(RNS) — Protesters were dressed in national colors, holding Bibles and signs with crosses, singing Christian hymns and shouting battle cries as a mob violently invaded and vandalized the federal government’s headquarters. This scene of red, white and blue is familiar to audiences in the United States, recalling the events of Jan. 6, 2021. But for those more familiar with the political landscape farther south, the scene might instead feature green and yellow in Brasília, Brazil, two years later, on Jan. 8, 2023.

“Apocalypse in the Tropics,” a new documentary by Oscar-nominated director Petra Costa, released on Netflix on Monday (July 14), shows footage of the latter uprising in exploring the intersection of faith, politics and power in the country. The film follows five years of political developments in Brazil, which elected far right President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018, with massive evangelical support. Under his administration, the country endured the COVID-19 pandemic, witnessed an alliance between religious leaders and the federal government strengthen, and saw violent attacks on democratic institutions after his electoral defeat.

The consequences of Brazil’s religious transformation and its relation to the configuration of political power are investigated in the film. Alessandra Orofino, the film’s producer and co-writer, spoke with RNS about the parallels between the politics of Brazil and the U.S. and about what the documentary aimed to capture.

“The rise of religious fundamentalism as a powerful force in authoritarian politics is a vital component of democracies’ deterioration in Brazil, in the U.S., in Hungary and India, in Israel, and many places around the world,” she said. “So we hope that (this film) is part of the debate that will go beyond Brazilian borders and help people around the world and invite them to have this conversation.”

Costa, a Brazilian filmmaker, began her career making more intimate, personal films. In “The Edge of Democracy” (2019), which was nominated for an Academy Award, she preserved that tone by weaving Brazil’s recent political crisis, which she interpreted as the erosion of a young democracy, with her own family’s history as the daughter of left-wing activists persecuted by the military dictatorship, and the granddaughter of a businessman tied to the political and economic elite.

“Apocalypse in the Tropics” film poster. (Image courtesy of Netflix)

“Apocalypse in the Tropics” works almost as a sequel. But this time, Costa immerses herself in a world less familiar to her: evangelical Christianity — which has become increasingly decisive in shaping Brazil’s political future.

The connections between Brazil and the U.S. reflect decades of transnational circulation of ideas, theologies, strategies and resources involving missionaries, Christian publishing houses, seminaries and religious think tanks. It’s a story of mutual influence, but also of dependence and asymmetry.

A predominantly Catholic country since its colonization, Brazil has experienced a rise in evangelicalism that is one of the more striking religious transformations in recent decades. In the 1970s, around 5% of the population identified as evangelical, while today, about 27% of Brazilians do, according to 2022 census data released last month. Catholics, who 30 years ago represented more than 80% of the country, now make up a little more than half of its population.

The most visible result of the Cold War in many Latin American countries was the rise of military dictatorships, supported by the U.S. and fed by fear of communism, which the documentary looks back on to understand the roots of the evangelical growth. In Brazil, the dictatorship lasted from 1964 to 1985, a period when evangelists such as Billy Graham had strong influence and when seminaries and churches often received direct and indirect support from U.S.-based institutions.

“The influence of American evangelicalism and the American government in the rise of evangelicalism in Brazil is a very interesting frame of analysis to understand the growth of the movement,” Orofino said.

American audiences can learn from the documentary in two ways, the producer said. The first is by “seeing themselves reflected in this kind of weird mirror that is Brazil.” Second, they can gain a “better understanding of how these networks of power, in many ways, use the resources and the centrality of the American government to impose, or at least to influence, the political life of other countries,” she said.

In a country marked by extreme social inequality, evangelicalism has expanded rapidly among low-income Brazilians. At a Q&A after the film’s screening at DOC NYC last Wednesday (July 9), Costa and Orofino spoke about the role churches play in people’s lives. They discussed how social and humanitarian aid networks are sometimes used to reinforce political power projects led by church leaders.

“Apocalypse in the Tropics” director Petra Costa, center, and producer Alessandra Orofino, right, participate in a Q&A after a DOC NYC screening of the documentary, July 9, 2025, in New York. (Photo by Helen Teixeira)

Churches “form solidarity networks and create community around them,” Orofino said. “Their leaders have a strong presence locally, in territories where they know the families, the people who live there, supporting them through difficult times. And in many ways, that’s lacking from so many of our democratic movements, and people are looking elsewhere for that kind of connection.”

Often, the price of that presence is political influence, they explained. As Costa pointed out, in 2018, “70% of evangelicals voted for Bolsonaro. That’s more than any other segment of the population.”

“I really do believe that the evangelical base itself will become more attuned to the fact that the people who are representing themselves as their leaders and amassing enormous amount of political power in the process are not even true reflections of what the communities of faith actually look like,” Orofino said, noting that while the evangelical base is largely made up of women, Black Brazilians and working poor citizens, its leadership continues to be dominated by white men from Brazil’s wealthier urban centers.

The question that’s then raised, Orofino said, is, “How can we offer alternative versions of that – forms of community that could be spiritual as well, that are not intrinsically authoritarian and do not try to bridge that separation of church and state?”

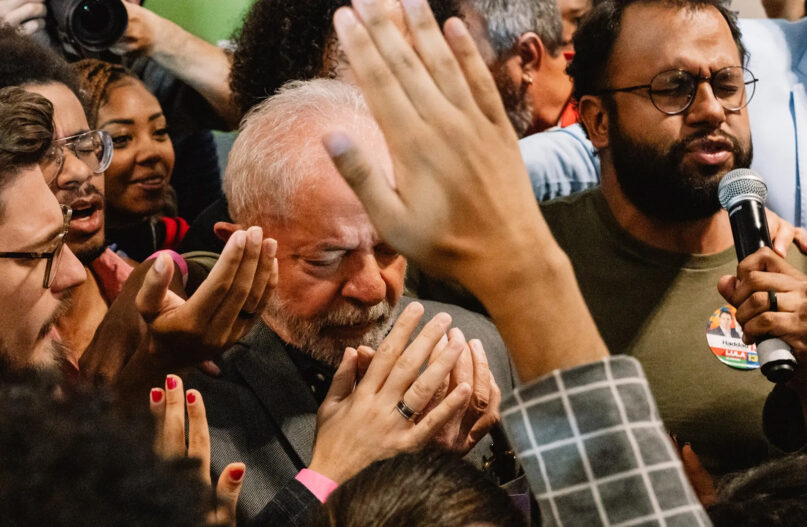

They also addressed internal tensions within evangelical communities. “There are other progressive pastors who have been shunned and persecuted by their churches because they declared that they would not vote for Bolsonaro or declared support for Lula,” Costa said, referring to Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. “So that is religious persecution, and that’s the reason why the separation of church and state was invented — to protect Christians from religious persecution. It was Christians who invented it, and we’re seeing it play out in Brazil.”

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, center, in the “Apocalypse in the Tropics” documentary. (Photo courtesy of Netflix)

For Costa, this dynamic is at the heart of the film’s message. “It was this destruction of democracy, and that’s what the film is about,” she said.

Throughout the documentary, the theme of the apocalypse serves as a narrative thread through which the film examines how literalist interpretations of the Book of Revelation, with its ultimate battle between good and evil, have shaped political imaginations and been absorbed into real-world political ideologies.

“It’s very hard to overstate the importance of the Book of Revelation and those symbols in our politics today,” Orofino told RNS. “Not only as a seminal book for dominion theology, but also as a force … that then has very concrete influence over geopolitical events around the world. So, it’s really illuminating for us.”