(RNS) — San Diego Auxiliary Bishop Felipe Pulido noticed the way a father held his young daughter and stood close to his wife and teenage daughter in the courtroom. The love and care they had for each other was palpable on Tuesday (Aug. 12), when Pulido accompanied the asylum-seeking family for an immigration court hearing.

“As an immigrant, I got emotional because of that connection I have with my own family — I put myself in his shoes,” said the Catholic bishop, who was born in the Mexican state of Michoacán before immigrating to Yakima Valley in Washington as a teenager. He finished high school there, worked picking produce and eventually was ordained a priest.

Immigrants are facing court appointments with newly heightened levels of fear as the Trump administration has begun sending agents to detain migrants as they leave the courtroom. If immigration judges dismiss their cases, they can immediately face expedited removal proceedings without a chance to make their case for asylum. Previously, a 10-day response time to the dismissal was allowed.

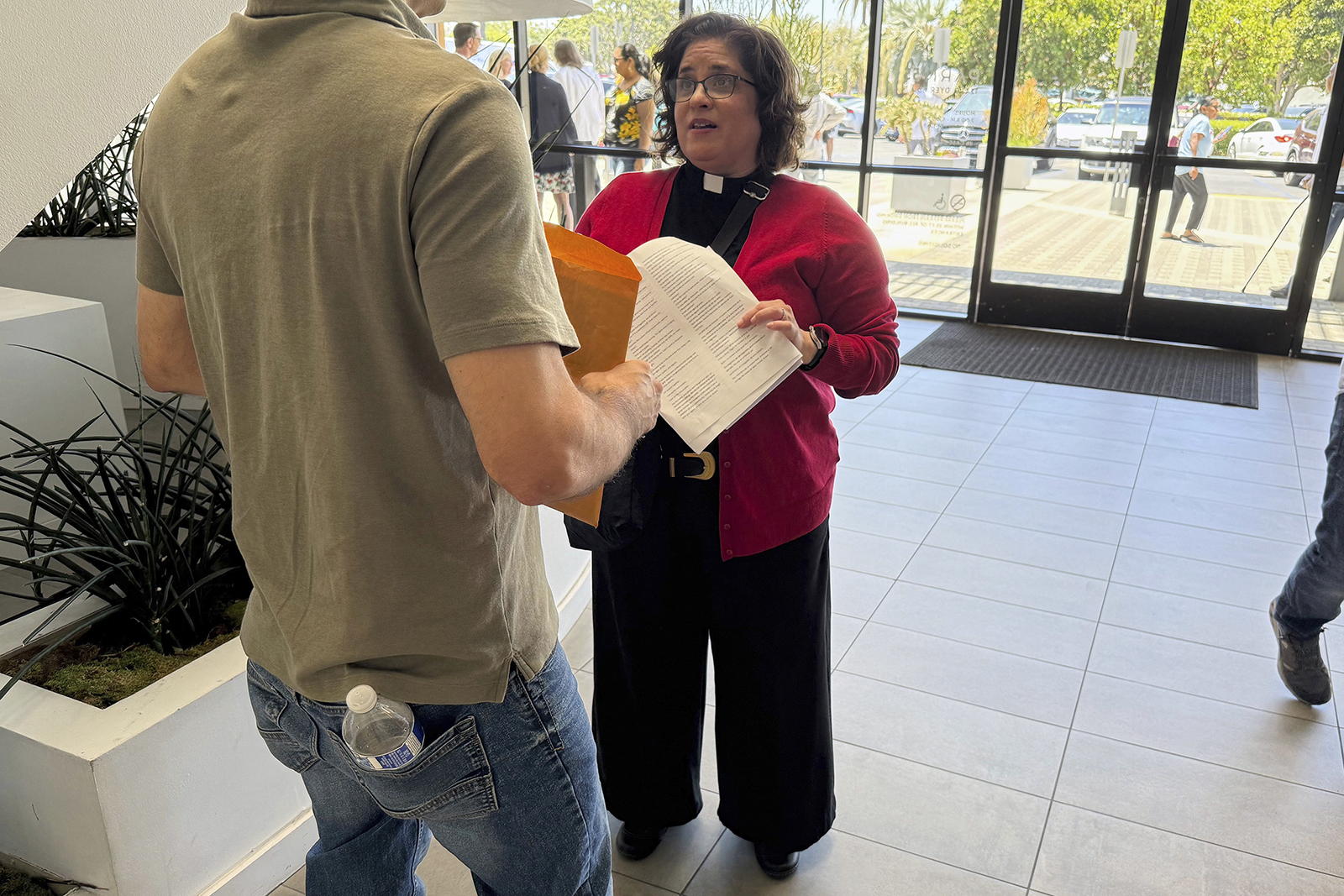

Guided by their faith, clergy like Pulido and other representatives from religious groups are accompanying immigrants to court appointments to provide comfort and information and, in cases where their worst fears are realized, to pick up the pieces of a shattered American dream.

The Rev. Noel Andersen, national field director at Church World Service who is ordained in the United Church of Christ, holds a weekly call on faith-based court accompaniment. He told RNS that through accompaniment, “Faith leaders bear witness and speak out against the ways masked ICE agents are abducting our community members.” Accompaniment is taking place “in every major city and in some rural areas, just about everywhere there is an immigration court,” he said.

San Diego Auxiliary Bishop Felipe Pulido. (Photo courtesy of the Diocese of San Diego)

When it was time to leave their San Diego hearing, Pulido said, the family saw half a dozen United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, and the mother told him she was scared. The bishop stuck close to the family, talking and reassuring them as they walked by the agents, he said. The judge had given them another hearing in December.

Pulido was present because the San Diego Catholic Church has partnered with Episcopal, Lutheran, Jewish and Muslim clergy, as well as lay people, to provide accompaniment for immigrants at the courthouse every day in August. They have more than 50 volunteers, and as more sign up, they’re planning to continue the ministry.

It was only when they’d gotten through the ordeal safely that the family asked Pulido which church he was with. The Catholic family were stunned to learn a bishop had accompanied them that day, he said.

Pulido said he was inspired by Pope Francis’ words last year when he attended “baby bishop camp,” an orientation for new bishops in Rome, to get involved in the court accompaniment ministry. “Be a sign of hope for the homeless, for the migrants, for those who are in prison,” he recalled Francis saying.

He said he believes sometimes ICE agents choose not to detain migrants even after their cases are dismissed because his priests are walking with them, though they have also witnessed detentions.

Pulido isn’t the only Catholic bishop who has gone to immigration court. In Orange County, where priests and deacons are also accompanying the faithful in immigration court, Bishop Kevin Vann attended the July bond hearing of Narciso Barranco, an immigrant without legal status and father of three U.S. Marines who was filmed being beaten in the head by immigration agents during his June arrest.

El Paso, Texas, Bishop Mark Seitz was also in immigration court on Tuesday, said Scalabrinian Sister Leticia Gutiérrez, the director of the diocese’s migrant hospitality ministry.

Seitz witnessed the detention of three people — “the sobbing, the anguish of the wife of one of them,” said Gutiérrez in Spanish. Seitz told her, “I saw Jesus walking through the hallway, sister, defenseless.”

Gutiérrez, who has organized a precise system for the diocese’s immigration court accompaniment in the last two months, arrives at immigration court at exactly 7:50 a.m., four days a week, and stays until the final cases have concluded.

Before ICE agents arrive (about 20 minutes after she does), Gutiérrez and a priest who is a retired immigration lawyer introduce themselves to migrants arriving for court and provide them basic legal advice and information — and try to sit with them in their anxiety.

While some of the diocesan team members observe the court sessions, ICE agents have also allowed them a protected zone in the waiting room, so when immigrants leave their court appointments, Gutiérrez helps them arrange their affairs, sometimes taking up to 30 to 40 minutes before they walk toward the agents. She encourages them to call their families one last time and share their Alien Registration Number, and then to write phone numbers on their bodies so they can call family if they’re detained.

If they’re willing to share personal information and their keys, she offers to let their family know if they’re detained, send another team to visit them in detention, connect them with a lawyer when available and move their vehicle so it doesn’t incur fines before their family can pick it up.

Masked federal agents wait outside an immigration courtroom on Tuesday, July 8, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Olga Fedorova)

Many people are in shock when judges dismiss their cases, Gutiérrez said. “It’s incomprehensible for many of them, who say, ‘I paid taxes. I already have an apartment. I have a car … why are they going to detain me?’”

At that point, Gutiérrez said, “There really is no escape. You have to pass, no matter what, by the immigration agents. So it’s like Jesus, who goes directly to the cross.”

The Rev. Chloe Breyer, an Episcopal priest and director of the Interfaith Center of New York, told RNS witnessing detentions was “harrowing.”

“ All I could do is get their name in this tiny millisecond between when they left the courtroom door and when they were picked up by these officers,” she said.

“ We’re witnessing a kind of public display of lawlessness,” Breyer added. She, like Gutiérrez, said there seemed to be no “rhyme or reason” behind which immigrants were detained and which were able to leave.

The Episcopal Diocese of New York has publicized that three of their parishioners have been detained in courthouse arrests and has held a training on court accompaniment for over 80 clergy, said Mary Rothwell Davis, the diocese’s vice-chancellor for immigration and refugees. On July 8, Bishop Matthew E. Heyd witnessed immigration court detentions.

The Rev. Fabián Arias, right, assists an immigrant family outside the Jacob K. Javits federal building, Thursday, July 17, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Breyer said she has gone to immigration court about half a dozen times in the last six months, along with rabbis and other Christian leaders. She has worked with the New Sanctuary Coalition, through which she shows up to accompany immigrants who happen to be there that day, and also with specific clients at the request of their lawyers.

In Los Angeles, Isaac Cuevas, director of immigration and public affairs for the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, has trained about 180 priests, deacons and religious sisters in court accompaniment. While they make an effort to match parishioners who request accompaniment for immigration court with someone who has gone through the program, the vowed religious largely create their own schedules for going to courts in the area.

“If people are in need, then we try to come forward and answer that call however possible,” said Cuevas, emphasizing that they do so not by civil disobedience, but through prayer, solidarity and recommendations to seek legal advice.

Another LA group, Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, observes courts daily.

In Arizona, Alicia Contreras, executive director of Corazón AZ, part of the grassroots multi-faith Faith in Action federation, said faith leaders in the state attend immigration court when community members request accompaniment. It is part of the group’s broader work, including know-your-rights and family defense planning, when a family makes plans for children, pets and bills in the event of a crisis. Corazón AZ has partnered with Puente, another Phoenix organizing group that maintains a more regular presence at the courthouse.

Corazón AZ has sent Disciples of Christ, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Catholics, Unitarian Universalists and volunteers without a specific tradition to the courthouse. The majority have been lay people.

“If I can offer a word of prayer, if I have brought folks a rosary or just sat with them, give them a gentle touch on their back, a hug when they need it, this goes a long way to calm the nerves,” Contreras said. She reminds immigrants to breathe. “We are not in control of a lot, but we are in control of our breathing.”

Fear can also cause immigrants to “black out” during their hearings, leaving them unable to remember what happened, Contreras said, explaining that faith leaders can help explain what happened afterward. In the worst cases, fear can lead community members to skip their court dates, a guaranteed way to enter deportation proceedings, she said.

Court accompaniment is an expression of faith, Contreras said.

“I know that their higher power, or in my faith tradition, God, does not want this for them,” said Contreras, a Catholic. “God is not putting the barriers, and God also is not wanting us to look away.”