(RNS) — When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June that Maryland’s largest public school district must allow parents to opt their children out of lessons if those lessons conflict with “sincerely held religious beliefs,” the decision was lauded as a win for Muslim, Catholic and Orthodox Christian parents who oppose teaching about LGBTQ inclusion in public schools.

Hindus were not strongly represented among supporters of Mahmoud v. Taylor, in part due to Hindu theology, according to Yagnesh Patel, director of the Hindu Parents Network. “There is no problem with embracing diversity, and support for inclusion of multiple perspectives: That’s an essential part of Hinduism.”

If Hindu parents have concerns about school curriculums, Patel told RNS, it’s how Hindus themselves have been portrayed.

Hindu Parents Network, a project of the Hindu advocacy organization Coalition of Hindus of North America, offers virtual workshops on Hinduism for grade-school kids, as well as support groups for first- and second-generation Indian American parents who object to what their kids are absorbing about the faith at school, from ideas about worshipping idols to stereotypes about sacred cows.

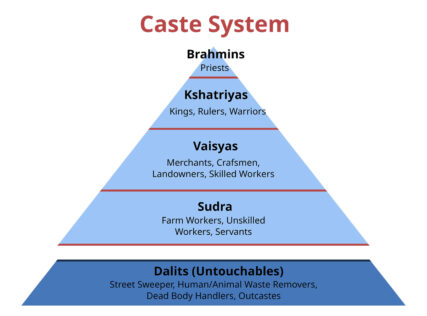

Foremost on these Hindu parents’ minds is the explanation of caste, the hierarchical social structure in India and other places that divides people by language, culture and class. For decades, Hindu parents have complained about a “caste pyramid” visual aid commonly used by teachers, with Brahmins at the top and Shudras, or “untouchables,” at the bottom, that they say simplifies the ancient system to a harmful degree.

The controversial Caste System pyramid, as seen in many textbooks. (Image courtesy Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

“There is a wrong understanding here, and it is based on the colonial understanding of Hinduism,” said Patel. “It is coming all the way from 18th and 19th century scholarship by colonizers. We want to correct this understanding.”

Smitha Raj, a parent of a teenager in an area in New Jersey with a large South Asian population, said she has heard of a classroom activity in which students were randomly sorted based on caste, and made to “act out” untouchability.

“I come from a Bahujan family,” Raj told RNS, referring to a lower, or Dalit, caste. “So, to me, that my son is learning the idea that somehow there is a pyramid and we are at the bottom of the pyramid, and somehow he is inferior to somebody else in his class, or in our neighborhood, or maybe in our friend circle, that was quite appalling to me.”

In the early 2000s, the Hindu American Foundation, another Hindu advocacy organization, proposed changes to middle school social studies textbooks: notably, to change mentions of caste to either “varna” or “class.” In 2017, a California court rejected two textbooks that were deemed problematic and accepted HAF’s edits to others. At the time, educationist James Andrew LaSpina recommended that educators become “prudently aware” of the Hindu American community’s concerns over the portrayal of their history, religion and culture.

Caste has long been a contentious topic among Hindu immigrants. In 2023 in California, a bill adding caste to anti-discrimination laws led to protests and ultimately a veto by Gov. Gavin Newsom, but some colleges and universities have instituted caste discrimination bans. To Raj, Hinduism teaches karma: that the “choices we make, our nature and the discipline we have molds us into the person we can grow up to, not some random, birth-based order.”

Mitch Siegler, CEO and founder of the nonprofit THINC Foundation — a name based on the acronym for “Transparency, Honesty, Integrity in the Classroom” — circulated a social media video earlier this year in which a Hindu student detailed his experience with being singled out for practicing casteism at school, despite not knowing his own status.

According to Siegler, the COVID-19 pandemic alerted many parents for the first time to what their children were being taught under inclusive or ethnic studies curriculums, causing “great damage to the trust of educational institutions, when parents looked over on their kids’ screens and saw what they were being taught.”

Raj said another cause for parental concern is the influence of social media. Racism against Indians and Hindus is not uncommon in the social media world, she said. “Our kids grow up actually imbibing all those stereotypes. So to correct these biases is a big challenge.”

Aarushi Nohria, a Chicago-area public high school teacher who grew up in a Hindu family, discerns what she calls an “orientalist spin” toward India and Hindus in popular culture. “So, of course, it’s also true in the education system,” she said, recalling hearing one of her own middle-school history teachers comparing polytheistic Hindus to barbarians and heathens.

Nohria worries that Hindus who object to caste being taught as part of Hinduism may be benefiting from their own caste identity and are therefore unwilling to confront how caste dynamics persist. Many immigrants, she added, are trying to uphold a reputation as a “model minority” and want to avoid the taint of casteism.

Parents may be best served by countering what their children are hearing at school in Sunday school lessons at their temples, or in family conversations about India’s complicated history, Nohria said. “I think, ultimately, education is very communal,” she said. “One of the important things that I’ve come to realize as a teacher is that school is so deeply important, but the learning that comes from extracurricular activities can actually have the potential to be so much deeper.”

Mangesh Patnaik, a parent of two high schoolers in Bethesda, Maryland, said school is not the only place children learn — it is in parents’ hands to fill in the blanks. “That’s what parenting is. ‘Hey, you know what? Maybe the school is saying this, but here’s what I think it is, and here’s why I think it is what it is,'” he said. “You should be able to have that conversation with your children and share more perspectives.”

(Photo by RDNE Stock project/Pexels/Creative Commons)

Some Hindu parents, of course, are as concerned as conservative Muslim or Christian parents about what their children are being taught about LGBTQ inclusion. Priya Subramaniam, the mother of teenagers in the San Francisco Bay Area, said traditional Hindu parents who are unhappy with LGBTQ+ books in schools are “easy to find.”

“I hear it every day,” said Subramaniam, who calls herself a liberal. “I’ve reached a point where I’m tuning it out.”

But she nonetheless believes defining people by their ethnic identities “can be exploited” and lead to further divisions. “I don’t call myself an Indian or an American, and my kids feel the same way. I think a lot of our conflict is when we take a definitive stand, thinking these identities are the ones that define us. There are times when we have to go above and beyond and just keep to humanitarian values. As long as that defines us, we should be fine.”

Patel, of the Hindu Parents Network, has two middle schoolers and said Hindu Americans often “overfocus” on academics, rather than social and cultural belonging. He and his wife, he said, “realized that, at one level, it is fine. You have to be professionally successful, that is a given.

“But at the same time, you have to have a balance, you need to know how to live (a) meaningful life. And that comes from spiritual teaching, from their Hindu heritage. So that balance is something we feel like the community needs to understand.”

Nishant Limbachia, a parent from New Jersey, goes further, saying that much of the next generation’s learning will come from the students themselves, rather than the immigrant parents who may not fully understand the Hindu American experience.

“The next generation needs to own up and carry the baton,” he said. “These are Hindu children, and they would have to carry the Hindu values to able to be successful in this world, because the coming time is really turbulent, as far as I can see. A grounded value system, which the Hindu value system provides, is really needed.”