(RNS) — The city of Jerusalem earlier this month froze the bank accounts of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, the church body that represents around half of all Palestinian Christians and is a major landholder in Israel.

According to an email from the Jerusalem municipality, “administrative enforcement proceedings were initiated against the Greek Patriarchate for failing to settle their property tax obligations on assets that are not used as houses of worship.

“This action was taken despite efforts to engage in dialogue with them and their disregard of the municipality’s formal notices demanding payment,” the city of Jerusalem stated.

During the freeze, the church cannot access funds, leaving it unable to pay employees and operate the schools, monasteries and charitable institutions it maintains.

The move represents the latest development in a long battle between the church and municipality over the church’s extensive landholdings. The Greek Orthodox Church is one of the largest landholders in Israel, controlling large swaths of land far beyond historic churches and religious institutions. The Knesset, Israel’s parliament, is built on land leased from the Orthodox Church.

According to the patriarchate, the church has always paid taxes on its commercial properties, but in 2018, the municipality demanded back taxes on charitable and religious properties not used strictly for prayer or religious teaching, totaling millions of shekels and breaking centuries of status quo. During a previous attempt to freeze the patriarchate’s accounts over the issue, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu intervened back in 2018 in favor of the churches, but under Israeli law, the matter ultimately rests with the city government.

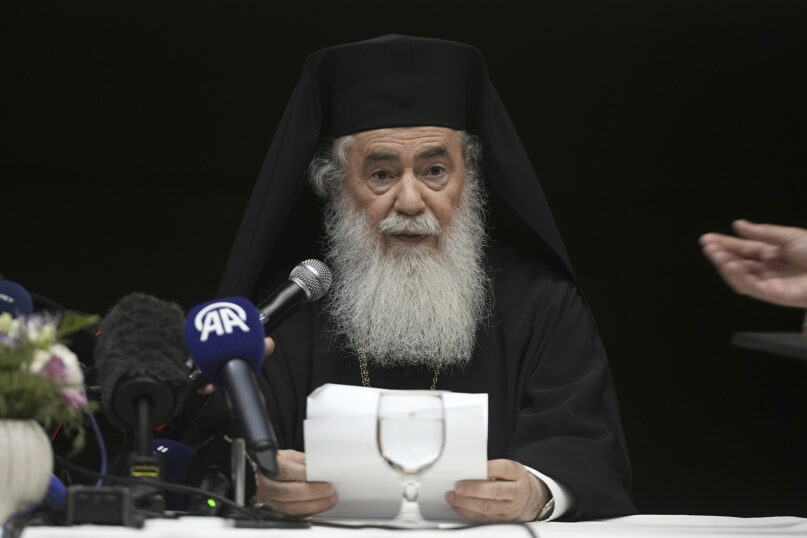

Greek Orthodox Patriarch Theophilos III speaks during a joint press conference with Latin Patriarch Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, not pictured, following their visit to the Gaza Strip in Jerusalem, Tuesday, July 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

Though it’s unclear how the church will regain access to its accounts, Christian organizations around the world have condemned the freeze.

“The church leaders argue that they have never paid municipal or governmental taxes during the periods of Ottoman, British, Jordanian, and Israeli rule,” advocacy group Protecting Holy Land Christians said in a statement. The organization, assembled by Theophilos III, patriarch of the Orthodox Church of Jerusalem, is co-chaired by Christian leaders, including Nourhan Manougian, Armenian patriarch of Jerusalem, and Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem. “(The church leaders) assert that as religious bodies, they fulfill vital roles by maintaining educational, welfare and charitable institutions that serve the local population, effectively acting as substitutes for the State in these areas. Therefore, the State should support them rather than impose taxes on them.”

The Armenian Patriarchate is also embroiled in a legal battle over properties in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The decision to freeze the church accounts comes as Christians face increasing challenges throughout the Holy Land amid the Israel-Hamas war and a surge in settler violence in the West Bank.

“As an Armenian living in the Old City, it is deeply troubling to witness the gradual erosion of our Christian presence here,” Levon Kalaydjian, an Armenian Christian activist in Jerusalem, told RNS. “These are not abstract concerns — every legal dispute, every case of intimidation and every act of hate crime chips away at the sense of belonging that generations of our families have cultivated in Jerusalem.”

FILE – A general view of a parking lot that is part of a contentious deal in the Armenian Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem, Tuesday, May 30, 2023. The 99-year lease of some 25% of Jerusalem’s Armenian Quarter has touched sensitive nerves in the Holy Land and sparked a controversy extending far beyond the Old City ramparts. (AP Photo/ Maya Alleruzzo)

Christian communities in Israel have also been the target of increasing attacks and harassment, according to the Jerusalem-based Rossing Center for Education and Dialogue, an organization that promotes religious and ethnic inclusivity. In 2024, 111 attacks on Christians were recorded in Israel, according to a report by the Rossing Center, compared to 89 incidents recorded the previous year. Forty-six of the 2024 incidents were physical attacks, such as pepper spraying, spitting and hitting, and 47 targeted clergy, including priests, monks and nuns, who are easily identified by their religious dress.

According to the report, the majority of attacks were perpetrated by Jews affiliated with Israel’s ultra-Orthodox and National Religious movements, the latter of which is the main driver behind the settlement movement.

Earlier this month, Israeli settlers encroached on the lands of a Greek Orthodox monastery in the West Bank city of Jericho, sparking concern from officials in Athens and building diplomatic tensions between Greece and Israel, Greek media reported.

The Greek Constitution considers the Greek Orthodox Church — of which the Jerusalem patriarchate is an arm — to be the prevailing religion of the Greek state, and the protection of monasteries like the one in Jericho, or the monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai in Egypt, falls under the purview of Greece’s foreign ministry.

Last month, attacks by Israeli settlers on the Palestinian Christian-majority village of Taybeh in the West Bank were also condemned by church leaders.

Char marks, which Palestinians say are from an attack by Israeli settlers, are visible in the cemetery near the St. George Greek Orthodox Church in the West Bank village of Taybeh, July 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

“The Council of Patriarchs and Heads of Churches calls for these radicals to be held accountable by the Israeli authorities, who facilitate and enable their presence around Taybeh,” read a joint statement by Theophilos and Pizzaballa. “We call for an immediate and transparent investigation into why the Israeli police did not respond to emergency calls from the local community and why these abhorrent actions continue to go unpunished.”

The attacks, which resulted in the burning of a fifth-century church, also received a rare condemnation by American Republican and evangelical leaders who have traditionally supported the Israeli right.

“What’s happening in the West Bank bothers the hell out of me,” United States Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-South Carolina, said in an interview with Fox News. “I want to find out who did it, and I want them to be punished. … And if it was settlers from the West Bank, Israelis, I want them to be punished.”

Mike Huckabee, U.S. ambassador to Israel under the Trump administration, visited the town after the attack.

“… We will certainly insist that those who carry out acts of terror and violence in Taybeh — or anywhere — be found and be prosecuted. Not just reprimanded, that’s not enough,” Huckabee said in a July 19 statement. “People need to pay a price for doing something that destroys that which belongs, not just to other people, but that which belongs to God. That is a sacrilege. It’s against the Holy.”

The overwhelming majority of Jerusalem’s Christians are East Jerusalem Arabs. They receive neither the full rights afforded to citizens of Israel nor the Palestinian Authority.

In 1980, Israel formalized its annexation of the parts of East Jerusalem it conquered in the 1967 Six-Day War, claiming a large swath of the West Bank up to the suburbs of Ramallah and Bethlehem, but made little effort to adopt its people. When the Oslo Accords established the Palestinian Authority 1993, East Jerusalem and its people were outside the lands it was slated to control and thus not under its purview.

Instead, nearly 400,000 East Jerusalem Arabs have the status of permanent residents in Israel. They have the right to vote in local municipal elections but not national ones, and can have their residency and right to return to Jerusalem revoked if they move outside the city for too long.

“The wider Christian community feels increasingly vulnerable, as if our very existence in this city is being questioned,” Kalaydjian said. “Our continuity, our traditions and our connection to Jerusalem are at stake.

“What makes this especially painful is that Jerusalem has always been a mosaic of faiths and histories, yet today, we feel our place in that mosaic shrinking. It is not just about buildings or land — it is about culture, identity and the very heartbeat of a community that has survived centuries,” he said.