(RNS) — In May of 2022, in the middle of her master’s degree at Harvard Divinity School, Ariella Gayotto Hohl lost her father to cancer. Five thousand miles away from her home in Brazil, she never knew how sick he was or got to say goodbye.

Overwhelmed by grief and feeling that her Muslim faith had been shaken, Gayotto Hohl met the team members at Unity Productions Foundation shortly after her father’s death and found that they were exploring some of the same questions about Islam and loss. By the beginning of 2023, she was working with them to film a documentary about five stories of love in Islam.

In “Islam’s Greatest Stories of Love,” Gayotto Hohl speaks with experts and travels to new locations to better understand the wisdom in five stories of various types of love: star-crossed lovers Layla and Majnun; Shah Jahan and his love for Mumtaz preserved in the Taj Mahal; the Prophet Muhammad and his first wife, Khadija; Malcolm X and his half-sister Ella; and the profoundly spiritual friendship between Rumi and Shams.

Omid Safi, a professor studying Islamic mysticism at Duke University, tells Gayotto Hohl of Rumi’s wisdom, “Every heart breaks, and your heart must break. But what a difference there is between a heart that merely breaks and a heart that breaks open,” allowing one “to see love in everyone and everything.”

The film will premiere on PBS on Friday (Aug. 22) and will be available on PBS’ website and YouTube for a month without a paywall.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

A behind-the-scenes view as Ariella Gayotto Hohl, left, records an interview in the documentary “Islam’s Greatest Stories of Love.” (Image courtesy of PBS & Unity Productions Foundation)

You start the film in a spiritual crisis after the death of your father. Did you find peace or clarity in making the film?

One of the takeaways I got from making the film, from having all those conversations, is actually what ended up being one of the taglines in the movie, which is love is more than an emotion; it’s a force.

And for me, that whole concept has been really transformative, to be able to realize that love is what allows us to do things that otherwise we wouldn’t be able to. So in the film, you have all of these beautiful stories, like the story of the prophet and Khadija, his first wife — if she hadn’t believed in him and loved him, I don’t know what Islam would’ve looked like today, or if Islam would’ve existed.

Love is a value and a choice. It’s not necessarily something we are born innately with. You know, it’s something that we get to choose every day. Talking for example to associates of Malcolm X, it’s really obvious in the way his sister showed up for him. That for me was really healing.

For grief specifically, having a chance to talk to people and see that love outlasts us all — that even when we feel like we’ve lost something — it’s still something that lives within us, that inspires us. Like the fact that I got to make a movie about the love that my dad had for me and I had for him, and how that’s been a way to give to other people who reached out to me after the premiere, it really strengthened my faith because it allowed me to see a little bit of the bigger picture.

Poster for “Islam’s Greatest Stories of Love.” (Image courtesy of PBS & Unity Productions Foundation)

That idea of love outlasting life has given me a lot of meaning and allowed me to do something with that crisis and that pain. It was (my dad’s) love that gave me strength and power to be able to do this because it was a very vulnerable project.

Can you tell me about your conversion to Islam?

I was raised Catholic, like the majority of Brazilians. And when I was preparing for my First Communion, my mom was converting to Judaism, so I did my First Communion, but then from that moment onward, I was raised Jewish.

I was a teenager who was trying to belong and try to prove to myself that I fit in, which is the case for any teenager in any situation. But in this particular case, I was really trying to prove myself as a part of the Jewish community, so I started becoming involved in every aspect of community life. I learned Hebrew. I started leading prayers at the synagogue. I joined the youth group and was teaching kids on the weekends. I had a pretty strict observance of the Sabbath, and I only ate kosher meat.

I was immersed at that point in my life, but somehow there was always something I felt was missing. I felt the need to prove I belong, but it meant I also had to block some of those connections that I had to figures that were really important in my upbringing, and they were everywhere in my grandparents’ home, like Jesus, like Mary. So that was always a little difficult.

It was in Bethlehem that everything changed. I was spending some time there during college. I was living on Star Street, which leads to the Church of Nativity, which was mind-blowing at the time. Because Bethlehem is such a central place for the intersection of Abrahamic faith, it was the first time I saw these communities interact for the first time.

It was also the first time I learned that Islam embraced both Jewish Scripture and Christian Scripture. The more I studied the more I felt whole in the Islamic tradition, like I didn’t have to choose. I found this balance in Islam that allowed me to be my full self in ways I don’t think I had been able to before.

What do you hope viewers take away from “Islam’s Greatest Stories of Love”?

Humans have tried to understand the meaning of love forever, and Islam is no exception to that. It’s not something that’s necessarily unique to Islam, but unfortunately it’s not something we hear a lot— of Islam being associated with love specifically.

What I want people to get out of the movie is that this happens to be situated in a Muslim context because I’m a Muslim woman and these stories are coming from the tradition I’m part of. But these stories are universal. It’s someone who is going through loss and is trying to understand that. These are universal questions.

So the idea isn’t necessarily to think this is something unique to Islam specifically. Pay attention to how these things function in Islam but understand these are actually things we go through as humanity as a whole.

These are some of the most well-known stories in Islam. What was familiar to you and what was new about the process of diving into them?

All of the stories to some extent are very familiar because they’re part of Muslim culture in general, but almost all of them had a very novel way they were being understood and looked at (in the film).

The prophet and his wife are obviously very central in Muslim faith. But a lot of people came up to me (at the premiere), saying, “Wow, I’ve never looked at this from a human love story.”

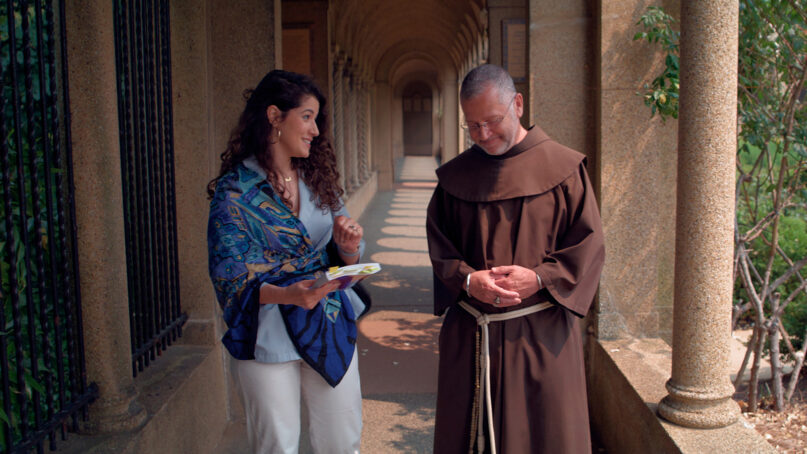

Ariella Gayotto Hohl, left, speaks with the Rev. Michael Calabria in a still from “Islam’s Greatest Stories of Love.” (Image courtesy of PBS & Unity Productions Foundation)

To look at it from a human perspective and understand what he was going through as a father, as a husband, and see what that love meant that they shared and how it was able to nurture him into the prophet he became was really cool and inspiring in my own life too.

The Taj Mahal was very different. Father (Michael) Calabria, who is one of the most amazing people I’ve ever met, a Franciscan friar and an Islamic studies professor, had this very particular vision of the Taj Mahal as a sacred text, as a way of atonement for Shah Jahan.

In the film, you mention that many friends and even some family turned their back on you when you converted. How do you think this film might impact people with preconceived notions about Islam?

Centering on love and on the personal is a very powerful way to show rather than to just try to convince someone that love is such a powerful force of Islam.

When I converted, a lot of people didn’t understand, and even my dad was a little silent for a while. But then I was fighting an infection and I was trying to fast during Ramadan, and it wasn’t pretty. My father was really concerned. This was like two weeks before he passed. He researched within Islam about the rules of fasting, and he told me that he looked into it, that it was OK for me not to fast and that God would understand.

And it’s actually the last voice note I have from my Dad. Brazilians, Latinos in general, love their WhatsApp voice notes. The driving force there was the love my dad had for me, and that’s what drove him to understand from my lens why this was important. He didn’t tell me “This is stupid, don’t do it,” but he was able to put himself in my shoes and try to see things from my perspective because he loved me.

We’re not trying to convince anyone that love and Islam are completely intertwined. We’re inviting people to see that on their own through personal stories, through these stories that have inspired people through millennia. When you’re telling it from a very personal perspective, that allows us to connect in ways that don’t feel combative.