.

Mencken maintained little love for Bryan, whose eyes he described as “sinister gems” and “blazing points of hatred.” Mencken wrote, “he was a peasant come home to the dung pile,” and insisted Bryan and all who followed him were an existential threat to the nation’s advancement.

The day before the conclusion of the trial, after Dayton had already become “a universal joke,” Mencken wrote, “Dayton, of course, is only a ninth-rate country town, and so its agonies are of relatively little interest to the world.”

But the town’s agonies matter to me. Appalachians have too often been reduced to a rhetorical device, supposed cyphers by which progressives understand populism and conservatism. Cast as the embodiment of yesteryear’s ignorance at whom a modern-minded public can direct its ire, they are rarely represented with the nuance their diversity and dynamism demand.

My late sister, New York Times bestselling author Rachel Held Evans, struggled as I have to make sense of the trial and its enduring impact on our hometown. It was her shifting perspective of Bryan and her growing misgivings about religious fundamentalism that led her to write her debut memoir, “Evolving in Monkey Town” (re-released under the title “Faith Unraveled”), and the book’s success is a testament to the complexity of the trial’s legacy.

Mencken’s coverage of the trial helped explain the legacy of mistrust for mass media among the rural and religious. But it also offers a vivid illustration of how prone we are to make our political and religious adversaries caricatures rather than contextualized characters with complicated stories, unique insights and real convictions.

Perhaps the trial’s most lasting legacy is the precedent it set for how we engage with our ideological enemies and the role the media play in that discourse.

The real loser in the aftermath of the trial may not have been John T. Scopes, who was convicted. Nor was it the evolutionists, who never saw the case make it to the Supreme Court, or even the anti-evolutionists, who became the butt of the national joke. Rather, our discourse itself suffered perhaps the most defeating blow.

(Amanda Held Opelt is an author and songwriter living in the mountains of Western North Carolina with her husband and two young daughters. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)