NEW YORK (RNS) — As United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement has intensified activity across New York City, faith-based shelters, food assistance programs and spaces intended to be safe for immigrants are quietly adjusting how they operate. Though ICE has not yet raided a religious institution in the city, staff and clergy said the risk seems urgent.

Some are weighing legal protocols, scaling back services and preparing for the worst, they told RNS.

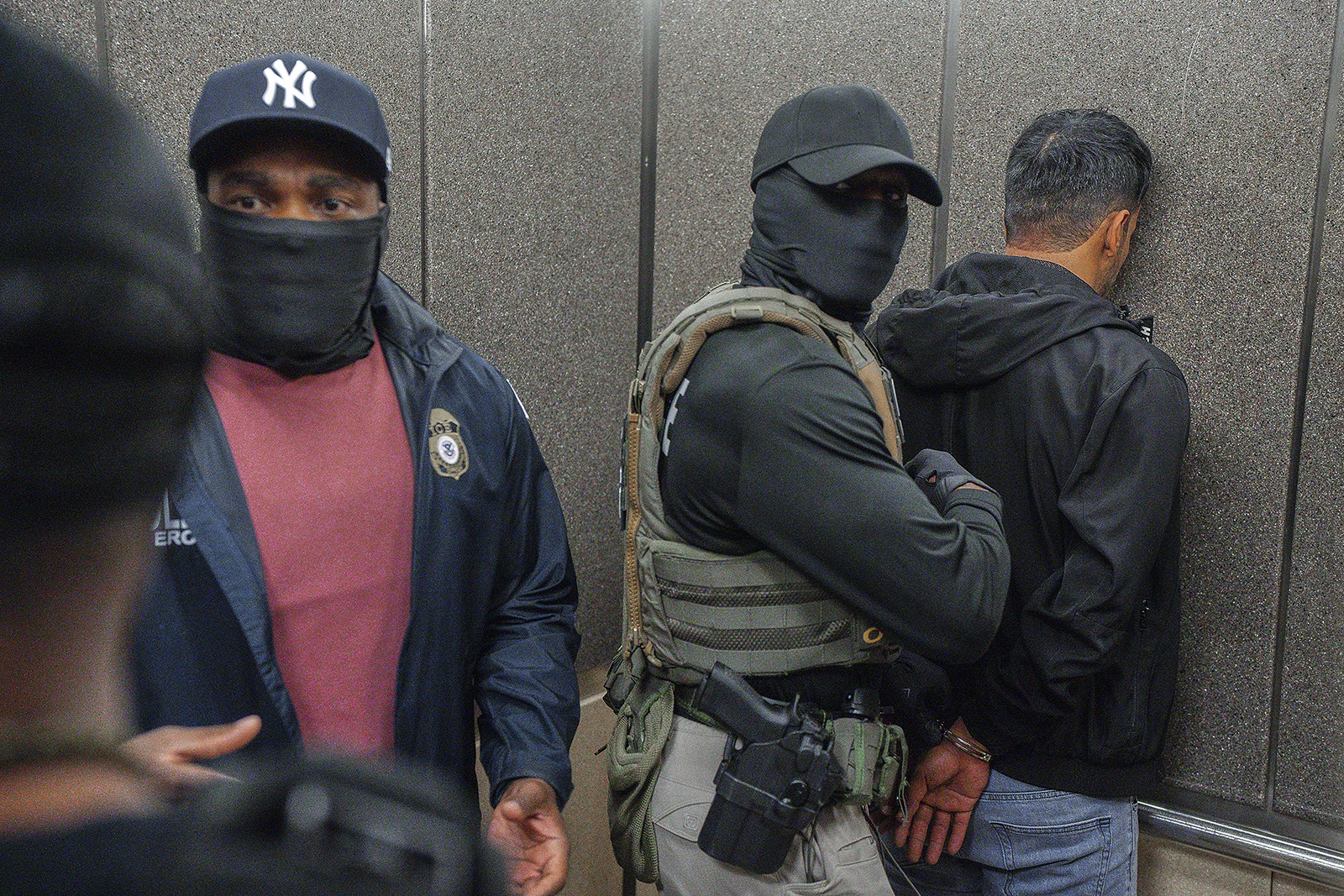

In April, 206 people — referred to as “illegal aliens” by ICE — were arrested during a five-day sweep across the New York metro area. Last month, an ICE agents were reported in the parking lot of a Southern California Catholic church, prompting the local bishop to lift the Sunday Mass obligation for those fearful of attending services.

Since President Donald Trump began his second term in January, immigration arrests have increased across the country and more than doubled in 38 states.

Since January, Imam Musa Kabba has reconsidered operations at Masjid-Ar-Rahmah, the Bronx mosque he has led since 1999. For years, the mosque served food daily and stayed open late into the night, functioning as both a house of prayer and safe gathering place for newly arrived immigrants. Now, fearing ICE visibility, the doors close daily at 9 p.m., and food is only offered on weekends, he said.

“We tell migrants to slow down and not to come to the center all the time,” Kabba said. “Or if they come, they should not stay long, like many used to.”

ICE has said it focuses on arresting individuals with prior deportation orders or criminal records and that its actions are targeted. However, according to NPR reporting, at least 56,000 immigrants were being held in ICE detention as of early July, and about half do not have criminal convictions. Trump administration federal policy changes have also blurred the lines of where arrests can happen, allowing them at locations previously protected under long-standing sensitive locations guidance, like houses of worship and schools.

Central Park and the New York City skyline. (Photo by Leonhard Niederwimmer/Pixabay/Creative Commons)

Immigration enforcement agents do not legally need a judicial warrant, issued by a court, to make an arrest in a public space. If they have reason to believe someone is in the country unlawfully, they can detain the person on the street. However, entering private areas like offices, kitchens or the grounds of a mosque or church requires a signed judicial warrant. Still, immigration advocates warn that many agents present administrative warrants from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security instead, which do not authorize entry.

That distinction has shaped recent training sessions at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen in Manhattan, the largest soup kitchen currently operating from the grounds of an Episcopal church in the city.

“We certainly have done some internal preparations just so that our staff knows what to do in the event that [immigration agents] show up,” said Elizabeth Starling, Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen director of development. “We went through a training about the need for them to have a specific judicial warrant because, well, you’re not coming on our property for a fishing mission — that’s not going to happen.”

Since February, Holy Apostles staff, who serve 750 households each week through its soup kitchen and food pantry, have been trained to identify legitimate warrants and instructed never to allow agents into private areas without them. Additionally, entrance to the church is prohibited without a manager of the soup kitchen present.

“We made it abundantly clear to staff, [ICE] is not coming in our building until somebody from a managerial capacity is interceding,” Starling said.

Holy Apostles hasn’t changed its day-to-day services and is still providing daily grab-and-go meals; it also operates a “choice pantry,” where visitors grab groceries from kiosks three days a week. However, Starling said the new precautions hinge on readiness and dignity. “It’s really disheartening to see just this sort of stoking of fear about the other … it just seems very un-Christian,” she said. “We’re doing what we can to help the folks who are coming to us, and we’ll continue to do so boldly.”

While Masjid Ar-Rahmah has a multicultural congregation, its majority is West African immigrants. In recent months, the number of people coming on the weekends for meals has significantly dwindled, Kabba said.

“Sometimes only three people will come,” he said. In the not-so-distant past, Kabba said the mosque served dozens on a regular basis.

“Since the election, we can tell there’s fear in the community,” Kabba added. “They don’t stay because they don’t know when ICE might show up. ICE doesn’t tell you when they’re coming.”

Still, Kabba said he’s remaining hopeful. “We pray the help will come from God and will help his immigrant people to freedom from any kind of terror or any fear,” he said.

Brennan Brink, associate director for migrant outreach at the Interfaith Center of New York, works with more than 100 congregations across the five boroughs, many of which are led by immigrants or have a long history of offering refuge to New Yorkers in need. Many faith leaders the ICNY works with are reviving precautions instituted during Trump’s first term, Brink said, like posting signs that read, “ICE activity is not welcome here. We are a community that welcomes all.” The aim is for the signs to serve as a visual reminder that the space is private property, helping discourage uninvited entry, he said.

Brink said more and more faith-based organizations are still serving congregants and others in need but choosing to stay under the radar.

“There’s some people who would probably have been happy to talk to a reporter a year ago who now would much rather continue to do the work that they’re doing, but just have it be known throughout the neighborhood,” Brink said. Some congregations are aiming to limit their visibility, avoid any outside attention and clearly mark the limits of access, all to protect vulnerable visitors.

“There’s definitely a general climate of fear that has increased in the past few months,” Brink said. “Not necessarily based on actual ICE presence, but just people hearing what’s happening elsewhere and being scared that they’re next.”

This article has been updated to clarify the number of ICE arrests reported in a church parking lot in June.