(RNS) — Two Orthodox Christian women have created a new website about sexual misconduct and abuse in their denomination that not only names names, but offers victims help in coming to terms with their trauma.

More than two years after Katherine Archer and Hermina Nedelescu decided more needed to be done to advocate for clergy abuse survivors, the two recently debuted Prosopon Healing as a way to call attention to the problem. “Katherine and I were determined not to be silenced,” said Nedelescu. “The Orthodox Church has a clergy sex abuse problem it must reckon with.”

But the two founders — one a therapist-in-training, the other a neuroscientist — also present evidence-based research and supportive resources rooted in behavioral neuroscience to explain the actions of the predator and the victim. Its database collates third-party information across the internet on documented and alleged Orthodox clergy abuse.

The Prosopon site draws heavily on work by Melanie Sakoda and Cappy Larson, who for decades collected information for their now-retired Orthodox abuse website, Pokrov.org. “The reason Katherine and I did this in a year and a half and completed it in two years is because of Melanie and Cappy,” Nedelescu said. “Melanie gave us the list. We ourselves also did a thorough search, but many of the names are coming from Melanie’s work.”

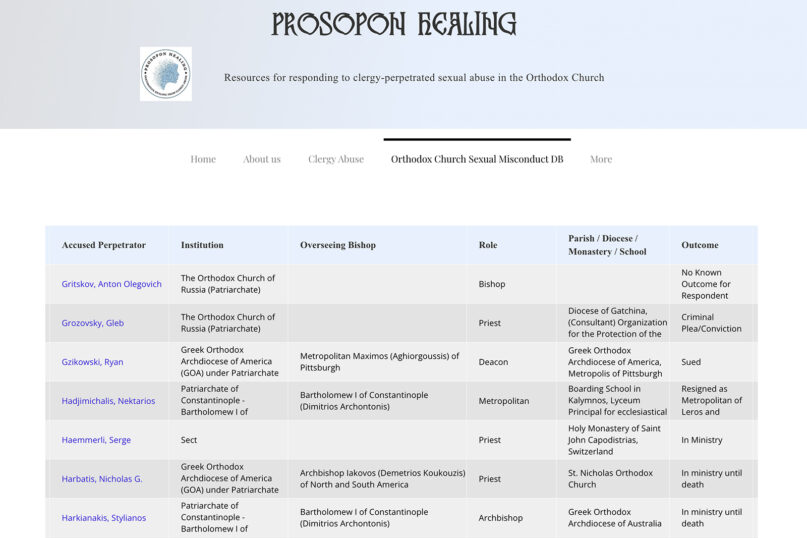

The new database adds an extra layer to account for multiple levels of authority. For each alleged or charged abuser, the list adds the overseeing bishop whom the abuser ultimately reports to.

A page of the Prosopon Healing Orthodox Church Sexual Misconduct Database. (Screen grab)

One of those overseeing bishops, according to the site, is Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople, who is visiting the U.S. and on Wednesday (Sept. 24) received the Templeton Prize, given for integrating Christian theology with environmental care. The first among equals among Orthodox patriarchs, Bartholomew is known as the “Green Patriarch” for being the first religious leader to call destruction against the environment sin. But he is also known for his silence on clergy sexual abuse.

Bartholomew appears in the database as the overseeing bishop of 50 abuse incidents out of 266 compiled thus far, gleaned from public media reports and other documents.

Archer, 41, who is earning a master’s degree in theology while training as a therapist, has felt this silence personally. After suffering abuse, she has reached out to parishioners and church leaders for years to hold her abuser accountable and to receive healing. She has been told she is “going to hell” or is a “mentally ill sex addict,” she said, and was counseled to remain silent and shamed into feeling responsible for her abuse.

Archer said she doesn’t say the site has all the answers — “survivors are experts in their own experiences,” she said — “I just want to offer the support to somebody that I didn’t receive.”

The word prosopon — the Greek word for “face” — was chosen for the site’s title to foster the idea that healing comes “by looking at each other’s faces, within community,” Archer said. “I felt that I had been shunned and unable to show my face. In fact, my first response to my priest (who abused me) confessing his ‘feelings’ (for me) had been to bury my face.”

Hermina Nedelescu, left, and Katherine Archer at the California State Capitol in Sacramento. (Courtesy photo)

The Romanian-born Nedelescu, 45, a theologian as well as a neuroscientist, documents on the site how individuals who suffer from sexual predation and being sexually assaulted need medical treatment. The experience of abuse, she said, can lead to drug misuse, eating disorders and cardiac disorders as coping mechanisms.

“Focusing on therapeutic strategies is most important for humanity since both predators and victims belong to the same species,” Nedelescu said. “There is only one humanity.”

Archer, who was raised in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints before being received into the Orthodox Church at age 18, presents therapeutic goals on the website, applying not only her graduate work in counseling and theology but also training in nonviolent communication and harm reduction.

“I would venture to say that most therapists are not trained to understand the trauma of sexual abuse within a religious context,” Archer said, adding that Orthodox clergy also usually see clergy sexual abuse only through a spiritual lens.

These misunderstandings add on layers of trauma to any incident of abuse, in addition to the victim’s own failure to understand just what has happened. As a result, victims suffer extreme isolation and even suicide. “So, getting this right is truly a matter of life and death,” said Archer.

Jovana Trninic, who was abused as an adult, said Prosopon gave her the language to understand she was not responsible for what she experienced. The website also helped her understand the mechanics behind her abuse and why she reacted the way she did.

“When I read through the website, I said, ‘Oh my God, this makes sense,’” said Trninic, who returned to Orthodoxy a few years ago. “I saw how the priest was basically grooming me. I didn’t even know the word grooming. And this is how I understood, ‘Oh, they’re using all these tactics.’”

Trninic said she still believes in God, but remains confused as she continues to process what happened to her. “They broke my trust, the institution and everything, because all these people who told me, who introduced me (to) the practice and how to do it the right way,” she said. “I was doing everything the right way, and because I was doing it the right way, I got abused.”

Broken trust can harm one’s ability “to receive the love that God gives us” because the abuser is a representative of God, said Aristotle Papanikolaou, a Fordham University professor of theology and co-founding director of the school’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center. “Trauma does affect one’s relationship with God,” he said. “If, in fact, we are called to love, love God and love neighbor, that kind of abuse and that kind of trauma strikes at the core of what it means to be a Christian.”

Papanikolaou said the Orthodox Church needs to stop presenting a facade of perfection and admit it makes mistakes. He said predators seek out institutions that protect the institution’s image more than the victim, believing it will cover for their violence. The church, he said, “needs to send a message that you cannot get away with that here. ‘We will make you accountable. There will be transparency, and you will be prosecuted. And we will be a spiritual resource for the victims.’ But the church hasn’t done that yet.”

Instead, according to Amos Guiora, a University of Utah professor who studies institutional complicity in sexual abuse and advises Archer and Nedelescu, the Orthodox Church and similar institutions rely on a network of enablers.

Orthodox abuse survivors and advocates have recently become more vocal. In a Sept. 15 media press release about the ecumenical patriarch’s Templeton Prize, they explain how Bartholomew enables abuse through his silence, with some asking the prize’s sponsor, the John Templeton Foundation, to withdraw the honor.

In the last six months, a team of advocates, including Archer, Nedelescu and Sakoda, has sent letters to the foundation asking them to acknowledge the clergy sexual abuse survivors Bartholomew has remained silent about. They propose giving to organizations that are working with the survivors the same amount of money that comes with the prize. The letter also suggested the patriarch and the foundation publicly acknowledge the alleged and charged Orthodox clergy abuse, as was done with past controversial recipients like Jean Vanier and Francisco Ayala.

“I believe awarding the Templeton Prize to a leader who has failed to speak out on this crucial issue was extremely short-sighted of the Foundation,” Sakoda said in the press release. “To me, it calls into question Templeton’s moral credibility when it ignores the plight of victims who are still waiting to receive both help and justice.”

One of the letter writers is a former Orthodox priest, Bojan Jovanovic, who described witnessing severe abuse in the church, including child sexual abuse and even the murder of a previously assaulted child. These experiences led him to leave the priesthood and focus on advocacy.

They have yet to receive any response from the foundation.