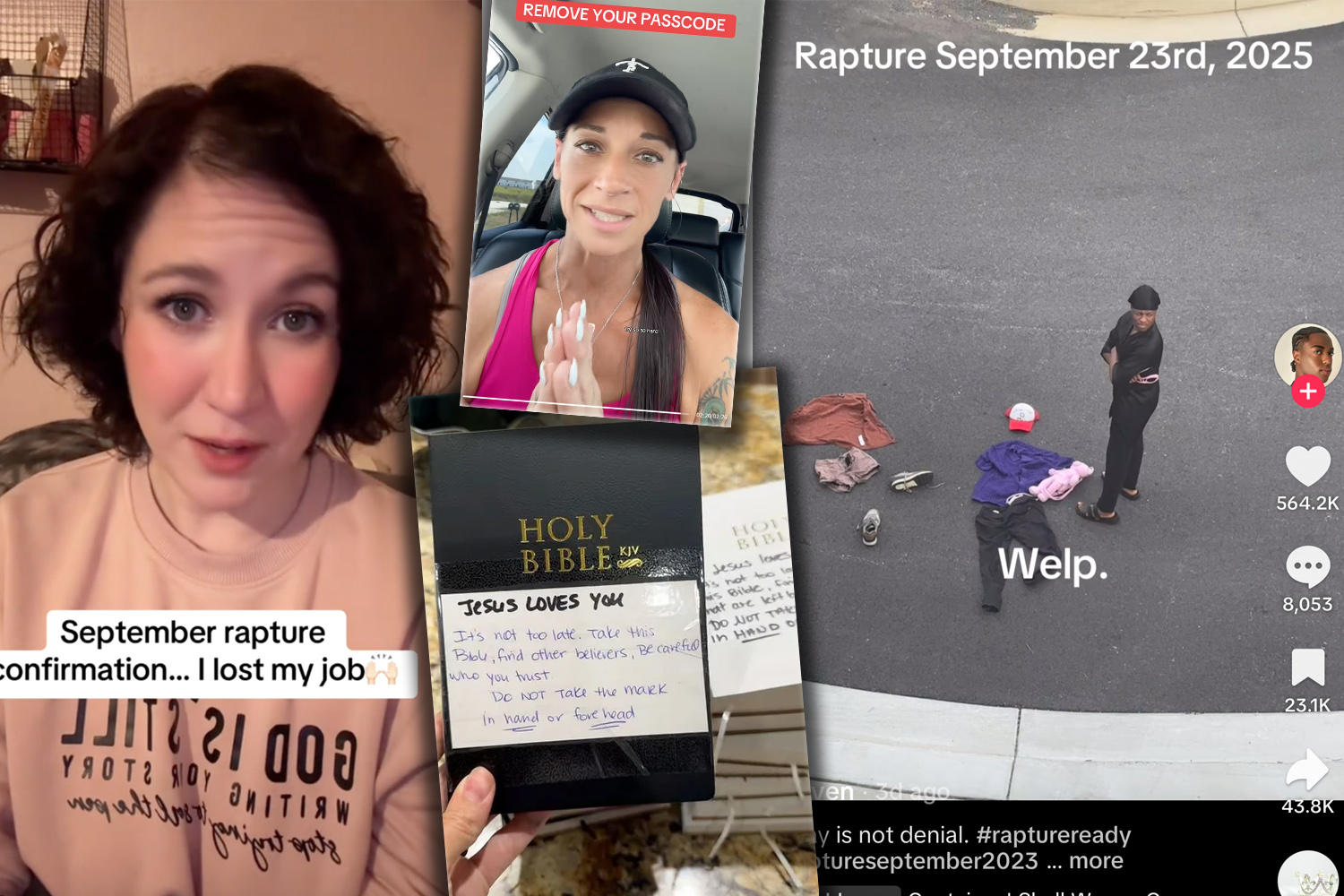

(RNS) — Hannah Gallman announced on TikTok that she was fired from her job on Monday (Sept. 21), shortly after praying to God to allow her to be home with her family during the rapture, a biblical event she believed would occur this week. As her prayers were seemingly answered, her more than nine-minute TikTok video drew 1.2 million views under the hashtag #RaptureTok.

“I’m pretty much not even reading comments anymore, the majority are negative,” Gallman, who lives in Louisiana, wrote in a message. “It’s sad to see so much arguing and mocking in the comment section.”

Not long after, her video resurfaced on Rapture Clownery Archive 2025, a TikTok account created three days ago by a Canadian user named Evren to preserve content considered #RaptureTok. The hashtag went viral, with the most views on accounts reenacting and mocking posts about the rapture that some Christians believed was imminent. The Rapture Clownery Archive 2025 has 11,000 followers and more than 54,000 likes since Monday. Several of the account’s early reposts collectively saw more than 1.5 million views.

“If it was one person going through a manic episode, then I wouldn’t bother, but these people are creating mass fear and saying things that are interrupting people’s lives,” Evren, who asked to be identified by his first name only for safety concerns, wrote in a message. “I didn’t want to let them have the ability to deny the things they said and did.”

One TikTok user commented on the video Evren republished of Gallman, “Why do these people think they’re so special that God is telling them something that NO ONE KNOWS THE DAY OR THE HOUR OF.” Comments under Gallman’s original video read, “If the rapture doesn’t happen can yall still leave” and “please consider doing some research on religious psychosis.” Very few comments seemed to support Gallman’s faith, but many claimed to worry about her mental health. “Oh man, I thought this was satire bc I’ve only been getting the satire ones on my fyp (social media feed),” one user wrote.

RaptureTok is the latest example of how TikTok amplifies the often strangest and most extreme corners of religion — typically through re-posts where users mock or comment on others’ religious performances. And as another viral Christian trend makes national news, some worry about the platform’s influence on the minds and faith of young people.

(Photo by Solen Feyissa/Unsplash/Creative Commons)

TikTok rewards content that provokes, often through mockery or spectacle, because it captures and keeps people’s attention. According to recent data from a popular SEO analysis website, TikTok has about 170 million accounts in the United States — almost half the number of people living in the country. American adult users spend an average of 52 minutes a day on the app. The platform skews younger, with TikTok especially popular among Generation Z and younger millennials, according to a fact-sheet compiled by April ABA.

Franziska Roesner, a computer science professor at the University of Washington in Seattle who studies TikTok’s algorithm, told UW News in 2024 that the platform doesn’t just show users what they follow but predicts what might grab their attention, sometimes funneling them into “rabbit holes” of provocative material.

“Platform designs are not neutral, and they influence how long you watch and what you watch, and what you’re getting angry or concerned about,” Roesner said, according to the story. “It’s very difficult to explain exactly why a particular video was recommended … TikTok is more of a black box.”

Earlier this year, another “ChristianTok” trend went viral when a handful of women posted videos of themselves pouring grape juice around their homes as a symbol of Christ’s blood to ward off spiritual danger. The practice might have been obscure, but it was amplified after “WitchTok” creators, who post about witchcraft, mocked it as little more than spell work.

RELATED: Rapture, again: Why the end times never end

The accusation sparked a flood of cross-community commentary. Many of the videos were also republished on “DeconstructionTok,” a subgroup of TikTok that functions much like sub-threads on Reddit and aims to “deconstruct” various beliefs, ideologies and expressions of Christianity.

Heidi Campbell. (Photo courtesy of Texas A&M University)

Heidi Campbell, director of the Network for New Media, Religion and Digital Culture Studies at Texas A&M University in College Station, said that since 2016, online discourse has shifted toward what she calls a “performance of meanness.”

“The screen has allowed us to broadcast so much more diversity, which can be a positive thing,” Campbell said. “But instead of bringing us closer together, which a lot of internet prophets and cyber philosophers kind of said in the 1990s, it’s actually brought more division.”

People performing religion through TikTok content, in particular, is a hotbed for accusations, prejudice and even misinformation, Campbell said — especially among young people, who increasingly identify as having no religion.

“Now, we have these technologies that take those private conversations from those communities and make them public,” Campbell said. “In some ways, they’re decontextualized. People are seeing 30 seconds or a minute of a kind of a narrative that if you know the insider language of that community, it makes sense. If you don’t, it makes no sense.”

Videos of cycling instructors urging women on stationary bikes to “breathe in the Holy Spirit,” memes of “Christian girl autumn,” clips of President Donald Trump speaking about the Bible, and even AI-generated images — like ones depicting Jesus hugging children displaced by the catastrophic flooding in Texas this summer — have all fueled debate on TikTok. The content often draws so much attention that it spreads to Instagram, Facebook and YouTube, and even gets covered by major news outlets.

Britt Hartley, an ex-Mormon, religion scholar, deconstruction coach and popular TikTok creator, has been posting since 2022. With nearly 712,000 followers, her account, NononsenseSpirituality, has become a leading voice in the deconstruction community, often tagged in videos for her commentary.

“TikTok is addicting because you get a place to express your rage, disappointment, religious trauma and all the stupid things that religion does,” Hartley, an Idaho resident, said. “It’s kind of intoxicating in a way because it’s kind of a righteous anger, and it’s a cause.”

RELATED: Gen Z’s nones have their own beliefs. Try working with them, not converting them.

Evren, who grew up Mormon, said he relates to those posting out of religious fear. Still, he emphasized that his main goal is to create an archive.

“I do think that many are being genuine, that they are posting because they are scared. And they’re trying to ‘save’ people,” Evren wrote. “But I do think there are satire accounts or rage baiting accounts that are using this to gain views. Hell, some might argue that’s what my account seems like. But I prefer to think of my account as an archive.”

He described the ultimate goal for his page: “I want to see what their reactions are when their prophecy doesn’t come to pass,” he wrote. “For me personally, that part is more of a scientific curiosity into the psychology behind it. What will a person do when their prophecy that they relied so strongly on fails?”

From her vantage point, Hartley said she worries all the attention on breaking down people’s beliefs means TikTok users, especially young people, aren’t being encouraged to build community in its place. She said she believes there are lessons to learn from religion.

“There’s a baby in the bath water,” she said. “Especially for Gen Z to be on TikTok, deconstructing gender, religion, capitalism, they’re just deconstructing everything all the time. Then they’re in this massive meaning and identity crisis, and have massive depression and anxiety. They have no sense of how to build a self and a life.”

If the rapture doesn’t happen this week, Gallman said her faith will not be shaken. “My faith is in Jesus and not in a date, again, nothing changes for me,” she said. Despite the negative comments on her most recent posts, which are the only videos on her channel that touch on her faith, she said she won’t feel embarrassed about posting online.

“If you knew that something major was coming and a lot of people would suffer, and you had the chance of saving a few people by warning them … it would be wrong not to speak up just because you’re afraid of being called crazy,” she said.